Foreword

First published on substack this article refers to a proposed development which would affect the counties of Cambridgeshire and Suffolk, a part of the country clearly far from my usual stomping grounds in Northwest England.

Therefore you would be justified in asking why I write about this here, on Northwest nature and history.

To this, dear reader, I reply so;

This proposal, as demonstrated by its official title: Forest City 1, is intended to be one of several such developments situated throughout the United Kingdom and, as discussed here, could, if it goes ahead, have severe ramifications for the ecological, historical and social fabric of whichever area they may eventually be sited.

This could be the Northwest, or even that which you sit reading this in now.

Forest City 1

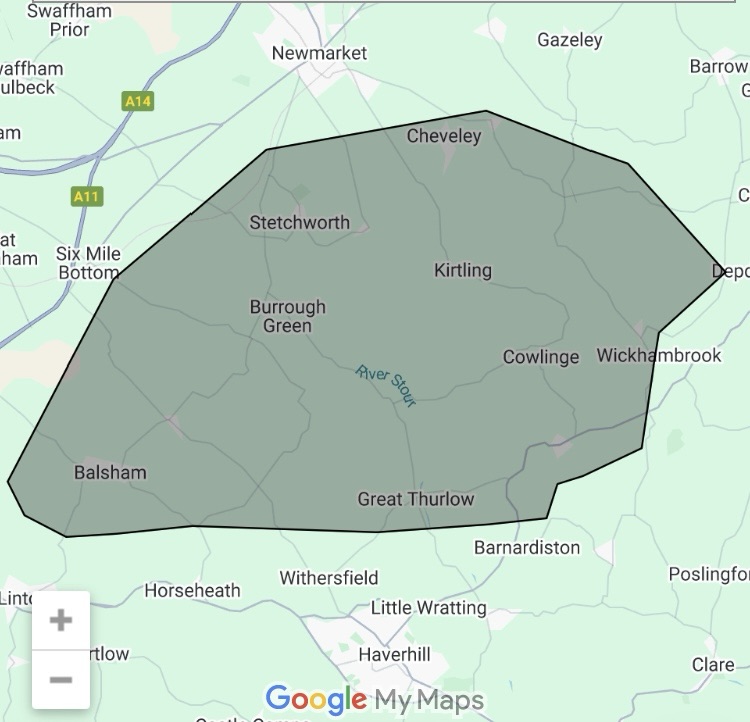

Forest City 1 is a recently proposed city development planned for agricultural land on the Cambridgeshire-Suffolk border. A private initiative its purported aims are to address the housing crisis in the UK and stimulate economic growth.

Here I dissect these proposals, uncover the flaws within them that may cause irreparable harm to our environment and society, and suggest some viable alternatives and solutions.

Whether Britain’s housing crisis is real or, as many posit, invented by the media and over-egged by developers to justify unchecked building (after all we have over 1 million empty homes we could fill before having to build new ones) is a discussion to be had at another time, what certainly isn’t real is the idea that concreting over 45,000 acres of prime East Anglian farmland to create a privately masterminded “forest city” for a million people will fix it.

The brainchild of former Guardian journalist turned housing evangelist Shiv Malik, and tech entrepreneur Joseph Reeve, Forest City is being sold with glossy AI-generated renders, celebrity endorsements and the breathless claim that it will be “Britain’s first new city in 50 years.”

In reality, it is an astonishingly hubristic, environmentally reckless and financially opaque scheme that repeats almost every mistake of the grand urban follies that came before it, from the brutalist new towns of the 1960s to the ghost skyscrapers of Malaysia’s failed Forest City.

Wrapped in impressive-sounding yet ultimately vacuous phrases like “national renewal,” “permanent affordability” and “biodiversity repair,” the proposal actually asks the country to gamble tens of billions of pounds and irreplaceable agricultural land on an untested Community Land Trust model scaled to absurd proportions, all fast-tracked through special Development Corporation powers that deliberately sidestep democratic planning.

Its backers insist they need only “permission, not subsidy,” yet the small print reveals a project that would depend on massive public infrastructure commitments, captive residents locked into resale restrictions, and the heroic assumption that Cambridge’s tech boom will magically absorb a population the size of Birmingham.

