The Great spotted woodpecker, Dendrocopus major, dendrocopus being Latin for ‘tree striker’, is the most frequently seen of the four species of woodpecker native to the British isles. It is rapidly becoming the most common too as it’s range has spread to areas it was previously rare, including Scotland and Ireland, where they became absent in the past due to extensive deforestation, although this expansion in range is predicted to slow down once they reach western regions like Donegal, the Burren and the Hebrides, which are inhospitable to tree growth.

Striking appearance

It is a very striking bird in appearance with pied black and white plumage and a bright red vent (polite anatomical term for backside!), the adult males and females look similar but can be distinguished by looking at the back of their neck, where the male will have an obvious red spot, this is absent on the female and on younger woodpeckers.

Their favoured habitat is in mature deciduous woodland and over the years, as they have become more tolerant of humans, they have begun to move into urban parks and gardens too, even learning about the bonanza that can found by an enterprising woodpecker at the bird table!

The increase in Great spotted woodpeckers has been observed to have a negative impact on other species including its more diminutive relative the Lesser spotted woodpecker, Dendrocopos minor, whose nests it will raid and with which, as they favour the same habitat, it competes for food. A decrease in the breeding success of Marsh and Willow tits has been recorded in areas the Great spotted woodpecker has moved into, also thought to be down to nest raiding.

Striking sound

Both the female and male Great spotted woodpecker drum, with the highly territorial male doing so to defend his territory, usually around 10 to 15 acres in size, and attract a female, once paired up the female will also drum in order to maintain contact with the male. Drumming starts in February and continues through to around June/July and the male will utilise anything that has the right acoustic properties, they have even been known to drum on steel poles and lamposts!

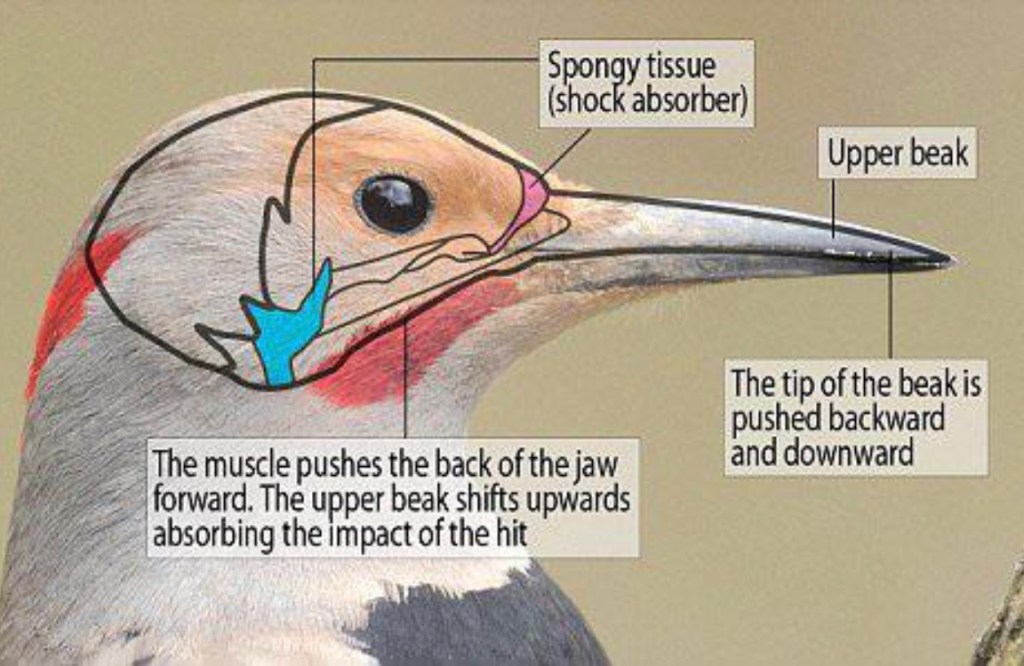

A male Great spotted has been counted drumming up to 600 times a day, at a rate of 10 to 40 strikes a second, and they can only do this without knocking themselves senseless because they have a sort of shock absorber at the base of their beak, as can be seen in the image below. The frequency of strikes, rather than the strength of impact, (although they do strike with a force of up to 100g!), is the reason their drumming can be heard for a long distance away, as they create a resonating effect which amplifies the sound to greater effect.

