As children me and my little sister spent most of our spare time outdoors, sometimes on our own but more often than not with friends, family, neighbours, our seemingly vast contingent of family friends or a chaotic combination of any and all of the above.

This was in the halcyon, care-free days of the 80s and 90s, before British society started degrading into its current insular state, and when parents weren’t quite so neurotic and risk-averse.

At this time of year (September as of writing) Bilberry season had just ended so we were usually looking forward to going out mushroom picking with our neighbours, their children and whoever else tagged along.

Foraging grounds were varied, and spread all over the county, but on a few occasions we drove up the A59 in their rusty old Austin Allegro from Fulwood to a farm that my parents friends had between Gisburn and Earby. I remember that they found it to be quite an arduous drive but well worth it for the fungal treasures that the farm’s fields bore at this time of year.

For these pastures gave forth fruit a little bit better than the usual Field mushrooms, something which was highly sought after by both our neighbours and parents, who both enjoyed cooking, as they produced prodigious numbers of the peculiar, white, fruits of the earth known as Giant Puffballs.

Giant Puffballs

Giant puffballs, Calvatia gigantea, are unmistakable once you know what to look for, making them an ideal entry point for novice fungi foragers. They appear as a large, spherical or slightly flattened ball, pure white when young and fresh, with a smooth, leathery skin that resembles fine suede.

Sizes typically range from 20 to 50cm in diameter, though I have heard of specimens of up to 80 centimetres being found, enough to feed a family!

Inside, the flesh should be uniformly white and firm, like a dense marshmallow or fresh mozzarella. This is crucial for edibility; if the interior shows any yellowing, browning, or the beginnings of spore formation (turning into a powdery mass), it’s past its prime and should be left alone.

You must avoid confusion with immature amanitas though, like the deadly destroying angel, which have gills and stems hidden in an egg-like volva, puffballs lack these entirely, of course our neighbours knew this very well for me and my sister are still here today!

Here in the North West they’re most common from late summer to early autumn, often popping up after warm rains in grassy fields.

A word of caution though; always double-check with a field guide or app, and if in doubt, leave it out. Local mycological societies often run forays where experts can confirm your finds.

(Martin Jones)

Puffball Pastures

Thriving in nutrient-rich, open grasslands, Giant Puffballs are saprotrophic, feeding on decaying organic matter in the soil, which explains their preference for old meadows, golf courses, or even roadside verges, wherever the ground is undisturbed. It’s been noted that they like areas once used for medieval strip farming, which hints at how human activity has shaped their haunts.

While widespread across the British isles, the North West offers prime puffball grounds due to our mild, damp climate. They are frequently found in Cumbria’s Eden Valley or Lancashire’s Ribble Valley, where the rich, wet soils provide ideal conditions.

Climate change may be influencing their range, as warmer, wetter autumns could extend their season, but habitat loss from intensive agriculture poses a bigger threat. Conservation efforts, like those by the Wildlife Trusts in the region, emphasise leaving some specimens to spore and propagate.