Far from being a bold answer to policy failure, Forest City 1 is the ultimate symptom of it: an elite-driven spectacle that mistakes scale for vision, green branding for sustainability, and crowd-sourced pledges for genuine demand.

The Bumph

According to ‘the bumph’, Forest City 1 is a response to what its creators call a “policy failure” rather than an inevitable housing crunch. Spanning 45,000 acres of agricultural land between Haverhill and Newmarket on the Suffolk-Cambridgeshire border, the city would blend “gentle density” urbanism, think six-story buildings reminiscent of Paris or Barcelona, with eco-friendly modular wooden construction. Homes would be Passivhaus-standard, all-electric townhouses priced at £350,000 for a four-bedroom family unit, roughly 60% below Cambridge averages, due to a Community Land Trust (CLT) model that keeps land community-owned and resale prices capped.

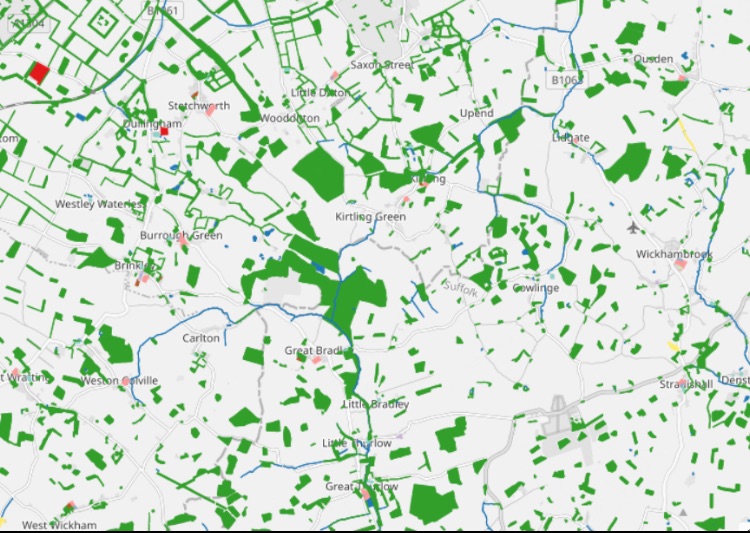

The pitch is seductive: infrastructure is baked in from day one, including schools, hospitals, trams, and parks; businesses lured by proximity to Cambridge’s “innovation capital”; and nature not as an add-on but rather the theme of the whole scheme. Proponents envision 12,000 acres of new deciduous forest linking existing ancient woodlands, creating a “nature reserve where people live.” It’s a place for “ambitious families,” with 30% of initial residents selected on merit; entrepreneurs, educators, and innovators, to seed a thriving community. Powered by solar power and 6G-ready, the city would prioritise pedestrians over cars, with walkable hubs where children “run free”.

The spiel pushes it as “national renewal” rather than mere housing. As Dame Patricia Hewitt, former Labour Secretary of State, puts it: “Building a new city may seem outrageously audacious but it’s part of what will make national renewal real.” Professor Tim Leunig, ex-advisor to Conservative chancellors, echoed this, praising the CLT for enabling Industrial Revolution-style rapid builds. The roadmap is startup-fast: Phase 1 proves demand via pledges (already nearing 800 signatories); later phases secure legislation and ground is to be broken by the end of the parliamentary term.

At £100 billion, it’s privately funded, demanding only “permission, not subsidy” through a new Development Corporation.

The Backers

The momentum Forest City 1 has gathered so far stems from a coalition of unlikely allies including intergenerational thinkers, political heavyweights, and growth evangelists. At the forefront is Shiv Malik, a 44-year-old former Guardian investigative journalist turned author and investor. Malik, who co-founded the Intergenerational Foundation, a think tank focused on millennial and “Gen-Z economic woes” (I had to look up the meaning of ‘Gen Z’ apparently it refers to people born between 1997 and 2012) has long critiqued Britain’s “managed decline”.

His 2023 book The Big Shift argued for “radical infrastructure reboots” to “avert generational conflict,” ideas that crystallised into Forest City during the pandemic lockdowns. “Britain stopped believing the future could be better than the past,” Malik writes on the project’s site. “We’re here to prove that wrong.” A ‘YIMBY’ (counter-phrase to the equally childish-sounding acronym ‘NIMBY’ meaning Not In My Backyard) advocate and advisor to the YIMBY Alliance, Malik, who capitalises enormously on his charisma, shone like a true salesman should at the O2 launch in November 2025, where he rallied 1,200 attendees with visions of wooden skyscrapers and tree-lined avenues.

