A look at one of our Most Common Foliose Lichens, with some Notes about Uses for Measuring Air Pollution and Chemical ‘K, C and Pd Identification Tests

Flavoparmelia comes from the latin words flavus, meaning ‘yellow’, and parma, meaning ‘shield’, caperata is latin for ‘wrinkled’

Flavoparmelia caperata, widely known as the Common Greenshield Lichen, is one of the most recognisable foliose (leaf-like) lichens in the British Isles. With its large, rounded, pale yellowish-green lobes it is hard to confuse with anything else once you know what to look for.

In the rainy, relatively clean air of the Northwest it remains a frequent and often abundant species on deciduous trees, worked timber and nutrient-enriched rocks.

Ecology and Preferred Habitat

In Northwest England, F. caperata is overwhelmingly a corticolous (bark-dwelling) species, though it occasionally colonises siliceous rocks (mainly sandstone) near the coast or on upland walls where bird droppings provide extra nutrients. It shows a marked preference for well-lit, moderately nutrient-rich bark and is therefore common on:

- Ash (Fraxinus excelsior), Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), Elder (Sambucus nigra), Willow (Salix spp.) and Oak (Quercus robur/petraea)

- Isolated mature trees in farmland and along hedgerows

- Old orchard trees and churchyard Lime and Yew

- Worked timber: fence posts, old gate posts, and even wooden benches if they are not treated with preservatives

- Occasionally on mossy boulders and sandstone walls in coastal or lowland areas (e.g. the Arnside–Silverdale area, the Cheshire sandstone ridge, or the Lancashire coast)

It is notably less frequent on highly acidic bark such as Birch or Conifers, and it disappears quickly where stem-flow is heavily enriched with ammonia (e.g. directly beneath regular bird roosts). This makes it a classic “sub-neutral bark” species in the British lichen flora.

Sensitivity to air pollution

F. caperata is moderately sensitive to sulphur dioxide (SO₂) and highly sensitive to ammonia (NH₃). During the peak of industrial coal burning in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was virtually eliminated from much of urban Manchester, Liverpool, Salford and the Lancashire mill towns. Old records from the 1950s and 1960s show it surviving only in the cleaner western fringes (Formby pinewoods, the Fylde coast) and in the Lake District.

The dramatic reduction in SO₂ emissions since the Clean Air Acts and the switch from coal to gas has allowed a spectacular recolonisation. By the mid-1990s it was back in central Manchester parks (e.g. Heaton Park, Philips Park) and is now frequent even in Liverpool city centre on Lime and Plane trees.

However, the rise in agricultural ammonia emissions since the 1980s has created a new constraint; in intensively farmed lowland Cheshire and south Lancashire it is often scarce on isolated field trees that are bathed in ammonia-rich air, whereas it remains luxuriant on the same tree species in urban parks or on the windward (western) side of the Lake District where ammonia deposition is lower. (Read more about the use of Lichen for assessing the effects of air pollution here)

Identification tips

- Upper surface: pale yellowish green (never grey), smooth when dry, conspicuously wrinkled or ridged when wet

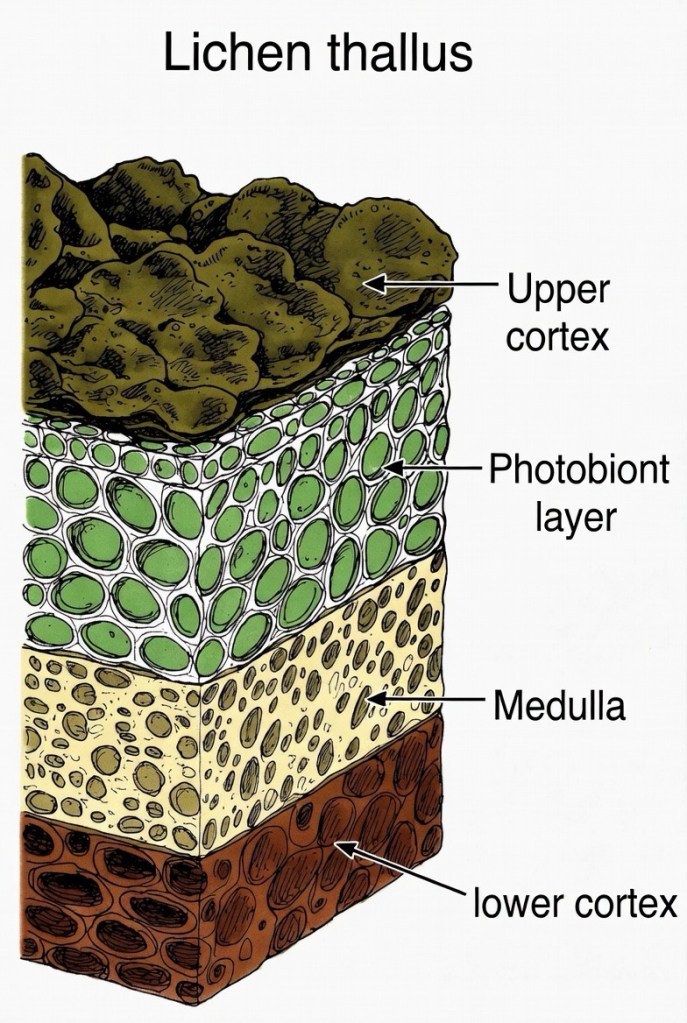

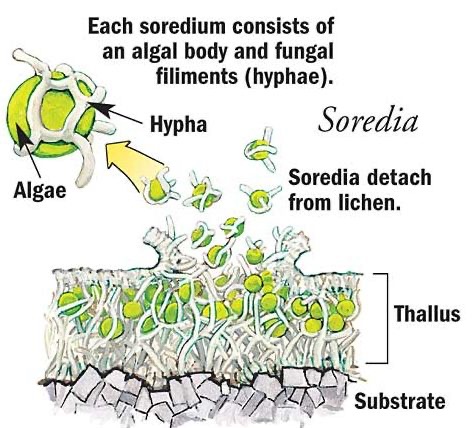

- Lobes: broad (5 to 20mm), rounded, often overlapping, margins usually bearing bright, lime-green granular soredia in crescent-shaped soralia (see diagram below)

