Lichens

There are many rare and exotic species of Plants, Lichens and Bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), which call the British isles home and they all have their charms and important roles to play in our ecology, for me one of the the most interesting families has to be the Lichens.

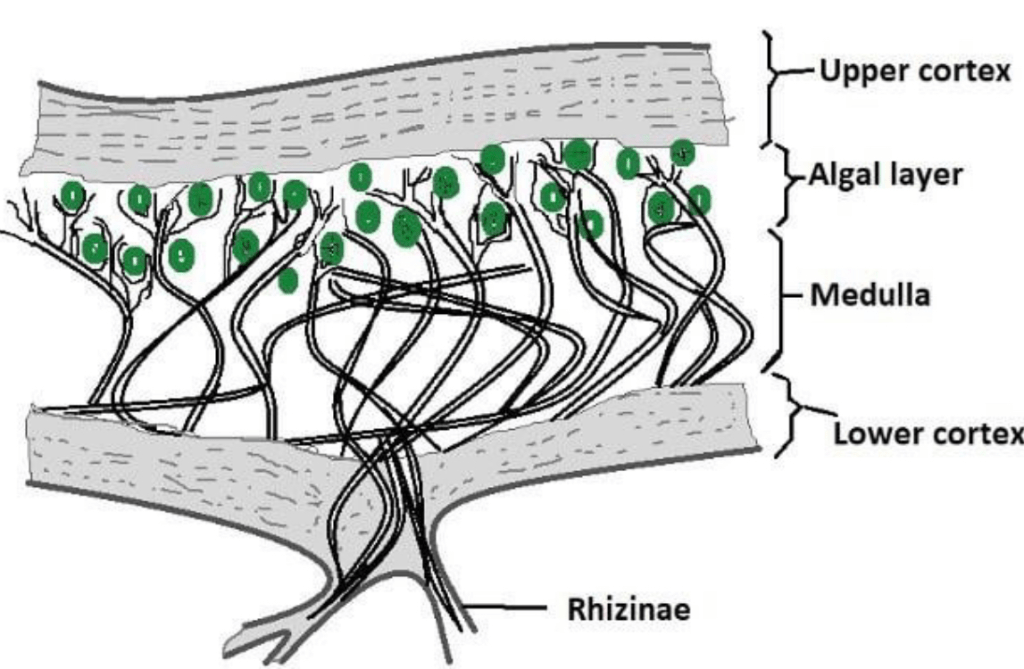

Lichens are not what you might call normal, ‘run of the mill’, plants, technically they are not plants at all but rather a combination of two organisms; algae, or sometimes cyanobacteria, and funghi, which have joined forces, collaborated and worked out their own, unique, way of going about the whole ‘life’ thing.

Mutualism

This kind of relationship is known by science as ‘mutualism’, as both organisms mutually benefit from the arrangement, and it is an essential survival technique for many species and eco-systems. In the case of Lichens the fungi provide the shelter, or structure, and the algae or Cyanobacteria photosynthesise, providing essential plant sugars, or energy basically, from the sun, this arrangement has worked out quite well too, as Lichens have been around for 400 odd million years now!

Indicative of clean air

Lichens have no roots as such and absorb nutrients and water from the air, which is why they do so well in moist climates, but this makes them very susceptible to atmospheric pollution. Indeed a fascinating fact about Lichens, (one of many!) is that they will readily absorb SO2, Sulphur Dioxide, a form of air pollution, from the atmosphere, however they do have a limit as to how much pollution they can tolerate and once this exceeds their capacity, they simply can’t survive any longer.

This handy fact means that the abundance of Lichen in an area can be measured, and this data used to gauge the local air quality, with a correlation between both the species of Lichen present and the air quality of the area also being a highly effective method, there is a simple scale which demonstrates this and also introduces you to the basic families of Lichens too:

Zero Lichen coverage

If a given area, let’s say a square metre, of a surface is measured and no Lichen is present, this means air pollution in that area is very heavy, think city centres and land downwind of heavy industrial plants for example.

Pleurococcus

Pleurococcus is a single-celled algae and not strictly a Lichen, it is used in some air pollution scales though, it appears as a light green dusting on surfaces which aren’t too exposed to the sun, it can tolerate quite a lot of pollution.