Malik’s co-founder is Joseph (Joe) Reeve, a serial entrepreneur and co-founder of Looking for Growth (LFG), a grassroots campaign that’s pressured Labour on planning reforms. Reeve, whose background includes tech startups and policy lobbying, brings the “move fast and build things” ethos, emphasising private-sector speed over Whitehall inertia. While LFG shares Forest City’s growth zeal, boasting supporters from Green Party activists to right-wing think tanks, the project operates as a distinct entity under the nascent Albion City Development Corporation (ACDC).

The advisory roster appears to add some bipartisan heft: Hewitt champions people-focused partnerships; Leunig touts economic multipliers; Angus Hanton of the Intergenerational Foundation pushes long-termism; and Tom Chance of the CLT Network eyes scalable affordability. This cross-spectrum backing, spanning Labour veterans, Tory advisors, and eco-campaigners, lends a front of credibility, and the nearly 800 pledges signals some appeal yet it’s a top-down affair, reliant on Malik and Reeve’s lobbying to secure parliamentary buy-in, raising questions about whether this elite-driven vision truly represents “communities that feel like home”.

(John Sutton)

Critical Reception: When Audacity Meets Skepticism

The proposals for Forest City have ignited a firestorm of debate, with supporters hailing it as a “complete reimagining” of British urbanism and detractors branding it “bonkers” and “ridiculous.” On the positive side, it’s tapped into the YIMBY fervor, amplified by media like The Guardian (remember that Malik previously worked for them), which in late November 2025 explored how it could align with Labour’s 1.5 million homes target.

Pledges have passed 700, drawing interest from London and Cambridge residents weary of sky-high rents. Online there is a mix of cautious optimism and ridicule, with some posts praising its anti-NIMBY stance and potential to “swipe away the gloom,” and others decrying it as “tech-bro nonsense on stilts”.

Critics, however, see greenwashing and hubris. Local MP Nick Timothy (Conservative, West Suffolk) slammed it as “completely unrealistic,” mocking the proposal’s misspelling of Haverhill and questioning the “forest” label amid farmland loss. Environmentalists, via groups like Smart Growth UK, warn it would raze grade 2 farmland, vital for food security in a nation producing just half its needs, and ecologists have calculated that construction emissions undermine any biodiversity gains.

The Guardian’s follow-up queried its “green” credentials, noting East Anglia’s water scarcity and risks to Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Reddit threads have dismissed its AI-generated visuals as investor bait, predicting “poorly-built, lifeless” sprawl from Labour donor developers. MetaFilter users have lampooned it as NRx (neoreactionary) fantasy, mixing blockchain dreams with human-rights suspensions. Local community leaders fear village erasure, with calls to “preserve” local heritage.

As of late November 2025, no formal plans are submitted, and Phase 1’s pledge drive feels rather like a litmus test for viability amid these divides.

Echoes of Ambition: Similar Schemes and Their Fates

This isn’t the first grand urban reset in modern Britain, and history offers sobering precedents. The 1946 New Towns Act gave birth to successes like Milton Keynes, now a 250,000-person town with a “Forest City” grid of parks and radials, completed in the 1960s after visionary planning by Llewelyn Davies.

Contemporaries like Stevenage and Harlow faced backlash for brutalist aesthetics and social isolation, with residents decrying “concrete jungles” that prioritised speed over soul (see Future House’s slogan above.) Post-1970s, schemes faltered: Ebbsfleet Garden City, touted in 2014 for 15,000 homes, has delivered under 10% by 2025, plagued by funding shortfalls and market volatility. Regeneration bids, like England’s Levelling Up projects, see completion rates below 20%, victims of bureaucratic silos and economic shocks.

Globally, the “Forest City” moniker evokes Malaysia’s $100 billion eco-utopia, launched in 2016 for 700,000 residents on reclaimed islands. Backed by Country Garden’s Belt & Road billions, it promised green luxury but devolved into an “eerie ghost town”, with just 9,000 inhabitants living amongst empty towers, due to foreign investor flight, environmental degradation (dying mangroves, fish stock collapse), and accessibility woes. Reddit users in r/malaysia attribute this to elite-driven design ignoring locals, which starkly mirrors UK fears of Forest City 1 becoming a speculator’s folly.