- Underside: black in the centre, fading to brown or pale at the edges

- Testing with Pd/K+ yellow leads to a red reaction (fumarprotocetraric acid in the medulla, visible if you scratch a lobe with a scalpel and apply KOH followed by paraffin, see chapter below for a brief explanation of how lichen tests work)

Very similar species (Parmotrema perlatum, Punctelia jeckeri, P. subrudecta) are generally greyer and lack the intense yellowish-green colour.

K, C and Pd tests

There are three classic spot tests commonly used to identify lichens in the field: the K, C, and Pd (or “yellow”) tests. Pd is an abbreviation of para-phenylenediamine and called the “yellow test” because the reagent is a bright yellow/orange liquid.

How the Pd test works

- Reagent: A 1% alcoholic solution of para-phenylenediamine (Pd), sometimes with a little sodium sulfite added as a stabiliser (Pd is toxic over a long period of exposure)

- What it detects: Certain lichen substances, especially dibenzofurans like usnic acid (found in Usnea lichens) that undergo oxidation in the presence of Pd

- Reaction mechanism: Para-phenylenediamine is a strong reducing agent. When it comes into contact with specific lichen acids that can act as electron acceptors, it rapidly oxidises. This oxidation produces vivid coloured quinone-like compounds.

- Typical colours:

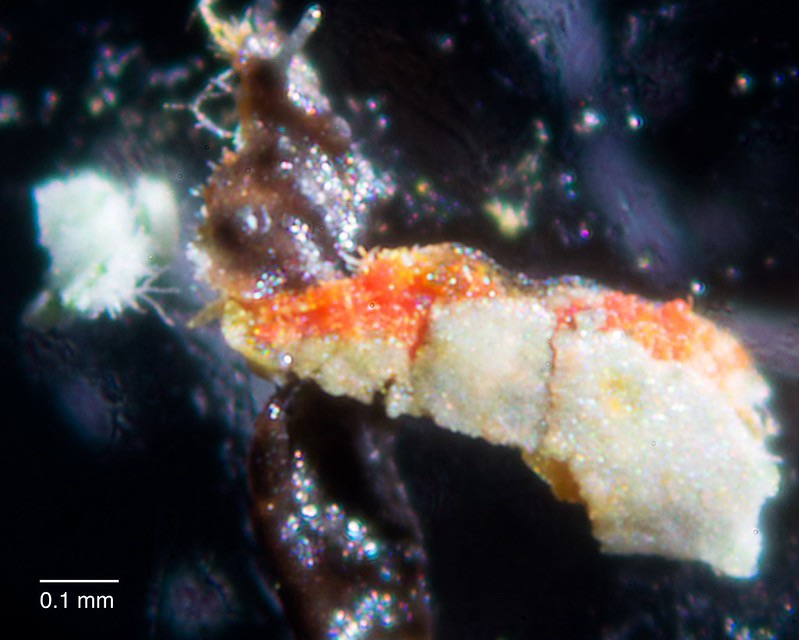

- Bright red is a very common positive reaction (e.g., with fumarprotocetraric acid in many Parmelia species or stictic acid in Pertusaria)

- Orange-red, purple-red, or blood-red are also seen

- Some substances give green or brownish reactions

- No color change = negative

How to perform the test

- Place a tiny drop of Pd solution directly on the lichen cortex or medulla (medulla is usually more reliable).

- Wait 10 to 60 seconds.

- Observe immediate or slowly developing colour change in the tested area.

The other two common tests

- K test: 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH). Detects substances that turn yellow/red in alkali (e.g., anthraquinones) or release coloured pigments.

- C test: Household bleach (sodium hypochlorite, Ca(OCl)₂). Detects substances that react with hypochlorite to give red/orange colours (especially certain depsidones).

(rexp2)

Notable sites in Northwest England

- Cumbria: abundant throughout the Lake District on Ash and Oak at low to mid elevations; you can see huge specimens on veteran trees at Borrowdale Yews NNR and on mossy rocks at Whitbarrow Scar.

- Lancashire: very common on the Fylde coast dunes on Elder and Willow; recolonising central Preston and Lancaster.

- Merseyside: now frequent in Liverpool parks (Sefton Park, Calderstones) and along the Mersey estuary on wind-clipped trees.

- Greater Manchester: large patches in Dunham Massey deer park, Heaton Park and along the Irwell valley.

- Cheshire: widespread on the Mid-Cheshire sandstone ridge (Delamere Forest, Frodsham Hill) and on old orchard trees, but scarce in the dairy-farming plains to the south.

Victorian lichenologists called it ‘Parmelia perlata caperata’ and considered it one of the showiest British species. The famous 19th-century collector William Joshua collected magnificent specimens from Rivington Pike (Lancashire) that are still in the Manchester Museum herbarium.

Its recovery over the last forty years is one of the clearest biological indicators that urban air quality in Northwest England has improved dramatically since the dark days of the Industrial Revolution.

An Ode to Lichen, by David Gate

Grey or silver Green or black

Terracotta

Red or yellow

Through the drought

The heat, the freeze

Where nothing lives

Where nothing breathes

Yet they do live

They do survive

And with slight surprise

They come to thrive

A miracle creature

Neither plant nor animal

But something else entirely.

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves