The Greater Butterfly Orchid, Platanthera chlorantha is a herbaceous perennial that typically grows to a height of 20 to 60 cm. It is easily recognised by its pair of broad, shiny, elliptical leaves at the base, with smaller, lanceolate leaves higher up the stem.

The plant’s flower spike, which blooms from May to July, bears 10 to 40 greenish-white flowers with a waxy appearance. Each flower has spreading sepals and petals that resemble the wings of a butterfly, giving the plant its evocative name. A long nectar spur extends from the back of each flower, and the plant emits a faint vanilla-like scent, particularly in the evening, to attract night-flying moths, its primary pollinators.

The key distinguishing feature between the Greater Butterfly Orchid and its close relative, the Lesser Butterfly Orchid (Platanthera bifolia), lies in the position of the pollinia (pollen sacs). In the Greater Butterfly Orchid, the pollinia are V-shaped, diverging at the base and converging at the tips, whereas in the Lesser, they are parallel, forming an ‘II’ shape.

However this subtle difference requires closer inspection for accurate identification.

(Gail Hampshire)

Habitat and Distribution

Greater Butterfly Orchids are found only in specific habitats, primarily unimproved grassland, hay meadows, and open broadleaved woodlands, most often on calcareous soils such as chalk or limestone. These orchids thrive in areas with minimal agricultural intervention, as they rely on stable, low-input management and a symbiotic relationship with soil fungi (mycorrhiza) for seed germination and growth.

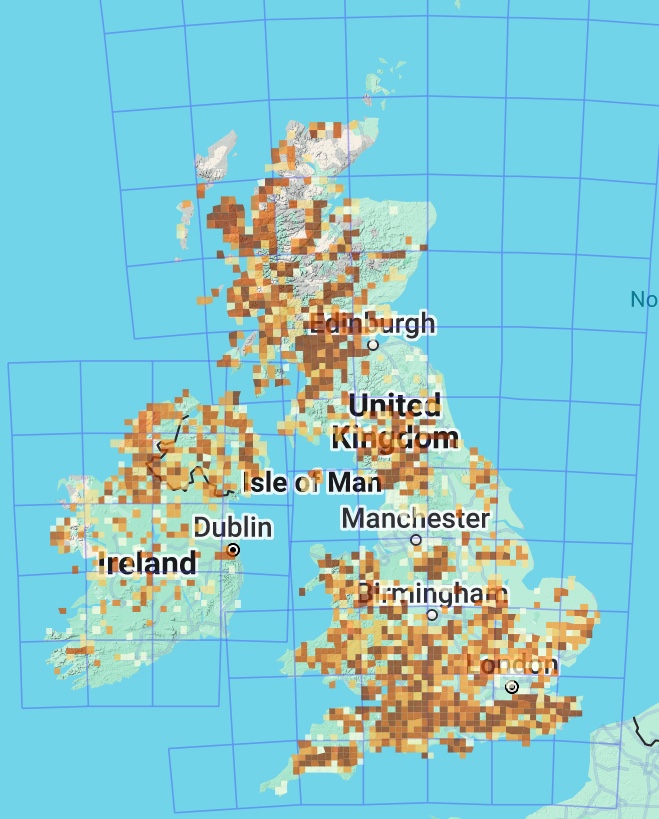

While more common in southern England, they are scarce here in the north, with populations few and far between, and only careful habitat management, such as traditional grazing and hay-cutting practices is helping the species hang on.

The orchid’s preference for undisturbed habitats makes it an indicator of ecologically significant sites with a long history of low-intensity land use. However populations are often small and vulnerable, particularly in the North of England, where such suitable habitats are limited.

(BSBI)

Conservation Challenges

As this Orchid faces significant conservation challenges across the UK it is classified as Near Threatened.

The primary threats include habitat loss due to agricultural intensification (a particular concern at the moment due to the abrupt ending of the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) scheme in March this year,) drainage of wet meadows, woodland disturbance, and intensive grazing.

These activities disrupt the delicate balance required for the orchid’s survival, particularly its dependence on mycorrhizal fungi, which are sensitive to fertilisers and fungicides.

In the North, upland populations are particularly at risk from overgrazing, which prevents the plants from flowering and setting seed. Conversely, undergrazing can lead to scrub encroachment and over-shading, which also threatens populations.

Climate change may also pose an additional risk, as extreme weather events, such as the prolonged dry weather we had this year (2025 as of writing) or colder springs, can disrupt the orchid’s pollination by moths and its symbiotic relationship with fungi.

Conservation efforts in the North of England focus on maintaining and restoring suitable habitats. Organisations like the Cumbria Wildlife Trust and Plantlife manage reserves with sympathetic practices, such as timed grazing and hay-cutting, to ensure orchids can thrive.

For instance, Plantlife’s reserves in North Wales, such as Caeau Tan y Bwlch, have served as models for habitat management that have been applied in northern England, where similar conditions exist.

Volunteer-led monitoring, such as annual orchid counts, also helps track population trends and inform management decisions to ensure the species’ survival, and we can see in the example below this is proving to be very helpful.

Conservation of P. chlorantha in Bowland

Using the conservation efforts for P. chlorantha in the Forest of Bowland as an example allows us understand the challenges better.

Here the focus is on protecting its sole known population, which consists of fewer than 20 flowering plants annually at one location. Key initiatives include:

- Annual Monitoring: Regular counts track the population, revealing threats like deer browsing, which damaged all flower spikes in 2013.

- Protective Measures: In 2014, 11 flower spikes were guarded to prevent browsing, allowing seed heads to ripen for natural regeneration.

- Seed Propagation: Four seed heads and soil samples were sent to a specialist nursery in 2014 to propagate seedlings, aiming to bolster the population.

- Habitat Management: The Friends of Bowland group maintains “Special Interest” (SI) verges, such as those at Newton and Tinklers Lane, by cutting and raking vegetation to preserve suitable grassland conditions.

- Nature Recovery Plan: The Forest of Bowland National Landscape’s plan (consulted in 2023) prioritises habitat restoration to support species like the Greater Butterfly Orchid, integrating with broader regional strategies.

These efforts aim to counter threats like habitat loss, grazing, and agricultural intensification, ensuring the orchid’s survival in its last Bowland stronghold.

You can read more about the conservation of rare and vulnerable plant species in Bowland here.

Orchid spotting

The delicate beauty and vulnerability of the Butterfly Orchid remind us of the importance of preserving traditional land management practices that have sustained these plants for centuries.

For those eager to spot them, the best time to look is during their flowering period in June and July, particularly in the early evening when their scent is strongest.

Nature reserves managed by Wildlife Trusts or designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) are ideal starting points, as they often list orchids as a protected feature. Always check with local trusts or reserve managers for access permissions and guided walks though, as some sites restrict access to protect delicate ecosystems.

And if you do find any specimens of this or any other rare plant species remember that it is illegal to pick or damage them, and please be careful about who you tell or posting about it on social media, as plant-theft is a real and growing threat to our natural heritage.

Jan Kops (1765–1849)

“It was my custom carefully to observe living plants on the spots where they grew, and not to make great collections of dried specimens; the latter are, no doubt, essential for the study of the structure and characters of plants, but it has frequently been the custom to collect specimens to such an extent, as to destroy the plant”.

“Many parties have also attempted to learn botany from dried specimens; for myself, I could never look upon a dried specimen with much satisfaction”.

“To obtain a true idea of a plant, let me see it alive and flourishing in the place where it grows, surrounded by all the conditions necessary for its growth”.

“In my eyes, dried specimens look like pallid corpses. Besides a dislike to dead plants, I did not like to take away and destroy living things, which might be

enjoyed by others as well as myself”.

Richard Buxton (1786–1865)

Richard Buxton was a self-taught Victorian naturalist and botanist from Prestwich. Born into poverty, he worked as a shoemaker while pursuing his passion for botany.

Largely self-educated, Buxton meticulously studied the flora of Manchester, culminating in his influential work, A Botanical Guide to the Flowering Plants, Ferns, Mosses, and Algae, Found Indigenous Within Sixteen Miles of Manchester (1849).

His keen observations and dedication to natural history earned him respect among contemporary botanists, despite his humble background. Buxton’s legacy highlights the contributions of working-class scientists to Victorian naturalism.

If you enjoyed this article you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting my site,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

June 2025