(Caroline Legg)

The Common Bullfinch, Pyrrhula pyrrhula, is perhaps the best-known species within the Pyrrhula genus, aptly named after the Greek word pyrros, meaning ‘flame-colored’.

It is the male who is most strikingly coloured, sporting a rich, rosy-pink breast, black cap, and grey back. In contrast the female is more conservatively dressed with a lighter pink breast and a greyish cap, however they both share the species’ characteristic black wings with white wing bars.

Being a finch both sexes have a stout, conical bill perfect for their preferred diet of seeds and buds, in the north of England this has given them the nickname of ‘Thickbill’.

Caroline Legg

Sedentary Species

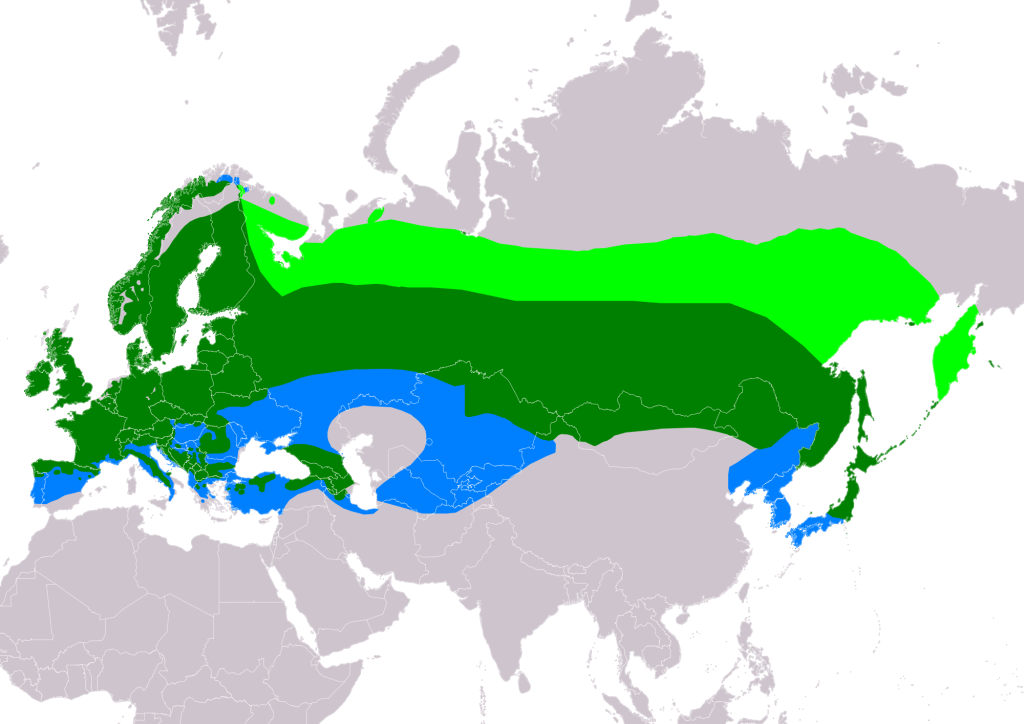

This finch is found across the northern hemisphere in a broad swathe stretching from the British isles to Japan and are mostly a sedentary species, staying close to their home territories. They only migrate if the weather turns particularly harsh, when they will form flocks and seek areas with denser cover for protection from the elements.

If an individual Bullfinch finds a particularly productive food source in its territory and habitually frequents it other Bullfinches will observe and follow the first finch until a feeding flock forms.

We’ve observed this in our garden, where last year we had only the occasional visiting finch this January a flock of 7 males and 2 females is making several visits a day to our feeders, hopefully they’ll nest nearby.

Distribution map of Bullfinch

according to IUCN data

Light green: breeding

Dark green : resident

Blue : non-breeding

Bullish Behaviour?

Despite their namesake Bullfinches are not particularly bullish in their nature, being of a quieter, gentler disposition than other garden bird species. They may even get bullied from the bird table by tits and other smaller birds and will retreat to the shrubs, waiting until the coast is clear before returning.

Shrubs and trees are their natural habitat, where they can find the seeds, buds and fruits they primarily feed upon. Their tendency to eat the latter means they play a useful role in spreading the seeds of species like Rowan, Guelder and Hawthorn.

Unfortunately it is also why they have been persecuted in the past, as this predilection for fruit made them unpopular with owners of orchards and fruit farms. Until not long ago, certainly within living memory for some, farmers would pay children to scare off Bullfinch from fruit trees by shouting and banging tins and cans.

This noisy spectacle has been consigned to the past though, along with the tradition of keeping at least one fruit tree in the farmyard, and many orchards have been grubbed up over the decades in favour of imported fruits, so although they may not be harassed anymore they have been deprived of one of their favourite habitats.

(Caroline Legg)

Characteristic Call

It must have been fairly easy for children to have identified intruding Bullfinch as, apart from their colourfully obvious appearance (although they can be surprisingly hard to spot in thick cover), they have a unique vocal repertoire.

As they fly overhead they will occasionally issue a soft, ‘heu’ call which can also be described as a quiet, low, melancholic whistled ‘peeu’ or ‘pew’. Their song is often described as ‘mournful’ too, quiet and scratchy, containing fluted whistles that can only be heard only when close.