These tales reveal a pattern: bold visions may thrive on political will but, upon solidification, often crumble under overambition, poor execution, cost overruns, and community disconnections.

Cracks in the Foundations

For all its allure, the foundations of Forest City show cracks before they’ve even been laid.

Environmentally, the 45,000-acre footprint means a net green loss, with only 27% offset by new forest, exacerbated farmland erosion (the UK loses land for nearly 2 million meals yearly,) its construction’s carbon footprint, and water-stressed East Anglia risks chalk stream depletion, despite promises of reservoirs.

Economically, CLT scalability is unproven at this magnitude; £100 billion without subsidies invites private inequities, like premium zones eroding its affordability. Filling a million-person void assumes an endless spillover from Cambridge, ignoring remote work and demographic shifts toward smaller households.

Socially, it courts disruption; villages “integrated” will likely mean displacement, fuelling NIMBY revolts and undemocratic overreach via Development Corporation powers. Equity gaps loom, as merit-based allocation favors the privileged, while car dependency lingers without a proven tram network. Politically, Labour’s housing push clashes with green lobbies, who accuse them of breaking pledges and the “startup speed” timeline ignores HS2-style delays.

As critics note, it’s visionary but very vulnerable: “We need to build up existing cities, not greenfield fantasies”.

(John Sutton)

Solutions and Alternatives

Forest City 1 promises to deliver 400,000 homes by building an entirely new metropolis from scratch. The unspoken assumption is that this is the only way to achieve scale, affordability and infrastructure at speed. That assumption is wrong. Britain already has faster, cheaper, less destructive and politically easier paths to the same goals, paths that most European countries with better housing records have been quietly following for decades.

Here are the proven alternatives that would together deliver millions of homes, regenerate declining towns, restore nature and cost the taxpayer a fraction of a new mega-city:

Urban Regeneration & Greyfield Redevelopment

Britain is full of half-empty high streets, derelict retail parks, abandoned office blocks and decaying industrial estates, collectively known as “greyfield” sites. These already have roads, sewers, schools and GP surgeries nearby.

- Scale potential: The Letwin Review identified land for 500,000 homes on large greyfield sites alone. Campaign group Create Streets has mapped capacity for over 14,000 homes just on surface car parks around railway stations in Greater London.

- Recent successes:

- King’s Cross (London): 67 acres of former railway land, leading to 50,000 jobs and 4,000 homes.

- Salford Quays (Manchester): derelict docks now house 55,000 residents, MediaCity has also been a success.

- Wolverhampton’s Canalside South: former steelworks, now 1,000 homes and a new metro extension, all without touching green fields.

- Cost advantage: Land values are lower than greenfield, contamination remediation is now largely grant-funded, and infrastructure upgrades are incremental rather than the £20 to 30 billion needed for a new city.

Gentle Densification of Existing Towns and Cities

British suburbs are some of the lowest-density in Europe (Parisian suburbs are 2 to 3 times denser yet still leafy and desirable). Small-scale infill can add huge numbers of homes while improving walkability.

- Street votes (currently being piloted under the Levelling Up Act): residents on a street can vote to allow mansion blocks or mews houses in place of bungalows, with strict design codes. Early modelling by Policy Exchange suggests 500,000 to 700,000 additional homes nationwide.

- Railway corridor intensification: building 4 to 8-storey flats above and beside stations, (personal experience of staying in such flats on Station Approach in Epsom tells me that this works well.) Transport for New Homes calculated that just 25 major rail corridors could yield 1 million homes within 1 km of a station.

- Examples abroad we could copy tomorrow:

- Tokyo: here private railways routinely build mid-rise housing around stations, constructing upwards of 250,000 homes a year with almost no public subsidy.

- Montreal: “plex” triplexes and sixplexes with mandatory greenery keep the city affordable and beautiful.

- Freiburg (Germany):The Vauban district retrofitted a military base into 5,000 car-light homes with trams and co-ops.

Targeted New Settlements, but Smaller and on Brownfield-First Sites

If we genuinely need new communities, we can build them at scales of 10,000 to 50,000 people (the size that historically works best) on ex-airfields, former power stations or Ministry of Defence land.

