Hunting for the Common Snipe in Northwest England

If you’ve ever stood in the reeds of Chat Moss, the wet sheep-pastures of the Ribble estuary, the peat-bogs of Bowland or the rushy fields around Martin Mere on a still April evening, you might have heard a weird, somewhat spooky, sound that you couldn’t quite put your finger on; a bleating, almost goat-like humming that seemed to come from the sky itself, and you may have wondered what made it.

This is the sound of a male Common Snipe “drumming” and is one of the eeriest wildlife spectacles our countryside has to offer.

(Hobbyfotowiki)

A Master of Dodging and Disguise

The Common Snipe, Gallinago gallinago, is a plump, cryptically patterned wader with an absurdly long bill (often longer than its own body), enormous dark eyes set far back on the head, and a coat of mottled browns, buffs and blacks that makes it vanish against dead rushes and peat.

When flushed, it explodes from virtually under your feet with a rasping “scraaape!”at a speed calculated to be over 40mph, and zig-zags or “jinks” away low over the rushes, it’s the origin of the word “sniper”, because only the very best shot can hit one.

Snipe used to be commonly shot for the table, the traditional way to prepare them being to roast them whole without cleaning them out (gutting them), but thankfully those days are largely gone and it is now regarded as a target fit only for the best shots, and is therefore a source of pride for the gamekeeper or landowner who has cared for his land well enough to produce them.

Fewer and fewer shoots are allowing them to be shot nowadays, or ban them from being shot until September at the earliest, as land managers become increasingly conscious of the need to conserve our native wildlife, though some shoots may hold a couple of walked-up Snipe days in a season if their ground holds a decent number of the birds.

The shooting community reason that keeping them on the quarry list will keep the incentive to maintain their habitat and will reverse the decline in numbers that this species has suffered in recent decades.

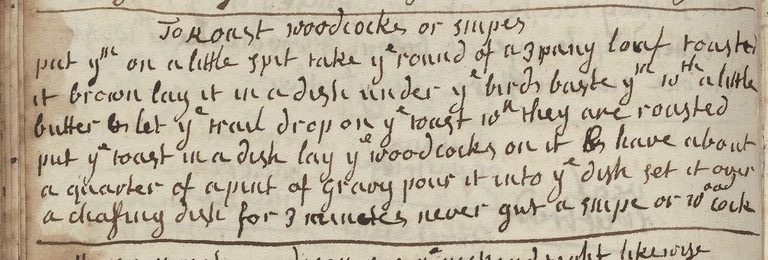

Snipe recipe from c1740;

To Roast woodocks or snipes, put them on a little spit take the round of a 3 pany loaf toast[ed] it brown lay it in a dish under the birds baste them with a little butter & let the trail drop on the toast when they are roasted put the toast in a dish lay the woodcocks on it & have about a quarter of a pint of gravy pour it into the dish set it over a chafing dish for 3 minetes never gut a snipe or woodcock.

How to Encourage Snipe

Effective land management for Snipe focuses on maintaining or restoring wet features and suitable vegetation structure to support breeding, feeding, and nesting.

Key Practices

Maintaining high water levels

Preventing drainage by blocking ditches/grips and avoiding new drains. This keeps soil soft for probing and creates shallow wet flushes or pools, essential for feeding and chick survival.

Grazing management

Using light to moderate grazing (preferably cattle) to create a mosaic of short and taller vegetation (10 to 30 cm tussocks for nesting cover). Avoiding overgrazing, which compacts soil, or undergrazing, which leads to dense rank growth.

Create wet features

Digging shallow scrapes or foot drains to hold surface water, providing feeding areas even in drier periods.

Rush and vegetation control

Periodically cutting or managing rushes to prevent dominance while retaining patches for cover.

Habitat mosaics

Promoting varied structure with rushes interspersed with open muddy areas and short grass.

A Snipe can see 360° around and 180° above

(Mike Pennington)

Where to Find Them in the North West

- Chat Moss & Astley Moss (Greater Manchester/Salford) one of the strongest breeding populations in lowland England.

- Ribble Marshes & Hesketh Out Marsh (Lancashire) huge winter flocks, sometimes several hundred strong.

- Forest of Bowland (Lancashire/North Yorkshire) they are often flushed from the boggier parts of the fells and from the numerous pools found on the tops, Stocks reservoir is a good place to spot them too.

- Martin Mere WWT & the surrounding farmland (West Lancashire) classic “snipe fields” that flood in winter.

- Leighton Moss RSPB (Silverdale, Cumbria/Lancashire border) listen for drumming males over the reedbeds in spring.

- The Solway Firth marshes (Cumbria) internationally important wintering numbers.

