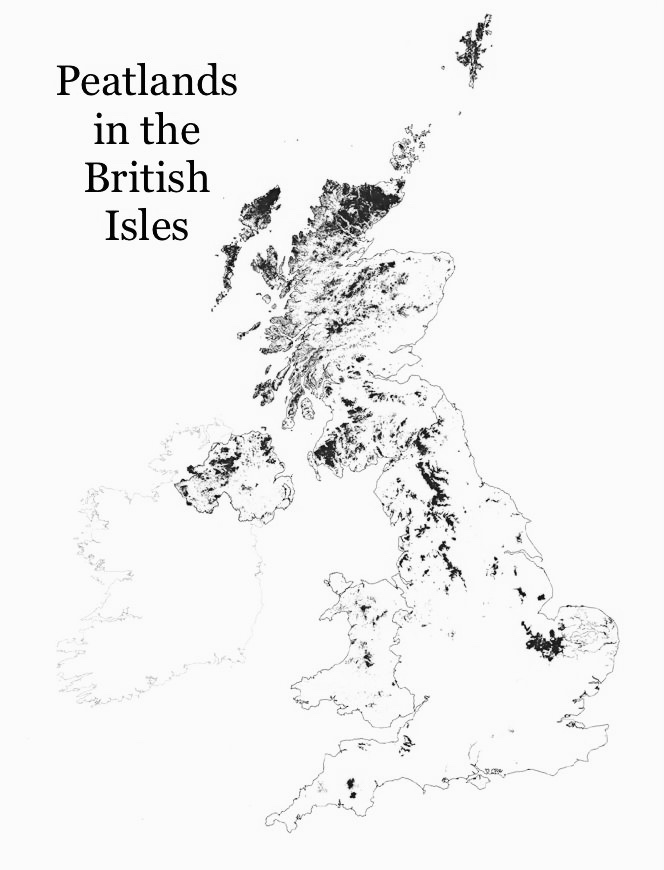

Peat is formed by the accumulation of centuries of decaying plant matter, around 1mm of peat is formed a year and on some peat-bogs the peat can be over 4 metres deep, making the peat at the bottom of these layers over 4000 years old.

Carbon Sinks

Peat-bogs are what are called ‘carbon sinks’, meaning they absorb Carbon Dioxide, (CO2) from the atmosphere, making them very valuable at the moment when we are putting so much into it, in fact almost 60% of peat is made up of carbon. Traces of some of the heavy metals we’ve released into the atmosphere can be found in peat too, after the Chernobyl disaster some parts of Pennine moors were even found to have become radioactive!

Water Absorptive

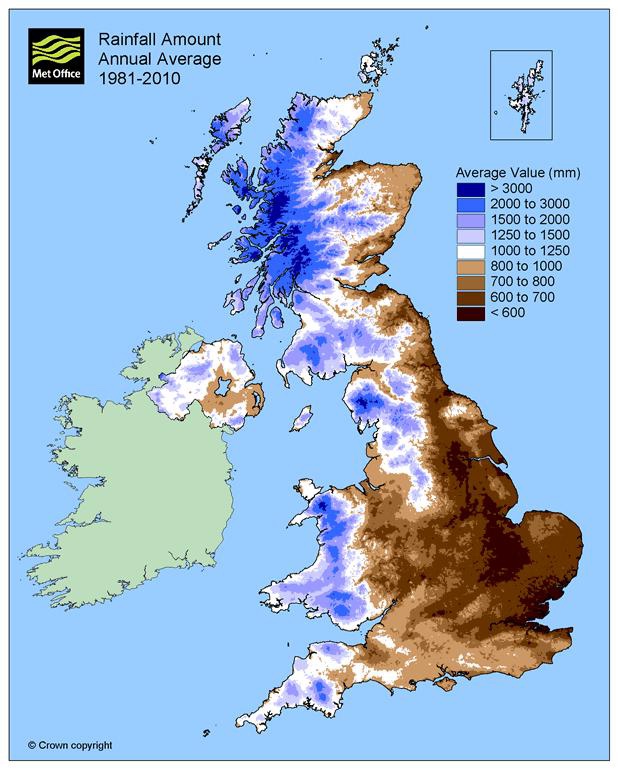

They also absorb water, huge quantities of it, like vast sponges, most of a bog is formed of Sphagnum moss and as any gardener will tell you it is excellent at retaining moisture in things like hanging baskets. Other moorland plants such as Bilberry, heathers, rushes, sedges and grasses such as Cottongrass are also very absorbent and help to slow the progress of rainwater on its endless cycle from the cloud to the land, land to rivers, rivers to seas and seas back into clouds again.

In recent years heavier rainfall and flooding have become such a regular occurrence, and are in the news so often, that landowners, land management groups and government bodies such as the Environmental Agency have realised that measures have to be taken to alleviate the problem. One solution is to restore peat bogs and utilise them as a buffer for H2O as well as CO2.

See this post for a brief look at our 3 main species of heather;

Fragile

Britain’s moorlands and peat bogs have suffered damage from many causes over time, acid rain, especially in the eighties, killed off large tracts of vegetation and further acidified the already very acidic peat.

Overgrazing has caused severe erosion in some areas too, in the Northwest this is more noticeable on moors like Pendle compared to those such as the Bowland fells. This is because income from Grouse moors has proved to be greater than that made from sheep grazing, therefore there has been an incentive to preserve the moors rather than ‘improve’ them into agricultural land.