- Northstowe (Cambridgeshire): 10,000 homes on a former RAF base, already under construction, using existing roads.

- Ebbsfleet (Kent): struggling because it was greenfield; contrast with Bordon (Hampshire), a 2,400-home eco-town on MoD brownfield that is thriving.

- The Netherlands’ Almere: 60,000 homes built since 1976 on polder land, but crucially linked from day one to Amsterdam by high-speed rail.

Real Community Land Trusts & Public–Private Land Pooling (at manageable scale)

Instead of betting everything on one gigantic CLT, replicate the proven models:

- Champlain Housing Trust (Vermont): 3,200 permanently affordable homes across one city; scalable and successful.

- London CLT and St Clement’s Hospital scheme: 250 homes on former NHS land, delivered in 2024 with zero public subsidy beyond the land value write-down.

- Milton Keynes Development Corporation’s original model (which Forest City claims to admire) actually worked because it captured land-value uplift incrementally and reinvested it, something that can be done on dozens of smaller sites without creating a new corporation.

Policy Levers that cost Almost Nothing yet Unlock Millions of Homes

- Immediate permitted development rights for 3 to 4 storeys above existing shops (as trialled in 2020 but watered down).

- Ending the “hope value” lottery in compulsory purchase, the single biggest reason brownfield sites stay empty.

- Taxing vacant land and empty homes at punitive rates (Liverpool’s empty-dwelling premium brought 5,000 homes back into use).

- Reforming leasehold and introducing common-hold, making flats attractive to families again.

(map by Burrough Green Parish Council)

The Numbers Add Up, Without a Single New City

Here are some calculations for alternative solutions to the housing crisis:

- Brownfield: Developing Brown / greyfield sites would provide homes for 1.2 to 1.8 million with almost zero loss of farmland.

- Gentle Densification: This could add 800,000 to 1.2 million homes with zero loss of farmland.

- Station-adjacent intensification: 700,000 to 1 million with a loss of under 5000 acres.

- 20 medium-sized new settlements (at 20 to 50k each) 600,000 to 800,000, loss under 30,000 acres (mostly brownfield)

- Total: 3.3 to 4.8 million with a loss of under 45,000 acres of farmland / countryside

In short, Britain can build more homes than Forest City 1 promises, at lower financial and ecological cost, with less political risk, and without gambling everything on one unproven mega-project led by a handful of private individuals.

The real barrier has never been lack of land. It has been political cowardice, vested interests and a strange national addiction to grand, headline-grabbing gestures instead of the patient, distributed, boringly effective reforms that actually work.

Forest City 1 is the latest and most extravagant example of that addiction. The alternatives above are not utopian, they are already working in Dutch suburbs, Swiss cantons, Japanese railway towns and pockets of England itself. All they require is the will to copy success instead of chasing spectacle.

(Robert Edwards)

Sources & References

Below is a list of the main sources and references used:

