We’re lucky where we live, in that we have access to the countryside only 100 yards from our front door, you need only walk round the corner, cross the road and you’re on a stretch of Common Land called Hapton Moor.

I walk up there at least once a week and almost always find something interesting; maybe a new plant establishing itself in the scrubby, abandoned industrial land at the top, or an overlooked species that has been growing there all along which I simply haven’t noticed before.

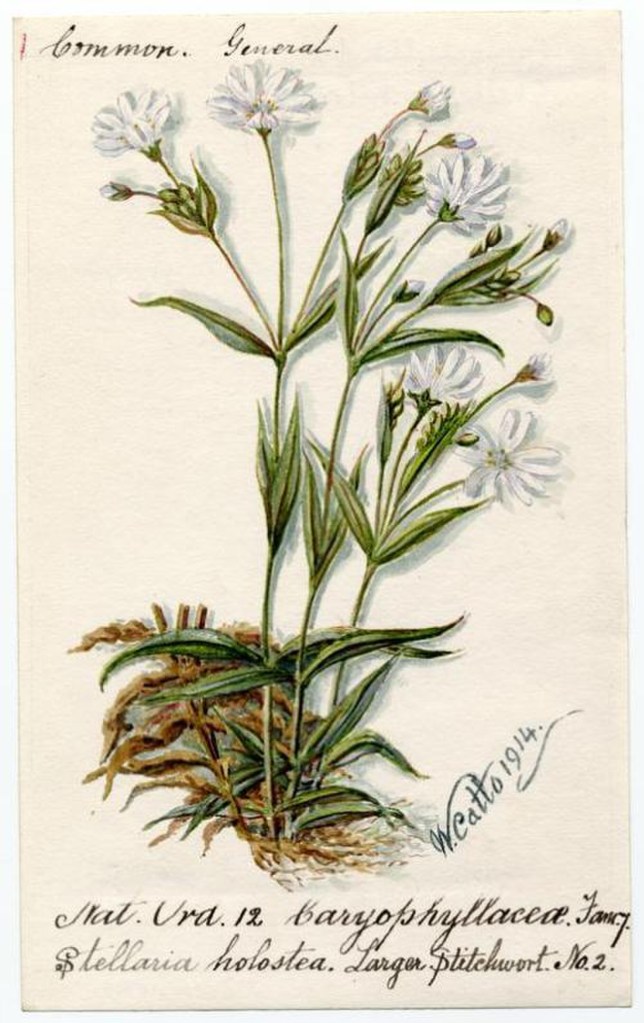

In this case I spotted a small patch of Greater Stitchwort hiding under a fragment of old and diverse hedgerow that counts Honeysuckle and Wild Plum amongst its showier denizens.

Stars, Cakes and Buttons

Stellaria holostea, commonly known as Greater Stitchwort or Star-of-Bethlehem, and less frequently as Wedding Cake or Daddy’s Shirt-buttons, is a charming perennial wildflower that graces woodlands, hedgerows, and grassy banks throughout the British Isles.

Its scientific name comes from the latin for star, stellar and the Greek word holosteon, which translates as ‘entire bone’, seemingly a reference to the brittleness of its weak stems.

It is, with its delicate white, star-shaped flowers and slender green stems, a fragile and unassuming plant, but welcome still, as its arrival heralds spring and brings beauty and ecological value to the habitats it grows within.

Carnations and Campions

Belonging to the Caryophyllaceae family, which includes other well-known plants like Carnations and Campions, Stitchwort typically grows to a height of 15 to 30cm. Its leaves are narrow, lance-shaped, and arranged in opposite pairs, with a smooth, slightly glossy texture, and the stems are notably square in cross-section, a common trait in the family.

The star-like flowers, blooming from April to June, are the plant’s most striking feature, each flower, about 2 cm in diameter, consisting of five white petals that are deeply notched giving, at a glance, the appearance of ten petals.

These petals surround a cluster of yellow stamens, creating a delicate contrast. The flowers are borne in loose clusters at the tops of the stems, opening, much like the similarly-coloured but unrelated Daisy, or ‘Day’s-eye’, fully in sunlight and closing in cloudy weather or at night, a characteristic termed ‘nyctinastic movement’.

Habitat and Distribution

Stitchwort thrives in temperate regions, particularly in the British Isles, prefering semi-shaded environments, such as deciduous woodlands, grassy verges or our hedgerow here, where it enjoys the dappled sunlight filtering through the Hawthorn leaves.