Grazing animals should not be removed entirely though as some rare habitats, such as Waxcap grasslands for example, only exist on closely-grazed moorland, a fine balance must be struck.

In a couple of locations on the high Bowland fells damage caused by large colonies of Lesser Black-backed gulls has had to be repaired, their guano acidifies the peat, kills off plant cover and leaches into streams, poisoning aquatic life.

Burning

Wildfires on peatlands can cause some of the worst, and most obvious damage, the contentious practice of Controlled burning on grouse moors means that of all the large and uncontrollable wildfires that happened in the northwest in recent years, such as the huge fires that broke out on Saddleworth moor above Manchester in 2018 and 2019, few large ones occurred on grouse moors.

This is because the practice of controlled, and fast, burns to encourage new plant growth prevents the build up of lots of dead, and highly flammable, plant material. A really big wildfire, given enough fuel to burn too fiercely for firefighters to control, can burn deep into the peat and smoulder away underground, in a similar way to coal-seam fires, some of which can burn for months.

These hot fires can erupt again further away on the moor, burning new gullies into the peat and literally eating away at it, unlike the ‘cool’ burning fires that gamekeepers light when heather burning, which do not effect the underlying peat, they will also destroy any seeds in the soil, preventing vegetation from regrowing.

The erosion from rainfall washing away the ashes and dry, exposed peat after a wildfire has scoured it clean can be catastrophic and very long-lasting, though it will also be a problem when shoots are over-zealous with their burning, which many unfortunately are, this too leads to run-off into water-courses, not something you want if they are your drinking water supply.

Read more about heather, or controlled burning in this article;

Erosion

Erosion by visitors traversing unpaved parts of the moors can be hugely damaging too, especially at very popular sites like the summits of the Lakeland hills and Pendle. The worn-out, denuded courses of the most popular paths can be seen from miles away and these paths can turn into new watercourses, particularly where walkers avoid puddles in an effort to prevent damage to expensive walking boots by walking around them, thus turning a metre-wide path into one the width of a main road.

Restoration work in Bowland

On the Bowland fells Peatland restoration work was started in the 2000s and since then tens of acres of peat bog have been restored. On Abbeystead Estate alone over 78% of damaged and eroded peat has been restored and restoration work is currently being carried out on moors above Dunsop bridge, which was flooded by a sudden downpour that also caused the village of Wray to be flooded in 1967.

This month (Oct 2023 as of writing) Lancashire County Council secured a £2.4million investment to restore 1,370 hectares of peatlands at 10 sites around the county including Abbeystead.

Restoration techniques;

Several techniques are used to try to fix damage to peat bogs and increase the amount of water they can hold, these are some of them;

Blocking ditches and gullies

Gullies and drainage ditches can be blocked, this can be done with coir (made of coconut fibres), wool, timber or other materials to flood bogs and create pools and splashes, government grants in the past have paid for hill farmers to dig drainage ditches to create farmland, but now they are paying for them to be blocked again!

Lowering the ph of the peat

Peat has a high ph of around 4.5 which means it is acidic, often bare peat can be very hard for plants to establish themselves on as it is so acidic therefore the ph will be artificially lowered to give plants a helping hand.

This is done by applying ‘Lime’ or Calcium Carbonate (CaCO₃), as the high moors can be very difficult to reach helicopters are often used (as in the video below) to drop bags of this 1 tonne at a time. Grass seeds and sphagnum Moss ‘brash’ will be added to this too, the speed that bare peat is recovered by new plants after this is quite surprising and after a few years the roots of heather and bilberry will reinforce the peat further.

Hagg re-profiling

On the fell-tops you may have to navigate around towering stacks and banks of peat, these can often be quite imposing, looming over 6ft tall and are called ‘peat haggs’. They erode inwards from the edges, much like a melting ice berg, leaving bare peat and sometimes bare bedrock behind them, on some parts of the moors work is being done to re-profile them.

The edges will be remoulded to a slope rather than a cliff to slow the trickle of water down them, also any overhangs, ‘drip-edges’ as they are called, are removed to stop water dripping from the edge eroding and undercutting the peat further.

Wheel-ruts

One of the most efficient ways of doing all these jobs is with mini-diggers, these are easy to get up onto the moor on the narrow lanes and as they are lightweight with caterpillar tracks the damage they cause to the already fragile moors is minimised.

Wheel-ruts are responsible for irreparable damage to many of the world’s landscapes, as a quick look at any where on the planets surface from google earth will testify, and on the moors these ruts can quickly erode in heavy rain turning into deep gullies or even entirely new watercourses.

Conclusion

Whilst centuries of exploitation has caused enormous changes to the British landscape, they haven’t all been negative or unfixable. We are also, as the work done on the moors to turn them into carbon and rainfall buffers proves, very capable and creative when it comes to mending things, historically we are a nation of scientists and engineers after all!

Further reading:

https://www.lancswt.org.uk/our-work/projects/peatland-restoration/lancashire-peat-partnership

https://www.grosvenor.com/rural-estates/peat-restoration-reduces-carbon-emissions

https://www.yppartnership.org.uk/

https://www.gwct.org.uk/policy/briefings/driven-grouse-shooting/conservation-on-grouse-moors/

https://www.moorsforthefuture.org.uk/our-work/restoring-blanket-bog/repairing-bare-peat

https://www.iucn-uk-peatlandprogramme.org/projects/cumbria-peat-partnership-cpp

If you have any further links that you think should be included here or anything else you think could improve this article please feel free to comment so I can add them.

A B-H

2 thoughts on “Peatland Restoration in the Northwest of England”