The common perception of moths is as dull-coloured, crepuscular creatures, more often than not seen at night or appearing as the sun goes down to thunk into window panes, or, if they get into the house, lightbulbs. But, as with most things in nature, things aren’t quite so simple and straight forward, as there are just as many day-flying moth species as night-flying, and many of both variety are anything but dull.

Scarlet livery

The Cinnabar moth, Tyria jacobaeae, named after the colour of its wings, which are the same unique shade of red as the mineral Cinnabar, is one of the most startling looking of these day-flying moths, and can be seen darting about the undergrowth even in full sunshine, made obvious by its bright scarlet livery, which it sports against a velvety black background.

They tend to flutter about and then suddenly drop into vegetation, but rarely stay still long enough to be easily identified, and in appearance it looks very similar to several other species, including the 6-spot Burnett (see images below), which is also frequently seen flying in the daytime.

Although has red hind-wings just like Burnetts, it can be distinguished by the fact that it has both spots and a bar on its forewing upper surface, with the bar along the leading edge of the wing, rather than just spots like the Burnet, and it also has slim antennae, rather than the idiosyncratic hooked and club-ended antennae of the Burnett.

Warning colours

The use of bright and distinctive colour combinations by living organisms as a defence mechanism is called aposematism and, as well as the common red-and-black combo that the adults wear, Cinnabar moth caterpillars use the equally alerting two-tone of black and yellow.

There are several reasons why this colour pairing is perfect for protection against predators, one is that it provides high contrast against the background, which in their habitats is usually green, another is that it is resistant to shadows and changes in light conditions, as black does not change during the day, whereas if they were white this could be perceived as pink in the early morning or late evening sun, which wouldn’t be quite so threatening!

Breeding cycle

Cinnabar Moths lay a cluster of eggs on the underside of a Ragwort leaf around June, and when the caterpillars emerge from the eggs they are small in size and yellow in colour. As the voracious caterpillars gorge themselves on the plant, which they eat all the parts of, they grow bigger and turn a bright yellow/orange alternated with black hoops.

It is a poisonous plant to most creatures, containing toxins including pyrrolizidine alkaloids, but remarkably the caterpillars are able to extract the poisons, and store them in their bodies to make themselves unpalatable to birds that might eat them. While the black and yellow pattern is interpreted as warning coloration by almost all bird species the Cuckoo in particular will seek out Cinnabar Moth caterpillars and eat them with impunity.

Despite the bright appearance of the caterpillars I’ve noticed that when they are feeding on the flowers of Ragwort their yellow and black coat helps them to blend in and make them inconspicuous from a distance.

By about August many colonies of the hungry caterpillars will have stripped their food plant bare, some leave and go wandering, searching for another Ragwort to eat, but others turn cannibalistic and turn on their siblings, survival of the fittest in its most brutal form!

When September comes, the Cinnabar Moth caterpillars will be fully mature, they then descend to the ground, pupate and overwinter, awaiting the arrival of next spring. Next May, they will emerge from their pupae, fly off to seek partners, mate, lay eggs on Ragworts and start the cycle all over again.

‘Ragwort Mania’

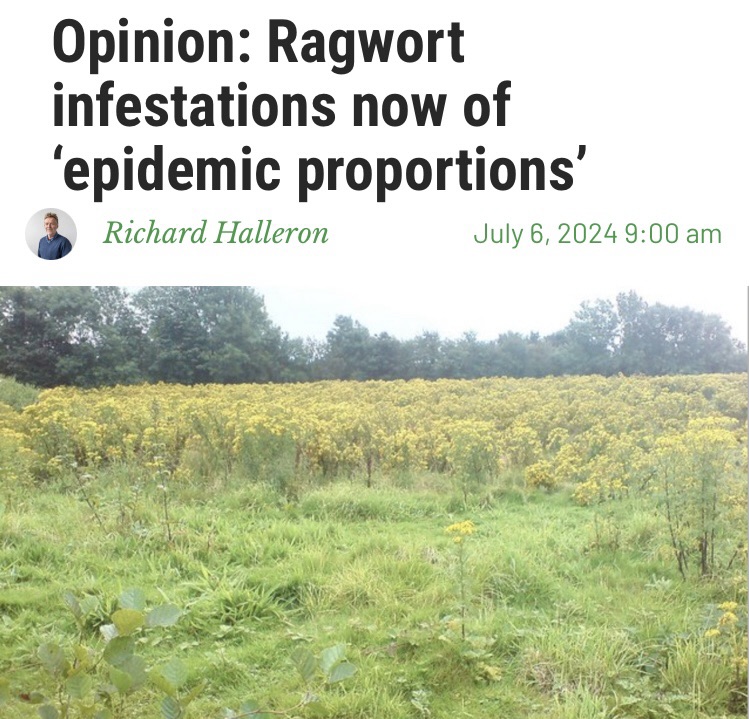

Whilst the Cinnabar moth is fairly common their numbers have been in decline recently, possibly due to the widespread phenomena kmown as ‘Ragwort mania’.