Core Forest City 1 Documents & Media

1. Official Forest City 1 website

2. Forest City 1 launch event at The O2 (Nov 2025)

3. Detailed proposal PDF (public version)

Media Coverage & Commentary

4. The Guardian: How ambitious ‘forest city’ plan for England could become a reality

5. The Telegraph: The ‘bonkers’ plan to build a brand new city for one million people

6. Cambridge Independent: ‘Forest City’ proposed east of Cambridge for one million people

7. Create Streets / Sam Bowman thread on X welcoming the idea but questioning scale

8. Smart Growth UK critique; “Forest City: the wrong answer in the wrong place”

Historical & International Comparisons

9. Centre of Cities “Everything you need to know about new towns”

10. House of Commons Library: New Towns Act 1946 and subsequent programmes

11. Create Streets “The Case for Brownfield First”

12. Policy Exchange: “Street Votes: A New Route to 700,000 Homes”

13. Transport for new homes: “Rail Corridors Report”

14. Letwin Review (2018) final report on build-out rates & land-banking

15. BBC News: Forest City: Inside Malaysia’s Chinese-built ‘ghost city’

Data & Statistics

16. CPRE: “State of Brownfield 2025” (1.6 million homes possible on registered brownfield)

17. ONS / DLUHC: English Housing Survey & land-use data (farmland loss)

18. National Food Strategy (Dimbleby 2021) & subsequent farmland-loss modelling

19. Create Streets / YIMBY Alliance: London car-park mapping (1 million homes)

Academic & Think-Tank Sources

20. Intergenerational Foundation reports (co-founded by Shiv Malik)

21. London Society: “Garden Cities vs Garden Villages: lessons from Letchworth to Ebbsfleet”

22. University of Sheffield: “Carbon costs of large-scale housebuilding”

Community & Social Media Reactions

23. Reddit inc: r/HousingUK Forest City megathread (Nov to Dec 2025)

24. Metafilter: Forest City thread

(Hugh Venables)

Beleaguered Cities

Penned by Cambridge-based scholar and writer F. L. Lucas in 1929

Build your houses, build your houses, build your towns,

Fell the woodland, to a gutter turn the brook,

Pave the meadows, pave the meadows, pave the downs,

Plant your bricks and mortar where the grasses shook,

The wind-swept grasses shook.

Build, build your Babels black against the sky,

But mark yon small green blade, your stones between,

The single spy

Of that uncounted host you have outcast;

For with their tiny pennons waving green

They shall storm your streets at last.

Build your houses, build your houses, build your slums,

Drive your drains where once the rabbits used to lurk,

Let there be no song there save the wind that hums

Through the idle wires while dumb men tramp to work,

Tramp to their idle work.

Silent the siege; none notes it; yet one day

Men from your walls shall watch the woods once more

Close round their prey.

Build, build the ramparts of your giant town;

Yet they shall crumble to the dust before

The battering thistle-down.

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Dec 2025)

*Update (Feb 2026)

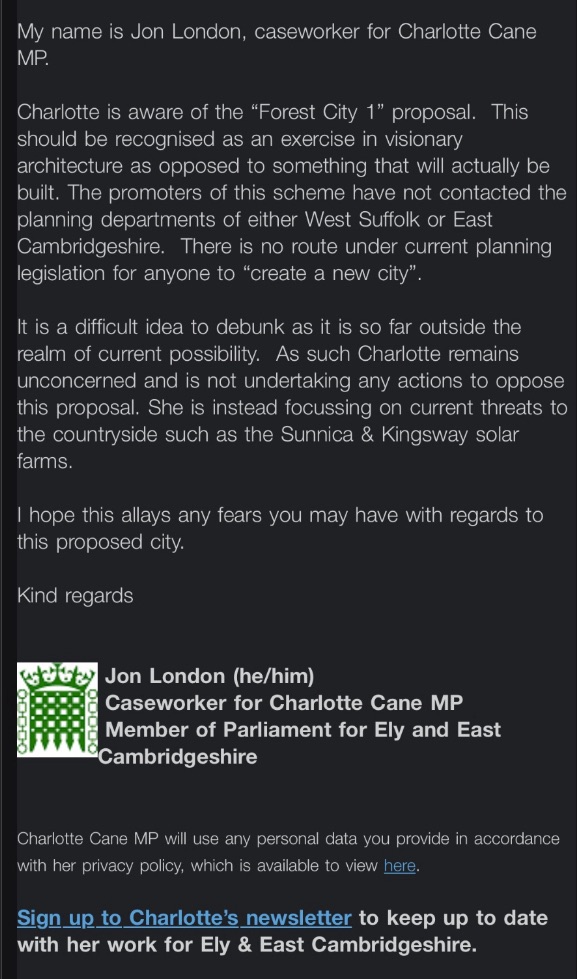

It looks like this ridiculous project may not be going ahead after all:

easier and cheaper on green fields than using brown field sites so more money for the developers Homes need to be near stations and or bus routes which are not available in this region.They will have to fight over the bit of land that could be covered in solar panels!!Can it be proved that this many people will want homes to be able to work in Cambridge The destruction of the already stressed areas for wildlife should be protected at all costs Already Cambridge is swamped with cramped housing developments with very little concern for wildlife and habitat protection .It’s the wrong development in the wrong place

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good points, for these and other reasons I doubt it will ever go ahead, but the idea of it and the precedents it sets are destructive enough on their own, which is why it must be opposed

LikeLike

thanks for writing this sound and well researched article

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank-you, I’m glad you found it interesting or useful

LikeLike