Woodcock, Scolopax rusticola, (scolopax being the genus name and rusticola coming from the latin words rusticus, meaning ‘rural’ and colere ‘to live’,) are arriving by the tens of thousands in the British isles at the moment, by the light of the full moon.

The ‘Woodcock moon’ as it is called is traditionally the last full moon of October or the first full moon of November. This year (article updated from when first published in 2023) it falls on the 15th of November)

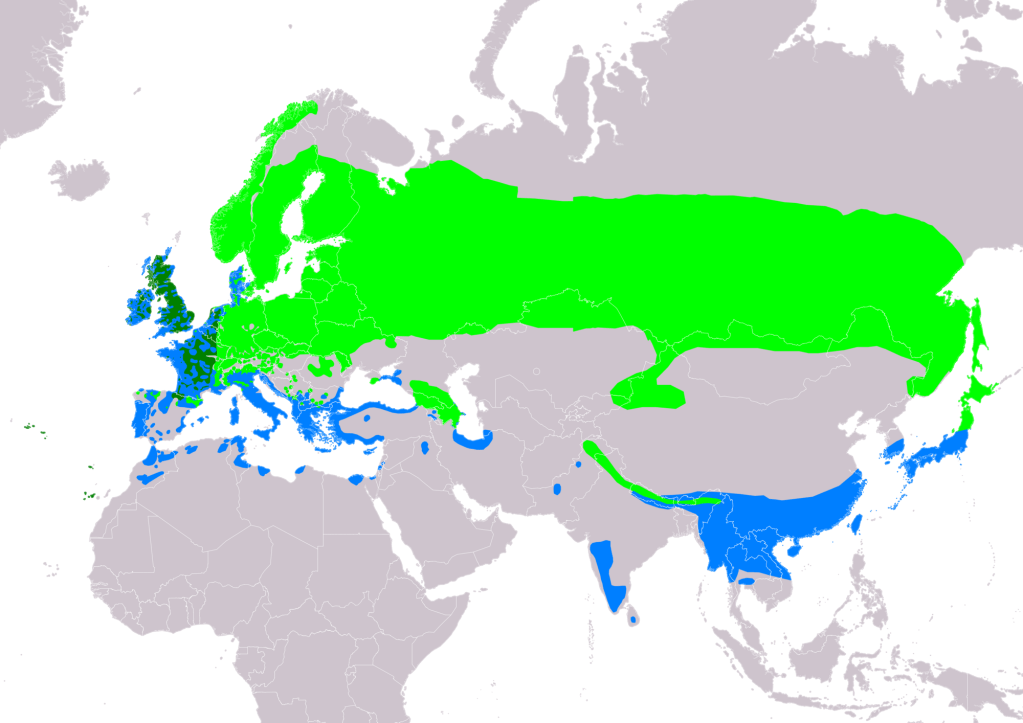

Around this time at places along the east coast, such as the Moray firth, Lindisfarne and Spurn head, thousands of Woodcock can be seen exhaustedly flapping inland, to flump down into the nearest bit of cover they can find and recuperate some energy after their long flight from their summer breeding grounds in Scandinavia and Russia. There are up to 60,000 breeding pairs in the UK and around 1.4 million birds spend winter here.

Taking advantage of the wind

The Woodcock take advantage of any northeasterly wind there might be at this time and over a million birds can arrive to add to the British isle’s resident population of over 50,000. They sometimes get so exhausted crossing the seas (they aren’t really built for long distance flying) that they they have been known to alight on fishing boats (that account is fascinating to read by the way) and will very often become confused by city lights and crash into buildings, being found dazed in the street the next day.

They are quite peculiar in appearance, and very hard to see in their natural habitat, having a mottled brown, camouflaged pattern which is perfectly adapted for autumn leaves. They also have prominent, shiny black eyes on the side of their head for seeing 360 degrees around them, biologists have discovered that as this species evolved and its eyes grew, its brain has slowly migrated to an upside down position!

An experienced countryman will look for their eyes to spot them hiding in the leaf-litter where they spend all day skulking on the forest floor. They can be flushed almost from under your feet which can make you jump! and they will jink and twist between the trees as they make their fast escape.

Woodcock also have a long, sensitive bill which they use for probing for worms, grubs, beetles, spiders, and other insects they can glean from the woodland floor, they have a strange way of feeding, walking heavily along the ground, often rocking back and forth to feel earthworms moving beneath the soil.

Roding

They are crepuscular or nocturnal birds, being most active around dawn and dusk. In the early summer the male Woodcock can be heard or seen roding over the forest canopy, flying a slow circuit over their territory and emitting a squeaking, grunting ‘kirrick’ noise which can be quite startling if one flies overhead when you don’t expect it!

Woodcock are polygynous, mating with several hens, with males establishing a breeding territory, and females picking the best mate based on their courtship displays, the Woodcock who can drum the loudest gets the girl!. The females will then lay a clutch of three or four eggs and sit for around three weeks, the chicks being independent by around a month old.

Do Woodcock really carry their chicks?

This bit of folklore has been the source of much fierce debate for centuries, some of the worlds leading ornithologists have almost come to blows arguing about it!

All I will say on the matter is that i’ve personally observed a Woodcock carrying a chick held tight to it’s breast with its legs, i’ve heard accounts from reputable witnesses and there is some (rather blurry) footage taken by a gamekeeper on his phone.

The 19th century naturalist Charles St John wrote about this, here is an excerpt from my first-edition copy of “Wild Sports and Natural History of the Highlands”;

” It is a singular, but well ascertained fact, that woodcocks carry their young ones down to the springs and soft ground where they feed. Before I knew this, I was greatly puzzled, as to how the newly-hatched young of this bird could go from the nest, which is often built in the rankest heather, far from any place where they could possibly feed, down to the marshes. I have, however, ascertained that the old bird lifts her young in her feet, and carries them one by one to their feeding ground. Considering the apparent improbability of this curious act of the woodcock, and the unfitness of their feet and claws for carrying or holding any subsatnce whatever, I should be willing to relate it on my own unsupported evidence; but it has been lately corroborated by the observations of several inteligent foresters and others, who are in the habit of passing through the woods during March and April”.

Pin Feathers

Woodcock, like their close relative the snipe have very prominent pin feathers. Pin feathers are stiff feathers that stick out of the leading edge of the woodcock’s wing, they are quite often used for painting and its become a tradition to paint Woodcock using their own pin feathers. A gun will quite often keep the pin feather in his cap as a badge to show he is adept enough a shot to have managed to bring down a fast, jinking Woodcock.

Game bird

Woodcock are considered to be a very noble game bird and some years a moratorium on shooting is voluntarily held by shoots when their numbers are worryingly low. Many shoots will try to maintain good habitats for Woodcock as they are held in such high esteem. Shoots can earn quite a bit of money from guns for a decent ‘cock’ shoot, although a lot of this money will be ploughed back into habitat maintenance for them, as they aren’t really a main profit driver compared to the Pheasant and Partridge. A chance of having a crack at a Woodcock being more of a bonus rather than an expectation.

There is even a ‘Woodcock Club’, which guns can become a member of if they have managed a ‘left and right’ at flushed Woodcock, this being a shot made with the left and right barrels of a side-by-side barrelled shotgun.

In the Northwest there are many woods they can be found, one of my favourite places to see them is at Birkett fell above Dunsop Bridge in the Hodder valley, they are also really common in the forestry at Gisburn forest and at Browsholme Hall in the Ribble valley where they can be seen, or heard roding over the driveway to the hall.

A B-H