Puffball Power

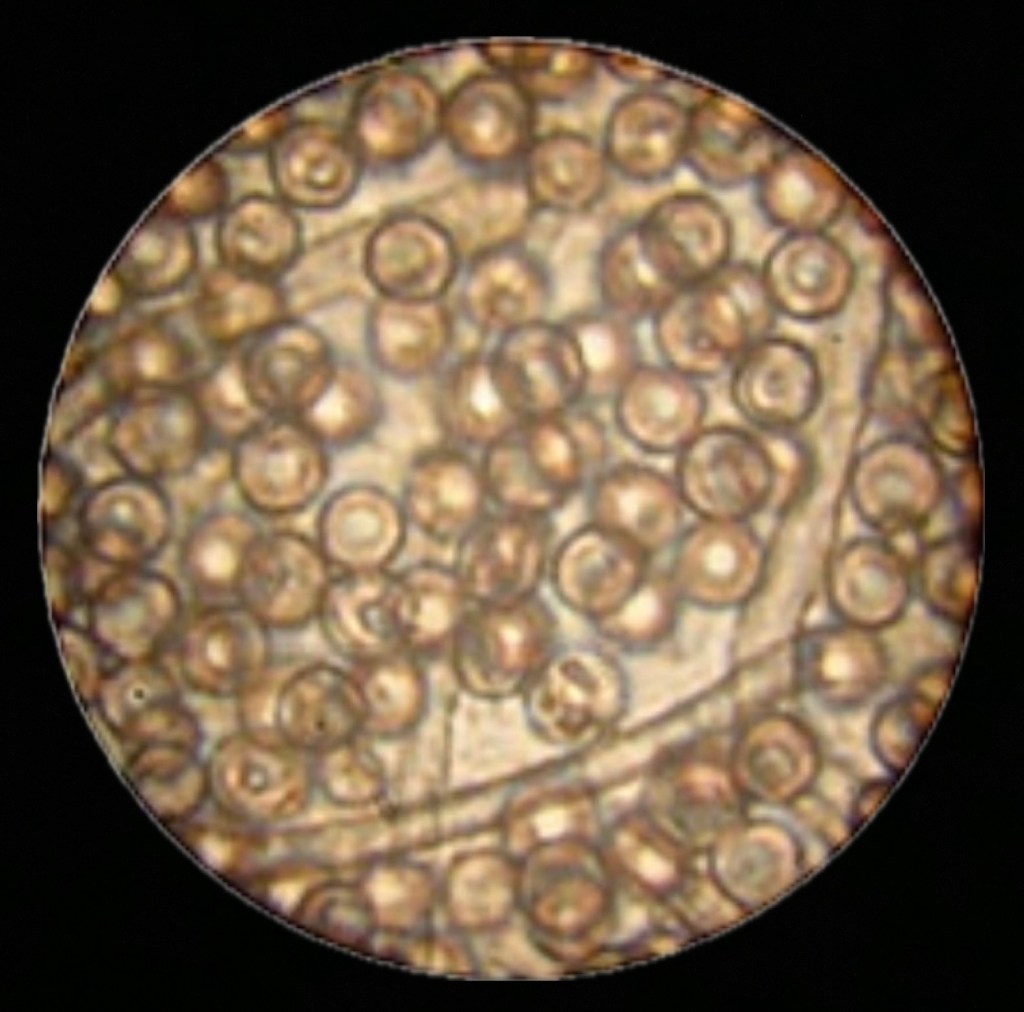

The life-cycle of a Puffball is a natural wonder; starting as microscopic mycelium threads underground, it balloons into the fruiting body we see, filled with trillions of spores. When mature, the outer skin cracks, releasing a cloud of brownish spores in a puff (hence the name) which are dispersed by wind, rain, or passing animals.

Ecologically, the Giant Puffball, a member of the 160-species strong Lycoperdaceae family, plays a vital role in nutrient cycling, breaking down dead plant material and returning essential elements to the soil. They greatly support biodiversity too; insects like beetles and flies lay eggs inside, and small mammals may nibble them, aiding spore spread.

one spore = 1/200 mm

Folklore and Folk Medecine

Folklore attaches great importance to the Puffball, in Celtic traditions, they were seen as “fairy bread” or omens of good fortune, perhaps due to their sudden, ethereal appearance overnight. Historically, during the Industrial Revolution, Puffballs were used by herbalists as styptic agents to staunch wounds, their spore powder acting like a natural bandage.

In Victorian times naturalists documented their use in folk medicine, noting that their spores were smoked to treat bee stings or applied as poultices for skin ailments.

Today, they’re celebrated more for their edibility than anything else. When young and white inside, they’re a gourmet treat: mild, nutty, and versatile, with a texture akin to tofu or eggplant, although I feel that fewer people pick them nowadays, and modern-day kids are more likely to play football with them than take them home!

For those seeking to forage for Puffballs please pick responsibly, take only what you need, and always with landowner permission, and in protected areas like AONBs or SSSIs it is probably best to avoid picking them at all or risk fines.

A Simple Puffball Recipe

If you’ve foraged a fresh Giant Puffball (or sourced one from a trusted supplier), here’s a recipe that’s straightforward and brings out its subtle flavour.

It serves 2 to 4 as a side or main, and pairs well with local ingredients like Lancashire cheese.

For a wine pairing I’d suggest something light like an un-oaked Chardonnay or Sauvignon Blanc, D Byrne & Co will recommend the best bottle they have.

For music (I do a music recommendation for every recipe) it has to be It’s mushroom season by Bob Brown.

Ingredients:

• 1 medium giant puffball sliced into 1 to 2cm thick ‘steaks’

• 2 tbsp of olive oil or butter

• 2 cloves of garlic

• Fresh herbs; Thyme, Rosemary, or Sage

• Salt and pepper to taste

• Lemon wedge for serving

Method:

Preparation; Slice the puffball horizontally into steaks, discarding any with discolouration. Pat dry with a clean cloth, there’s no need to peel the skin if it’s clean

Cooking; Heat the oil or butter in a large frying pan over medium heat. Add the garlic if using, and sauté for 1 minute until fragrant

Fry the Steaks; Place the puffball slices in the pan without overcrowding. Cook for 4 to 5 minutes per side until golden brown and crunchy on the outside, soft in the middle. Sprinkle with chopped herbs, salt, and pepper halfway through

Serve: Drizzle with lemon juice for what chefs call “brightness”, and enjoy as a vegetarian ‘steak’ with a salad of greens, we often buy ours from the veg stalls at Clitheroe Market. It also works very well served on sourdough bread.

Safety Note; Only consume if you’re 100% sure of identification, allergic reactions are rare but possible; so start with a small amount. Cooking destroys any potential toxins in mature specimens, but always err on fresh.

To learn more about foraging for fungi you can look at my piece about Mushroom Picking from last year or, even better, join a guided walk with the British Mycological Society’s local branch, here is the one for the Northwest; the North West Fungus Group.

Happy foraging!

If you enjoyed this article please consider showing your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Sep 2025)

This is a great reminder of how simple and grounding foraging can be when it’s done with patience and respect. Puffballs are such an inviting entry point into wild mushrooms, and I appreciate how clearly you emphasize positive identification and timing. There’s something quietly satisfying about finding them at just the right moment, before they turn, and knowing you’re participating in an old seasonal rhythm. Pieces like this make the practice feel less intimidating and more like a conversation with the landscape.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank-you, that’s what I set out to achieve with this piece so I’m very happy that it worked, it helps that I have very clear memories of going out picking as well

LikeLiked by 1 person