Although they tend to be close-mouthed (or should it be close-beaked?) in the wild, captive Bullfinch can be very vocal, they are even capable of mimicking or being taught simple melodies. (I thought about including a link here to a video of a captive Bullfinch singing but can’t quite countenance the thought of keeping these beautiful wild birds in cages.)

In the past they would be caught with fine horsehair snares and kept in cages, travelling pedlars would teach them to whistle a tune through repetition and display them to earn a few pennies. This is still done in other countries but not in the UK where they are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, which makes it illegal to intentionally kill, injure, or take them, or damage or destroy their nests while in use or being built.

Breeding Behaviour

The courtship behavior of the Bullfinch is quite fascinating, the male will present seeds or buds from his beak to the female to strengthen their bond before the breeding season begins. Being a monogamous species this bond may last for a long time if not for life, with the bond being re-enforced every spring.

Nesting occurs in spring, when the female will build a neat, cup-shaped nest in dense and secluded cover. This meticulously assembled construction is composed of two sections; a foundation platform of small twigs and the nest itself, woven out of lichen, moss and similar materials and lined with a thick layer of roots, grasses or coarse animal hairs, in this nest she lays 4-7 eggs, which are a finely speckled pale green or blue.

Both parents share the responsibility of incubation and then feeding the fledglings, this is common in birds which exhibit such bonding behaviour, these will leave the nest after a couple of weeks but continue to be cared for by their parents for a little while longer.

(Notts Ex-miner)

Conservation Status

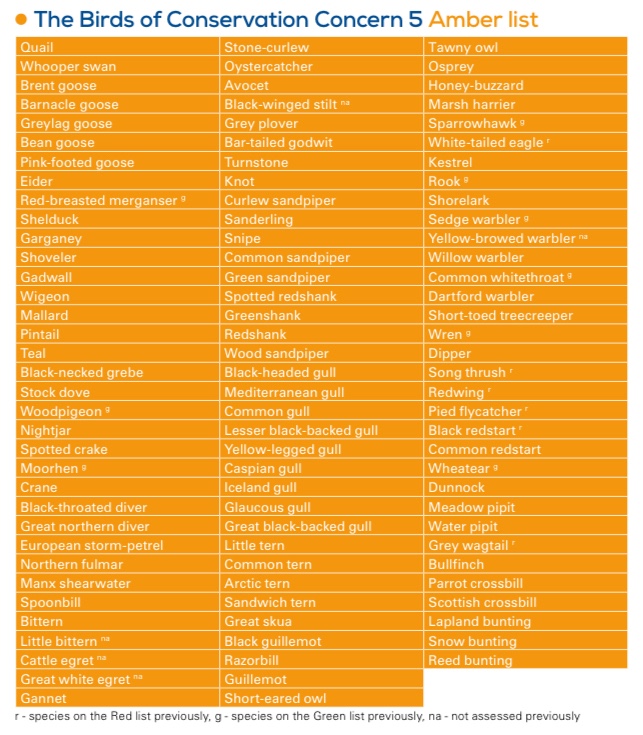

Bullfinch are currently catalogued as Amber under the Birds of Conservation Concern list or ‘Red List’, this indicates that they are a species of moderate conservation concern.

Historically, from the mid-1970s, Bullfinch populations experienced significant declines, dropping by about 40% from their numbers in the 60s. This is thought to be down to habitat loss and changes in agricultural practices that reduced food availability, particularly the loss of hedgerows.

However, there have been signs of recovery since around 2000, with the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and other conservation organisations noting an increase in sightings in gardens and woodlands, which suggests a positive trend in population recovery. This upturn has been attributed to conservation efforts like habitat restoration and improved management practices that provide more nesting and feeding environments.

Conservation efforts for the bullfinch include promoting the growth of native trees and shrubs that provide the buds and seeds they feed on, particularly during winter when food is scarce. Organizations like the Wildlife Trusts encourage gardening practices that support wildlife, such as maintaining dense hedgerows and planting species like Hawthorn and Blackthorn where Bullfinch can nest.

Despite these measures, challenges remain due to ongoing habitat degradation, and continued monitoring and conservation work is crucial to ensure the bullfinch’s population continues to thrive. Public involvement in birdwatching and citizen science projects also plays a significant role in gathering data to inform future conservation strategies.

Plate 69 from the Nederlandsche vogelen

The Bullfinches

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928)

Bother Bulleys, let us sing

From the dawn till evening! –

For we know not that we go not

When the day’s pale pinions fold

Unto those who sang of old.

When I flew to Blackmoor Vale,

Whence the green-gowned faeries hail,

Roosting near them I could hear them

Speak of queenly Nature’s ways,

Means, and moods,–well known to fays.

All we creatures, nigh and far

(Said they there), the Mother’s are:

Yet she never shows endeavour

To protect from warrings wild

Bird or beast she calls her child.

Busy in her handsome house

Known as Space, she falls a-drowse;

Yet, in seeming, works on dreaming,

While beneath her groping hands

Fiends make havoc in her bands.

How her hussif’ry succeeds

She unknows or she unheeds,

All things making for Death’s taking!

–So the green-gowned faeries say

Living over Blackmoor way.

Come then, brethren, let us sing,

From the dawn till evening! –

For we know not that we go not

When the day’s pale pinions fold

Unto those who sang of old.

A B-H

(Jan 2025)