(author)

You may find many treasures on a spring-time walk down our countryside’s old lanes; the delicate white flowers of Blackthorn, scarlet Campion, or butter-yellow Cowslip, yet for me one of spring’s gems shines brighter than the others, and that is the pink and white bloom of the Crabapple tree.

(Rosser1954)

Malus sylvestris

The scientific name of the Crab, or Wild Apple is Malus sylvestris and they are a native species distinct from the domesticated apple Malus domestica, which derives from Central Asian species.

A small deciduous tree, typically found in our older hedgerows and woodlands, their fruits are smaller than cultivated apples, usually 2 to 4 cm in diameter, green or yellow, sometimes flushed with red, and notably tart.

They are widespread and hardy, thriving in a wide variety of soils and climates, from the mild, chalky downs of southern England to the rough and rugged hills of Scotland.

In spring they produce delicate white or pink blossoms, attracting pollinators like bees and hoverflies, and fruit in late summer to autumn, providing food for wildlife.

Ecologically Important

Crabapples play a significant role in our countryside’s ecology, their flowers are a nectar source for insects, while their fruits sustain birds, mammals, and even invertebrates during autumn and winter.

Species such as blackbirds, thrushes, and Fieldfare rely on crabapples as a food source, while mammals like voles and badgers consume fallen fruit. The trees also serve as habitat, with their gnarled branches offering nesting sites and shelter.

As a native species, Malus sylvestris contributes to the genetic diversity of our domestic apple trees, and is often planted besides orchards to ensure a good fruit set, especially if the domestic trees are self-sterile or have limited pollination.

However, hybridisation with cultivated apples has led to concerns about the purity of wild populations. Conservation efforts in some areas aim to protect pure Malus sylvestris stands, particularly in ancient woodlands, to preserve this genetic heritage.

(Kmtextor)

Culturally Significant

Crabapple trees are deeply rooted in our cultural heritage, archaeological evidence suggests that wild apples were gathered as early as the Neolithic period, long before the introduction of domesticated apples by the Romans. In Celtic mythology, apples were associated with immortality and the Otherworld, as seen in tales of Avalon, the “Isle of Apples.”

While these stories likely refer to apples broadly, crabapples, as the native species, would have been the most familiar to early inhabitants.

In medieval times, crabapples were used for food, medicine, and cider production, and their high pectin content made them ideal for ‘verjuice,’ a sour juice used in cooking and preserving. Crabapple jelly, made by boiling the fruit with sugar, was and still is a staple in households, and the fruit’s astringency is valued in herbal remedies for treating digestive issues.

Folklore also abounds with references to crabapples. In some regions, ‘apple wassailing’ ceremonies, performed to ensure a good harvest, include crabapple trees.

Old traditions, such as throwing crabapples into orchards to bless the trees, still persist in rural areas, particularly in the West Country.

Culinary and Horticultural Uses

While crabapples are too tart to eat raw, their culinary potential is vast, although nowadays they are most commonly used to make crabapple jelly, a translucent, ruby-colored preserve that pairs well with meats, cheeses, and scones, (I’ll publish a recipe for it later this year.)

The fruit’s natural pectin eliminates the need for additional gelling agents, making it a favorite among home preservers, in fact below is some Crabapple jelly that I rooted out from our cupboard.

Crabapple cider, often blended with sweeter apples, is another traditional product, particularly in regions like Herefordshire and Somerset, be cautious though it’s lovely stuff but very potent!

Modern foragers and chefs have “rediscovered” crabapples, incorporating them into chutneys, sauces, and even desserts, as their sharp flavor adds complexity to dishes, and their ornamental appeal, thanks to their colorful fruit and blossoms, has made them popular in gardens.

Unfortunately the little tree I’ve got in our garden has only ever produced blooms in the 5 years since I got it and hasn’t fruited once yet.

I can’t remember which variety ours is as it was a bargain-bin plant due to it having a broken leader (main central branch) but its white blossom tells me it’s most likely an ornamental cultivar like ‘John Downie’ (white blossom, red fruits), ‘Golden Hornet’ (yellow fruits), or ‘Evereste’ (red fruits), these are valued for both their spring blossom and autumn fruits, and ideal for small gardens or hedges.

Crabapples in English Literature

In English literature crabapples often symbolise bitterness, unripeness, or unfulfilled potential, reflecting their tart, inedible nature compared to their cultivated cousins.