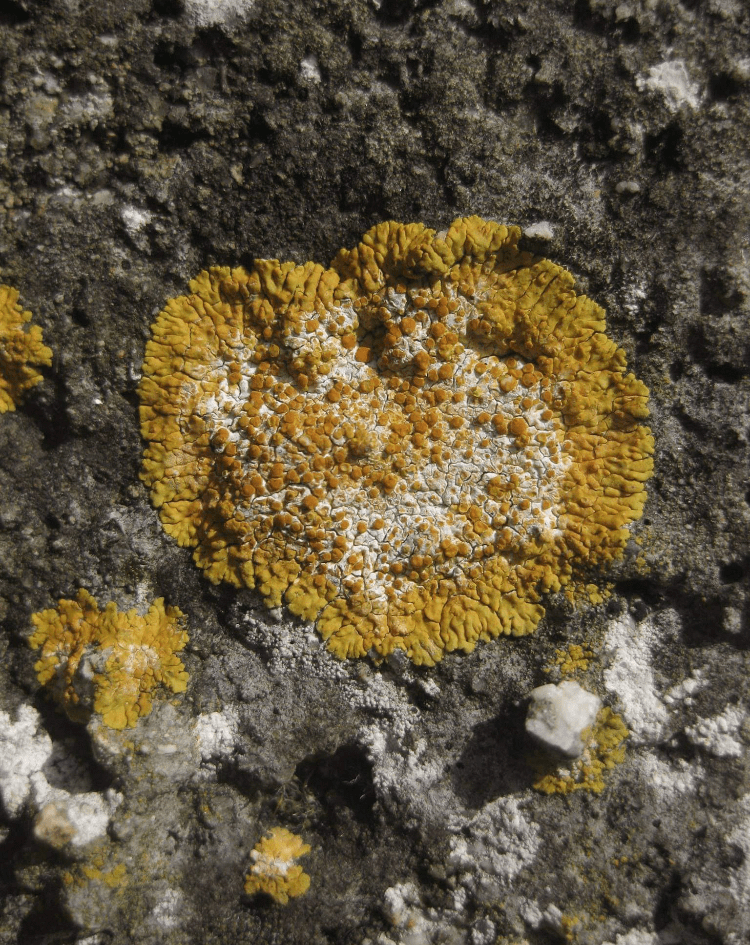

Crustose Lichens

These are flattish Lichens, which tend to form a ‘crust’ over surfaces, such as Caloplaca flavescens , a common Lichen often found on calcareous (limestone) rocks, walls and gravestones, these Lichens can tolerate a degree of pollution, mainly because they grow flat against, almost within, the surface of the rock.

Foliose

These are lichens such as Parmelia saxilitis and Xanthoria parietina, they have more ‘foliage’, or structure, to them than crustose Lichens, hence the name for their group, which means ‘foliage’. They can be quite leafy and full of convolutions and ridges, this gives them more surface area with which to absorb nutrients and moisture, but it also means that they absorb more air pollution, so, with some exceptions like Xanthoria parietina, they are further along the Lichen/air pollution scale.

Fruticose

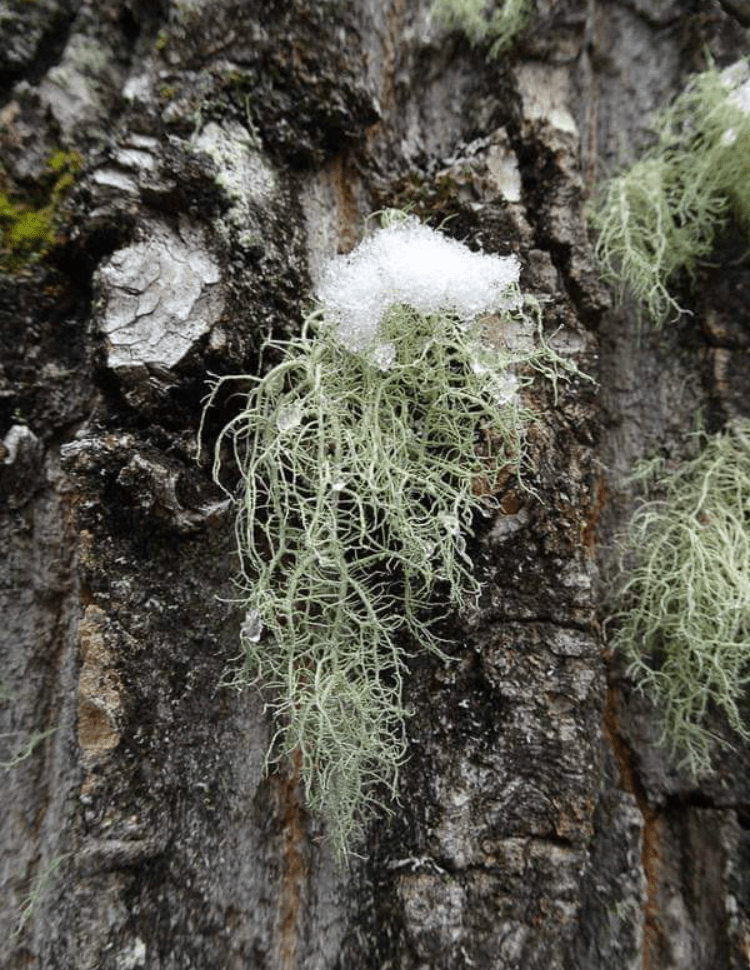

Fruticose Lichens, such as ‘Old Man’s Beard’, a common name for various, similar looking, members of the Usnea family, forms very bushy growths, with lots of ‘branches’, which give this type of Lichen its name ‘fruticose’. They are very hardy and can withstand being dried out, frozen and wind-blasted for periods of time, which means they are found in places no other organism can survive, even on the Antarctic continent!

However they are not very hardy when it comes to air pollution, epiphytic fruticose lichens, which grow on trees, (the Spanish moss you might see draped from trees in films based in the Deep South of America is a type of this) are the most intolerant of all Lichens to air pollution and in regions of the world where they are a main food source for animals, such as the Arctic where they keep Reindeer and Moose going through the long winters, any large scale die-off due to air pollution can mean a near collapse of the local ecosystem.

Rich palette

Lichens and Bryophytes really come into their own in our remaining bits of Temperate, or ‘Atlantic’ Rainforest, which are rarer now than their tropical counterparts, where they envelop the trunks and branches of the trees as well as covering most of the ground and bare rock with a multitude of wonderful hues and textures, without which our landscape would look vastly dull and drab. It is these so-called lower plants that give the Temperate rainforests their rich colour palette too and maybe we should recognise and appreciate them more for this.

A B-H

3 thoughts on “Lichens, and how they can be used to measure air pollution”