- Winmarleigh Moss & Cockerham Moss (Lancashire) traditional breeding sites still holding on.

The Extraordinary Drumming Display

In spring and early summer, male snipe perform their “drumming” or “bleating” display flight, with the bird climbing high, then diving steeply with its outer tail feathers spread. The wind rushing across these stiffened feathers is what produces the eerie vibrating hum, nature’s own musical instrument.

On a calm evening in the right place you can sometimes hear half a dozen males drumming at once, a sound as characteristic of our wetlands as the call of the Curlew. One of the most magical experiences I ever had was a dusk-time walk along a farm-track on Rathlin Island off the north coast of Ireland where I was mesmerised by the spectacle of at least half a dozen Snipe drumming with a huge, yellow full moon and the Atlantic ocean as a backdrop!

(Mike Pennington)

The Snipe Hunt

“What does a snipe look like?”

“It’s got red, glowing eyes,

long, crooked teeth, a claw…”

“and a tail with another claw on the end.”

In one of my favourite King of the Hill episodes; The order of the Straight Arrow, episode 3, young Bobby Hill is made an initiate of the Straight Arrows and is sent on a ‘Snipe Hunt’ to prove his mettle, a Snipe hunt being a practical joke originating in North America.

The earliest documented references to this tradition date to the 1840s and it is thought to have emerged as a type of fool’s errand or wild-goose chase, where experienced campers or hunters tricked newcomers into pursuing an imaginary creature (often described variably as a bird-like animal) using absurd methods, like holding a bag open in the dark while others would “drive” it toward them.

The prank’s plausibility stems from the fact that the real-life Snipe is notoriously difficult to hunt due to its camouflaged plumage and erratic flight. Over time, as fewer people hunted real Snipes, the fictional version dominated, turning it into a classic hazing ritual.

It gained popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially at summer camps, Boy Scout outings, and rural gatherings, serving as a harmless rite of passage. Some sources suggest influences from older European fool’s errands, but the specific “Snipe hunt” form is distinctly American.

(Mike Pennington)

Ups and Downs

Snipe suffered catastrophic declines in the 20th century as virtually all of our lowland bogs and wet meadows were drained for agriculture, as a result they became extinct as breeding birds in many English counties. The North West, however, retained just enough wet corners; the mosslands, the Ribble floodplain, the grazing marshes of the Wyre and Lune, for small populations to cling on.

Recent decades have brought hope. Agri-environment schemes paying farmers to keep fields wet, re-wetting of former peat workings, and reserves like Martin Mere and Leighton Moss have all helped. Breeding Snipe have returned to parts of Greater Manchester (notably the Salford Mosses) for the first time in living memory, and winter flocks on the Ribble regularly top 1,000 birds.

How to See (and Hear) Them

- Visit wet rushy pasture or flood meadows at dawn or dusk in April to June for the best chance of drumming, make sure you are away from traffic noise to stand the best chance and sit still to listen for a while.

- In winter, look for them feeding at the edges of splashes and ponds, the long bill probing deep into the mud like a sewing-machine needle.

- A sudden flush of a single bird from almost under your boots is almost guaranteed at some point, however if you own a dog which is descended from a hunting breed, especially a pointer of some sort, it is likely they will point them or flush them before you. Of course it goes without saying that your dog should be on a lead if in the kinds of habitat Snipe like to frequent.

The Snipe remains as one of those birds that reminds us how rich, strange and noisy our wetlands used to be and, with care, can be again. Next time you’re out on a moss or marsh, stand still for a moment when the light fades. If the sky starts to hum and bleat with invisible goats, you’ll know the Snipe are still holding the fort.

Plate XXXI from The game birds and wild fowl of the British Islands, 1900, Dixon, Charles; Whymper & Charles

Snipe

A poem by Ted Hughes from his 1983 collection ‘River’

You are soaked with the cold rain –

like a pelt in tanning liquor.

The moor’s swollen waterbelly swags and quivers, ready to burst at a step.

Suddenly

Some scrap of dried fabric rips itself up from the marsh-quake, scattering.

A soft explosion of twilight in the eyes, with spinning fragment somewhere.

Nearly lost, wing flash stab-trying escape routes,

wincing from each,

ducking under and flinging up over –

bowed head, jockey shoulders climbing headlong as if hurled downwards –

a mote in the watery eye of the moor –

hits cloud and skis down the far rain wall,

slashes a wet rent in the rain-duck twisting out sideways –

rushes his alarm back to the ice age.

The downpour helmet tightens on your skull, riddling the pools,

washing the standing stones and fallen shales

with empty nightfall.

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Dec 2025)