At first glance, Chitons (pronounced “Ki-ton”) don’t demand much attention; grey, unassuming and measuring only a few centimetres in length they usually go unnoticed by the casual passer-by or, at the least, are presumed to be limpets or a part of the rocks they live upon.

Yet, like a lot of our wildlife, if you notice one and take a moment to observe it you will find that they are in fact quite fascinating and worthy of your time.

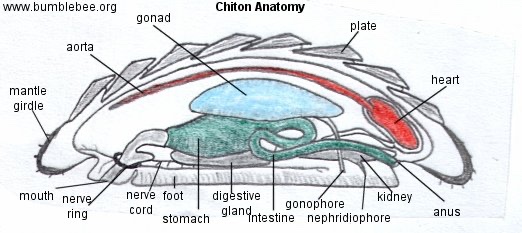

Here we dive into their biology to find out how these little creatures manage to survive in the harsh marine environs they call home.

Mollusc in Mail

Chitons, (also called “Mail-shells” or “Sea-cradles”) are members of the massive and multitudinous Mollusca tribe and live in that harshest of habitats; the intertidal zone, on the razor-edge between land and sea, so they need to protect themselves against a myriad of hazards.

To manage this they have evolved an impressive suit of armour, cladding their oval body in eight overlapping shell plates that resemble the segmented suits of steel knights wore in the days of yore.

These plates, embedded in a tough, leathery girdle, no only give the Chiton its characteristic “coat-of-mail” look but also lend it its name, which comes from the Ancient Greek χιτών (khitōn). This same Greek word is also the origin of ‘chitin,’ the substance insects and crustaceans grow their exoskeletons from, originally it referred to a full-length tunic worn by both men and women in ancient Greece.

This design hasn’t changed much in over 400 million years, making Chitons living relics of a time when life was just beginning to conquer the seas.

These shell-plates, made of calcium carbonate, allow them to flex and cling to irregular surfaces, while their muscular foot grips rocks with a suction-like force that defies the pounding waves of the seas.

When the tide recedes, you’ll often find Chitons tucked under rocks or crammed in crevices, their muted grey or brownish tones blend seamlessly with the surrounding stone and arming the creature with the shield of camouflage against foes like crabs and gulls.

Life in the Intertidal

In the intertidal zone, that dynamic frontier where land and sea wage a daily tug-of-war, the Chiton has found for itself an ideal niche, inhabiting sheltered spots like the undersides of rocks in rock-pools or the shadowed cracks of wave-cut platforms.

Here, it leads a slow, deliberate life, grazing on the thin film of microalgae and diatoms that coat the rocks, fed themselves by the constant influx of fresh food from the sea. It is however armed with a secret weapon, a radula, a rasping, tongue-like organ studded with magnetite-tipped teeth, one of nature’s hardest biological materials.

As the chiton nibbles and scrapes away, it plays a small but vital role in keeping algal growth in check, shaping the delicate balance of the intertidal ecosystem.

Unlike the flashy crabs or darting fish that share its habitat, Chitons are creatures of stealth and patience. They are mostly active at night or during high tide, gliding along on their broad foot, leaving faint mucous trails to mark their paths.

When the tide ebbs, they return to a ‘home scar’, a worn patch on the rock, often carved by the action of generations of Chitons, where they hunker down, minimising their exposure to drying winds and hungry beaks.

If dislodged, they will curl, much like woodlice or hedgehogs, into a tight ball, protecting their soft underbelly, a trick that’s served their kind for eons.

Aragonite Eyes

To sense threats Chitons have evolved a unique sensory system, (though they lack true eyes like those of vertebrates or cephalopods). This is comprised of specialised sensory structures called ‘aesthetes’ embedded in their shell plates, which include some light-sensitive features.

These “eyes,” primarily used to detect changes in light, pressure, and chemicals in their environment, are formed from a calcium carbonate based mineral called Aragonite (CaCO3), which, like magnetite is also a very hard biological substance. (Their cousin the Limpet produces the hardest, called geothite, in its teeth).

Those aesthetes specialised in sensing light are called Ocelli, from the Latin word ‘oculus’, meaning eye, but are not like the complex eyes me-and-you possess, instead being simple, lens-like structures that focus light onto photosensitive cells beneath.

They still serve their purpose remarkably well to detect light intensity and direction, helping them respond to shadows (e.g., from predators) or changes in light conditions, which is crucial for survival in their hard world. They cannot form detailed images as such but can sense light gradients, aiding in behaviors like seeking shade under rocks.

In most species aesthetes are distributed across all eight shell plates, with ocelli more concentrated in certain areas. The exact number and arrangement vary, but studies suggest some Chitons have hundreds to thousands of these tiny “eyes” across their shells.

Research indicates that ocelli can detect light wavelengths, potentially helping them differentiate between day and night or navigate tidal cycles, and that Chitons posses the ability to regenerate ocelli during shell repair, ensuring continued light sensitivity.

Seeking Chitons

Although found throughout British waters Chitons are particularly at home in the cooler waters of the North, thriving in the chilly, nutrient-rich currents of the North and Irish Seas, though they are very sensitive to pollution and habitat disturbance from coastal development.

Careless rock-turning by curious visitors can threaten local populations, so always replace stones as you found them to protect these unassuming mollusks.

There are 15 species of Chiton registered in UK waters, these are the most commonly encountered species here in Northwest England;

- The Grey Chiton Lepidochitona cinerea. This Chiton, our most common species, is usually a mottled grey pattern, although colours can alter. It looks a bit like a large woodlouse and grows up to 3 cm long. It is found under rocks in tidal pools or the lower tidal zone. Cinerea means ‘ash-coloured’, being the root of the word ‘cinders’.

(S. Rae)

- The Mottled Red Chiton Tonicella marmorea. This is a small species, up to 2 cm in length, with colorful, mottled red or pinkish plates, and is often found on algae-covered rocks, feeding on encrusting organisms. Marmorea means ‘marble-like’ describing the marbled pattern of its shell.

- The Spiny Chiton Acanthochitona crinita. Recognisable by its bristly girdle, this species reaches about 3 cm and inhabits lower intertidal and shallow subtidal zones on the underside of rocks and boulders, usually lightly embedded in sand or gravel, where it grazes on algae. Crinita means ‘hairy’.

- The smooth European Chiton or smooth mail-shell Callochiton septemvalvis. A less common but still notable species, up to 4cm long, with smooth, greyish-green plates, typically found in lower intertidal areas under pebbles and stones embedded in the sand. It can be identified by a band of cream most typically around the junctions of shell-plates (called valves by biologists) 1 to 2 and 7 to 8.

Chiton, a poem by Joan Swift

I discover the gift of a chiton left on my sidewalk

under an alien roof of ferns. This is Sunday morning and the world is pearled with mist. I remember its name is sea cradle and wonder

why it is so far from the sea and who cradled it here.

I lift it to my palm, eight overlapping bony plates, sand-color, silver,

the curve of a thumb edged with cilia like fur. Among the geraniums, a small anomaly, yet

down the back the steady keel of a boat. On the rock-strewn beach where the waves move pebbles in the hushed tones of mourners and the tide takes its salt kiss away,

I’ve looked for chitons alive, under rocks, the surf-splashed ledges, the sculptured furrows

of soft stone. Not to steal. To see how they cling, obdurate,

ferocious, to home.

They are not runners. This one flew by gull-beak or crow-

beak to my door with its story of loss.

Inside, all empty, the foot

and the meat devoured to show the opalescent plates’ interior, blue of the sky all sea cradles shun although it holds the moon and the sun that

rock them. This one rocks, dropping a little sand from its new sleep,

in the bend of my own lifeline. On the fourth plate from the dorsal end, a sprig of maroon seaweed,

still sea-wet, won’t let go.

Drawn by British naturalist George Brettingham Sowerby II (1812 – 26 July 1884)

If you enjoyed this article please consider showing your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting my site,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(July 2025)

One thought on “Northern Shores: Chitons, Armoured Knights of the Intertidal Realm”