The tiny fruit carry a hefty metaphorical weight, being tied to themes of disappointment, nature’s harshness, or human imperfection.

In Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Act 2, Scene 1), Titania mentions “crab” apples in a fairy’s diet, evoking the rustic, untamed quality of the natural, or fairy, world, contrasting it with our refined, or manmade one.

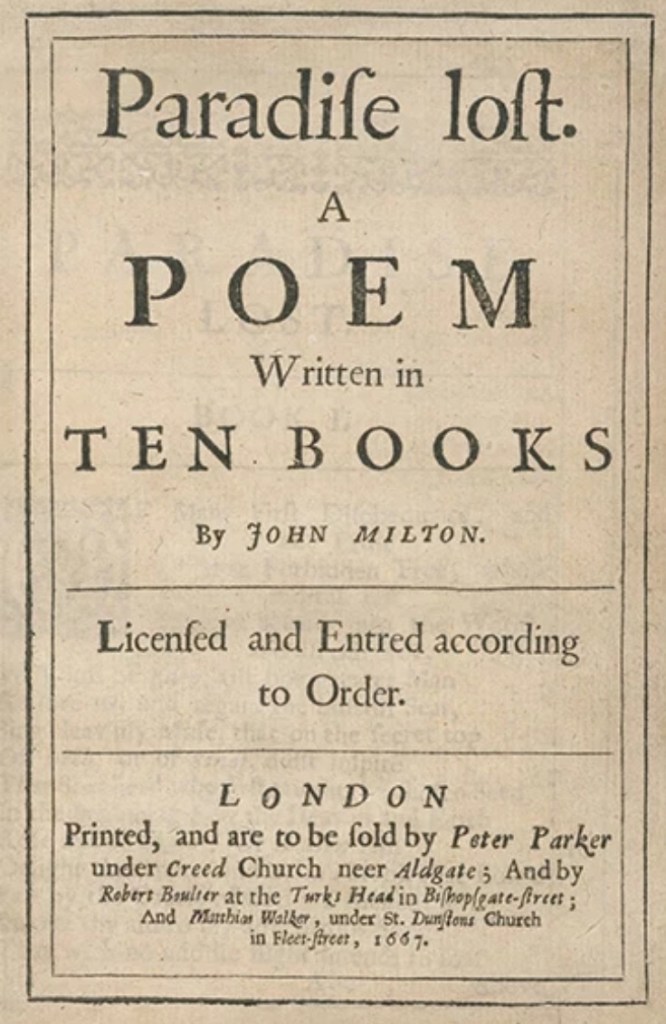

John Milton uses crabapples in Paradise Lost (Book 10), describing the forbidden fruit post-Fall as turning to “bitter ashes” or akin to “crabbed” apples, symbolising sin’s disillusionment. The sourness mirrors Adam and Eve’s regret, a stark departure from the sweet promise of Eden.

In Romantic poetry, crabapples surface in passing, like in Wordsworth’s The Prelude, where rural imagery includes wild fruit, hinting at nature’s unpolished beauty and the poet’s nostalgic connection to untamed landscapes. Similarly, Keats’ Ode to Autumn doesn’t explicitly name crabapples but evokes their ilk in “ripen’d fruit,” suggesting both abundance and the fleeting, imperfect ripeness of life.

Victorian literature leans into crabapples for social commentary. In Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, the orphaned Jane compares herself to a “crabapple” in contrast to the “roses” of privileged girls, underscoring her plainness and resilience. Thomas Hardy, in The Woodlanders, uses crabapple trees to depict the rugged Wessex countryside, their gnarled forms paralleling the characters’ tangled lives and unfulfilled desires.

Modernist and later works shift focus but retain the symbol. In D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love, a crabapple tree’s “sour fruit” mirrors the characters’ emotional discord, its wildness clashing with societal refinement.

More recently, in children’s literature like Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, crabapples in the untended orchard signify neglect but also potential for renewal, mirroring Mary’s transformation.

The Flowering Crab-apple

The moon is turning the corner of the porch

For a glimpse of her glorious beauty adored.

The east wind slows down for her sweet perfume

In the beaming waves of her budding blooms.

I light a long candle, fearing she’d drowse away,

So I won’t miss any moment of her short stay.

(Written in Huangzhou, China, 1083 by Su Shi, better known as ‘Dongpo’)

A B-H

(April 2025)