Ragwort, Jacobaea vulgaris, is so interconnected with the Cinnabar that they share part of their Latin names, ‘Jacobaea’, with one another, this name, (being the latinised version of James), is supposedly taken from an association with the Apostle St James and it is said that Ragwort will never flower before his feast day on 25th July, although it seems no-one has told the Ragwort that!

Somewhat ironically St James is the Patron Saint of Veterinarians, yet the duo which bear his name suffer as well-intentioned landowners, farmers, and in particular horse-owners, pull up, cut or crush Ragwort plants out of a fear that their animals will become poisoned if they eat it, incurring hefty vet’s bills.

This ‘mania’ can manifest itself almost as if there is a battle of two belief systems, with over-zealous livestock owners trying to destroy every visible sign of the plant whilst exasperated conservationists try their utmost to defend it, believe me when I say that the ‘War of the Wort’ can get quite heated!

This fear isn’t unfounded though, Ragwort can be toxic for livestock, causing liver damage, or, if enough is eaten, brain damage and death. However most livestock won’t touch Ragwort unless they have grazed out everything else as they seem to instinctively know it is toxic and, when fresh and green it is unpalatable to them.

The liver has an amazing ability to regenerate itself and symptoms of Cirrhosis, liver failure, only start to become apparent when under 20% of an animal’s liver is left functional. The vast majority of grazing animals, domesticated or wild, do not live long enough to consume enough Ragwort for these symptoms to become evident, the exception being domesticated Horses.

Domesticated Cattle and Sheep (the latter having a high resistance to Pyrrolizidic Alkaloids like Ragwort toxin anyway) are almost always slaughtered long before they reach the average age of a Horse. As weight-loss is often one of the first symptoms of cirrhosis cattle and sheep suffering from it would otherwise be slaughtered due to being non-productive, without blood tests for pyrrolizidine and other alkaloids necessarily having been carried out .

Also horses, with their greater value, maintenance expenditure and lifespan, are fed hay more often and for longer than cattle or sheep, so are more prone to consuming Ragwort which has inadvertently been cut and baled, as cut Ragwort maintains its toxicity yet the animal cannot tell it’s there.

In fact horse-owners may be doing themselves a disfavour with their obsession over Ragwort as other causes of equine liver disease will get overlooked and preventable casualties occur; the Megalocytosis caused by pyrrolizidine alkaloids being almost indistinguishable to that caused by mycotoxins, which are toxic compounds caused by mould, mostly from ergot mould growing on poorly-kept feedstuffs or tall Fescue grasses.

Other species which Rely on Ragwort

DEFRA (the Department for Farming and Rural Affairs) have estimated that J. vulgaris supports over 200 invertebrates, of which 30 are entirely dependent on it as their foodplant, these include the;

Antler Moth

White-Tailed Bumblebee

Small Skipper Butterfly

Red Soldier Beetle

Thick-legged Flower Beetle

Northern Brown Argus

Marmalade Hoverfly

Small Tortoiseshell Butterfly

Small Copper Butterfly

The Law on Ragwort

Legally up-rooting any wild plant, including Common Ragwort, anywhere in Great Britain without the authority of the landowner is a criminal offence under Section 13(1)(b) of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

On the other hand if you have harmful weeds growing on your land the law says you should stop them spreading on to agricultural land that’s used for grazing, producing forage feeds like silage and hay or growing crops, and you may be fined if you do not demonstrate you have taken measures prevent the spread of Ragwort.

In the following poem pastoral poet John Clare shows his appreciation of ‘weeds’ like Ragwort, describing his feeling that the English countryside would be somehow duller without the golden-yellow of the Ragwort to adorn it.

The Ragwort, by John Clare

Ragwort, thou humble flower with tattered leaves

I love to see thee come and litter gold,

What time the summer binds her russet sheaves;

Decking rude spots in beauties manifold,

That without thee were dreary to behold,

Sunburnt and bare– the meadow bank, the baulk

That leads a wagon-way through mellow fields,

Rich with the tints that harvest’s plenty yields,

Browns of all hues; and everywhere I walk

Thy waste of shining blossoms richly shields

The sun tanned sward in splendid hues that burn

So bright & glaring that the very light

Of the rich sunshine doth to paleness turn

and seems but very shadows in thy sight.

(track is ‘Northern Lites’ by the Super Furry Animals)

A B-H

(July 2024)

Beautiful

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks 🙂

LikeLike