A woodpecker’s beak is not only used as a percussive instrument but also as a chisel with which to excavate nest holes, and each year a pair will create a new nest, usually, but not always, in dead wood. This house building takes from 2 to 4 weeks and in the nest the female will lay a clutch of 4 to 6 white eggs, with both the male and female will taking turns to incubate the eggs which hatch after about 12 days. The young woodpeckers fledge at around 20 to 24 days old and stick around with their parents for a further 2 to 3 weeks learning the facts of life, such as how to hunt for food.

Omnivorous predators

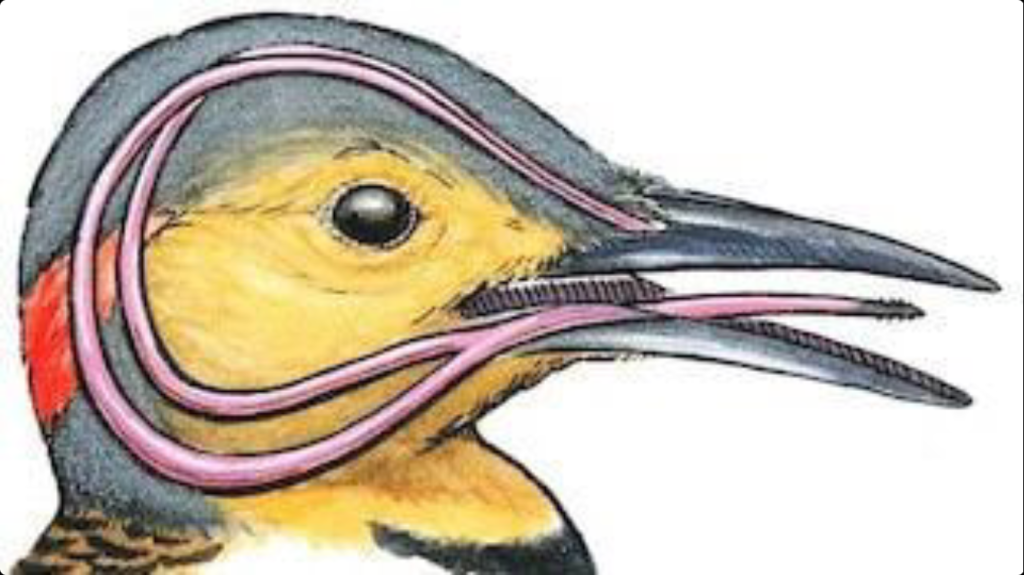

Like all woodpeckers the Great spotted has evolved to hunt for grubs and insects in and on trees, their tongue is much longer than their skull, in fact it runs around the back of their brain and is anchored at the base of their nostrils, a microscope reveals that this tongue is covered in tiny barbs, which latch onto the unlucky grub or insect.

The Great spotted woodpecker hunts in a meticulous manner, working it’s way up a tree trunk or branch and moving from side to side in order to cover more surface area, as it goes it carefully taps and listens for any tasty grubs hidden in the wood beneath and makes sure to prise off any loose bark in order to inspect the underneath for insects. They tend to hop rather than climb and if they are disturbed will travel around to the other side of the tree to hide, if you follow them they may continue moving around the trunk or fly off, issuing a harsh, peeved sounding alarm call.

As well as insects they will forage for acorns, nuts, pine-kernels, fruit and anything else they can find, taking anything that’s too difficult to prise open off to a tree which has wood rotten enough to jam the offending item into. These ‘anvil trees’ as they are called may be used by successive generations of woodpeckers and can be identified by the piles of opened pinecones and nuts on the ground beneath. If a woodpecker finds a nest with eggs or fledglings in it then this will be fair game too, they will even pro-actively follow and harass smaller birds in order to locate and raid their nests, aggressively fending off the desperate parents.

Sometimes a Great spotted woodpecker may be observed on the ground, quite often they will be using their long tongue rather like an anteater does; to probe inside an anthill for dinner.

His bill an auger is,

His head, a cap and frill.

He laboreth at every tree,

A worm his utmost goal.

(The woodpecker, by Emily Dickinson)

A B-H

2 thoughts on “The Great Spotted Woodpecker”