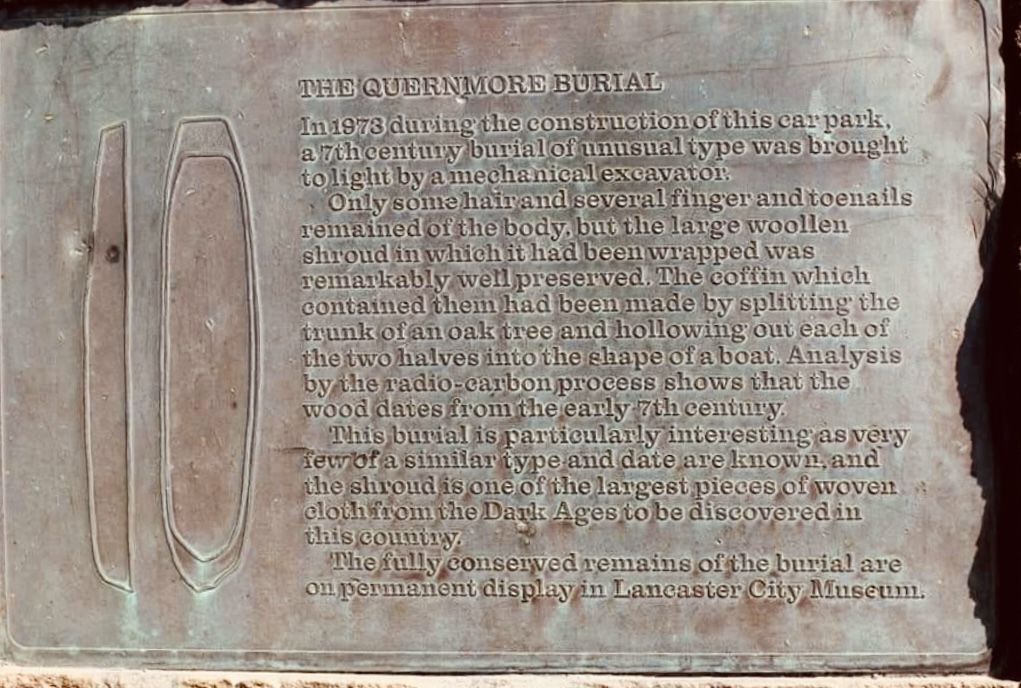

Quernmore Dark Age Burial

In 1973 a dog walker, James Marshall, was walking his dog near Jubilee Tower on the fells above the village of Quernmore. Recently builders had been constructing a car park for the tower, a popular local landmark and viewpoint, and had been removing peat with a digger.

Peculiar wooden artifacts

As he watched over his dog and looked around the building site he saw something peculiar sticking out of the ground that the digger had disturbed from the peat, upon further inspection it appeared to be a wooden canoe.

Realising that that this might be of some importance and interest to historians Mr Marshall contacted Lancaster City Museum, who came out to inspect the find. When they arrived and had a closer look, they found there was not one but two of the peculiar wooden canoe-shaped artifacts, one had unfortunately been crushed by the digger, but the second, the one Mr Marshall had spotted, was largely intact.

The team managed to save this artifact from further damage using the time-honoured technique of wrapping it in wet newspaper, further wrapped in plastic sheets to stop the moisture from evaporating. This method prevents ancient wood from splitting, disintegrating and turning into dust upon drying out. Then they carefully took the objects to their laboratory to examine them in a safe and controlled environment.

What the team discovered was that the two large pieces of wood were in fact both originally part of one object; an ancient coffin.

Ancient Coffin

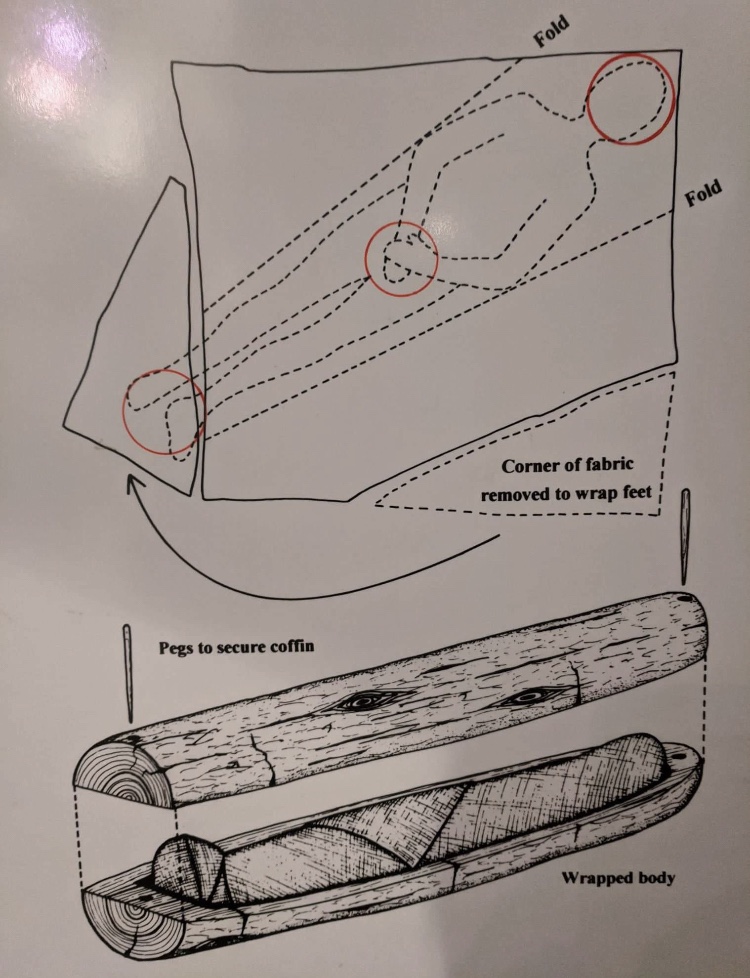

The piece that James Marshall had found was the bottom half, the base, of the coffin, with the other half, the section that had been crushed by the digger, being the top half. Both parts are made out of the hollowed out trunk of an Oak tree and would have originally been pegged together, unfortunately the top half had already received significant damage due to penetration from the roots of heathers and other moorland plants, so the unwitting digger driver wasn’t entirely responsible for its loss!

In the lab, the archaeological team proceeded to inspect the contents of the coffin; the remnants of its inhabitant, which were carefully wrapped in a woolen shroud.

Woollen Shroud

The shroud turned out to be composed of two sections of one sheet, one large, and one small, with the second, smaller section turning out to be the corner of the larger one. The corner had been cut off to wrap the feet of the deceased, who seems to have been taller than whoever had aquired the shroud had thought. Within the shroud the team found all that remained of the body.

Bone does not last long in peat, the acidic soil eats it away over a matter of decades, leaving only the more durable body parts remaining, in this case the team only found hair, fingernails and toenails, the positioning of these within the shroud told that the body had been lain diagonally across the shroud.

Radiocarbon dating

Although the square woolen shroud had not been quite big enough to wrap the body in its entirety it still turns out to have been the biggest piece of woolen fabric retrieved intact from the dark ages. Since its discovery the Oak wood of the coffin has been carbon-dated, giving a time frame for the construction of the coffin and the internment of it and its contents within the dark peat of the Bowland Fells.

Although radiocarbon dating is one of the most useful methods for determining the age of an item made of organic materials, it is not the most exact, the dating of the Quernmore coffin turned out to be somewhere around 600 to 700 AD, about 1350 years ago, give or take 100 years, in a period of time known as the ‘Dark ages’, due to a lack of records or much knowledge at all about this stretch of history.

Similar canoe-shaped coffins constructed of hollowed out Oak trunks, constructed in the same way out of two halves pegged together, have been found elsewhere in the North of England, several were found near Featherstone Castle at Haltwhistle in Northumbria by labourers digging a field-drain in 1825, and, also near Haltwhistle, at Wydon Eals and Rylstone in North Yorkshire.

Irminsul, the world-tree

Radio-carbon dating of these coffins placed them in the same era as the one at Quernmore, around the 7th century, and it is known that the early Saxons buried their dead in this style. At the time they invaded Britain these isles were dominated by forests of native trees such as Oaks, and the Saxon belief system placed the Oak in the centre of things, literally being the very pillar which supported their world, called Irminsul, very much like Yggdrasil, the ‘world tree, of the Norse faith.

Both the Saxons and Norse believed that the world tree, the Oak at the centre of the universe, linked the earthly world to the heavens, and that the internment of a body physically within an Oak tree allowed the soul of the deceased a quick entry to heaven. So this may have been a reason why this style of coffin, two halves of an Oak trunk pegged together, was used for a while, of course this is just a wild surmise and we’ll never really know.

What we do know is that this part of the world, on the hills overlooking the Fylde plains and what would have been the ancient, now submerged, land of Amounderness, has always held a lot of significance for ancient cultures, with several archaeological sites nearby including Bleasdale Circle, an ancient wood-henge which i’ll write about soon.

The coffin was donated to Lancaster City Museum, where it is on display now, by Lady Sefton, who was the owner of the land that the coffin was found on and both the museum and the original burial site of the coffin are both well worth visiting. If you do go to Jubilee tower above Quernmore make sure to walk up the to the top of it and admire the views, then you might understand why this location was deemed by the Saxons to be such a perfect place to bury one of their own.

A B-H

2 thoughts on “Unnatural Histories, A Grim Discovery at Quernmore”