The plant favors well-drained, slightly acidic to neutral soils and is often found in areas with moderate disturbance, such as along footpaths or in clearings.

Its adaptability to various conditions has allowed it to spread widely, though it is less common in heavily urbanised or intensively farmed areas.

Small Yellow Underwing Panemeria tenebrata, S. holostea is a food-plant for its caterpillar

(Gail Hampshire)

Ecological Role

Greater Stitchwort plays a vital role in its ecosystem, its flowers provide nectar and pollen for early-spring pollinators, including bees, hoverflies and smaller butterflies like Orange Tips. The plant’s structure offers shelter for small insects, and its seeds, though not a primary food source, are occasionally consumed by birds and small mammals.

As a woodland species, Stellaria holostea contributes to the understory layer, helping to stabilise soil and prevent erosion in shaded areas. It often grows alongside other spring wildflowers like Bluebells, (Hyacinthoides non-scripta) and Primrose (Primula vulgaris), creating vibrant floral displays in spring.

Much like Bluebells its presence in an open area sometimes indicates that woodland once existed there, and in the location that I photographed these flowers it told me that this length of hedge has been established for quite a long time.

Cultural and Historical Significance

The name ‘Stitchwort’ is derived from the plant’s historical use in herbal medicine, where it was believed to relieve side stitches (sharp pains during exercise), the prefix ‘Greater’ distinguishes it from its smaller relative, Lesser Stitchwort, Stellaria graminea.

Its other commonly used name; ‘Star-of-Bethlehem’ likely originates from its celestial appearance, the Star of Bethlehem, or ‘Christmas Star’ guiding the three wise Magi to the newborn Jesus in Bethlehem, though it is unrelated to the more widely known garden-flower, Star of Bethlehem (Ornithogalum umbellatum).

In folklore, Stellaria holostea was sometimes associated with fairies and was thought to have protective qualities. Its delicate appearance made it a symbol of purity and simplicity in Victorian floriography, the language of flowers, and in some rural traditions, it was woven into garlands for spring festivals, celebrating the renewal of the season.

In some corners of the countryside, where the older ways and names of plants hold on, it is still known by the enchanting names of ‘Wedding cake’ and ‘Daddy’s shirt-buttons’.

These relate to its use, particularly in travelling communities (who are amongst the only people that still know these things) in boutonnière or buttonhole flower arrangements for weddings.

Indeed one of the only occasions a gentleman wears a buttonhole now is at a wedding yet once they were every-day accessories and considered as good luck charms, warding off evil spirits. I find this slightly contradictory though as Stitchwort, being one of the ‘fairy plants’ like Cuckooflower, will, when picked, incur the wrath of the fairies, who will punish you by way of thunderstorm, which is the last thing one wants on their wedding day!

A very rarely used name ‘Addersmeat’ is more curious, possibly hinting at its use in treating snakebites or its occasional growth in habitats where adders might be found, however, there is little evidence to support its efficacy against venom and I can’t find any other substantial reason for this name.

I do have a theory though, which is that as one punishment meted out by the fairyfolk upon those who dared to pick a flower beloved of them is supposedly to suffer the bite of an Adder, this might explain the name of Addersmeat, but I concede that it’s somewhat far-fetched!

(Bob Harvey)

Uses and Cultivation

Historically, S. holostea was used in herbal remedies, particularly for its supposed ability to soothe muscular pains and the aforesaid stitches.

Infusions or poultices made from the leaves and stems would be applied to ease discomfort, though modern science has not yet substantiated these claims. The plant is not widely used in contemporary herbalism due to its mild properties and the availability of more effective alternatives.

In gardening, Greater Stitchwort is valued as an ornamental plant for naturalistic or woodland-style wildlife-friendly gardens, its low-growing habit and early blooms also make it an excellent groundcover or companion for other shade-tolerant plants.

It is easy to cultivate, requiring minimal maintenance as long as it is planted in suitable conditions, and it is always best to choose native species over exotic introductions as the latter can spread beyond the confines of their gardens and out-compete our native species. S

The Art of Listening

By Veronica Aaronson

Hunt out wild flowers,

reach out, not to pick them

but as an offer of intimacy.

Stay open-hearted,

don’t put your ear

to the ground to listen

for sap or soil, instead

tune into the words

written between the lines –

visible in the way bluebell,

pink campion, stitchwort

offer up their secrets,

have made themselves

vulnerable against

pale and dark greens.

This is an offering –

last chance to hear

this moment’s prayer.

A B -H

(May 2025)