What Causes Them, Where to See Them, and a Glossary of Terminology

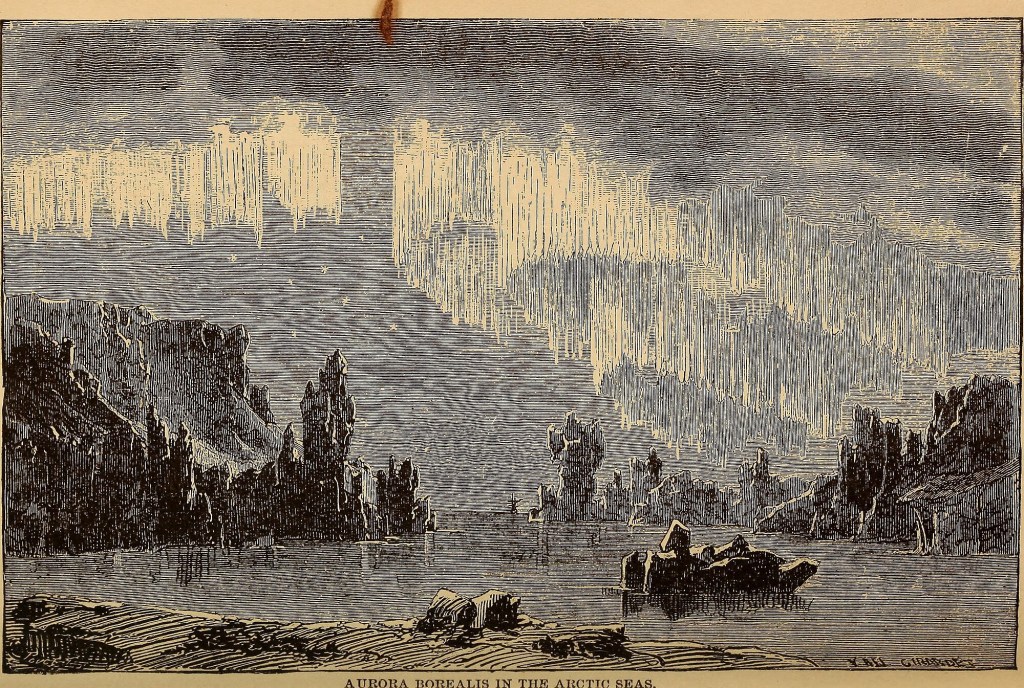

The Aurora Borealis, commonly known as the Northern Lights, must rank amongst one of nature’s most breathtaking spectacles. These shimmering curtains of light, dancing across our night skies, casting ethereal ribbons of green, purple and red, have inspired awe, myths, and scientific curiosity for centuries.

In recent years, particularly through 2025 and into 2026, auroral displays have been exceptionally vivid and widespread. We’re in the declining phase after the Sun’s solar maximum (it peaked around 2024 to 2025), but strong geomagnetic storms continue to push auroras further south, sometimes as far as mid-latitudes in Europe, the US and beyond.

Too-ticky in Moominland Midwinter by Tove Jansson

What Causes the Aurora Borealis?

The spectacle of the aurora borealis results from fierce interactions between the Sun and Earth’s atmosphere. The Sun constantly emits a stream of highly charged particles called the solar wind and during periods of heightened solar activity, such as solar flares or coronal mass ejections (CMEs), this wind intensifies, hurling billions of tons of plasma toward Earth.

Earth’s magnetosphere (its magnetic field) deflects most of these particles, but some become trapped and funneled along magnetic field lines toward the polar regions. There, in the upper atmosphere (roughly 60 to 250 miles up), the particles collide with oxygen and nitrogen atoms and molecules.

These collisions ‘excite’ the atoms, boosting their electrons to higher energy levels and when the electrons drop back to their ground state, they release this energy as photons, or visible light. The process resembles how a neon sign glows, but on a planetary scale.

Why the Colours Vary

The colour of the northern lights depends on the gas involved and the altitude of the collision:

Green is the most common colour, produced when energised oxygen emits light at altitudes around 60 to 150 miles.

Red is rarer, from oxygen at higher altitudes (over 150 miles), where collisions are less frequent but release more energy. Intense red often tops strong displays.

Purple, blue, or pink displays are caused by nitrogen, typically at lower altitudes (below 60 miles). These appear during powerful storms.

Yellow or white are simply mixtures of green and red, or overlapping emissions.

The lights often form dynamic shapes: curtains, arcs, rays, coronas, or pulsing patches that can shift rapidly.

(Magic Carpet Media)

Best Places and Times to See Them

Your chances of seeing the northern lights depend heavily on how strong the geomagnetic activity is. You typically want a Kp index of over 5 for reliable sightings in Scotland, and over 6 to 7 farther south). As of writing (20th January) we are in a high-activity phase of the solar cycle, so displays have been frequent and widespread, even reaching southern England.

Aurora season lasts from September to March and peaks around the equinoxes in September / October and March. The best time to view them is usually 10 pm to 2 am, with clear, moonless skies and minimal light pollution essential. Always check real-time forecasts via AuroraWatchUK (based here at Lancaster University in Lancashire), Met Office Space Weather, or use apps for alerts.

Here are some of the best places to see them in Northwest England (weather permitting of course)

Lake District This national park has few built-up areas so low levels of light pollution, it is also mountainous so offers lots of high elevation spots (the higher the better).

Derwentwater near Keswick, reflections over the lake really enhance displays.

Wasdale / Wastwater, remote, extremely dark with a dramatic mountain backdrop.

Langdale Valley or Ennerdale Water, both secluded valleys with excellent dark skies.

Grizedale Forest, forested but with clearings and high points offering good northern vistas. Low light pollution makes it reliable for horizon sightings.

Beacon Fell Country Park (near Preston This designated Dark Sky Discovery Site is levated, rural, and dark, good for lower Kp events (5 to 6) showing faint glow or pillars.

High ground near the Pennines (e.g., Yorkshire Dales edges in northwest, like around Ingleborough or Ribblehead) the open moorland gives panoramic northern views, Ribblehead viaduct becomes particularly popular when the lights are forecast.

Tan Hill Inn, the highest pub in England, on the Yorkshire / Cumbria border, is a good for aurora spotting with the added bonus of being a pub!

Arnside Knott or Silverdale on the Lancashire / Cumbria border offers coastal views with dark skies and is part of Arnside & Silverdale AONB, The northern horizon over Morecambe Bay can show activity despite the light pollution from nearby Heysham power station and port.

The Forest of Bowland is easier to get to for most Lancashire residents, the high fells and Hodder valley are dark as long as you have the hills between you and the urban conurbations of Burnley, Blackburn, Clitheroe and Preston to the south and west.

Tips for UK Aurora Hunting

- Avoid light pollution Head to rural areas or designated Dark Sky Parks.

- Weather matters Clear skies are crucial; check Met Office forecasts alongside aurora alerts.

- Apps & Alerts Use AuroraWatch UK for text/email notifications when activity rises.

- Patience Even in top spots, it’s not guaranteed every night as it depends on the mood of the sun.

Glossary of Key Terms

- Aurora Borealis The northern lights; a natural light display in Earth’s upper atmosphere near the North Pole, caused by solar particles exciting atmospheric gases.

- Aurora Australis The southern lights; the equivalent phenomenon near the South Pole.

- Solar Wind A continuous stream of charged particles (mostly electrons and protons) emitted from the Sun’s corona.

- Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) A massive burst of solar wind and magnetic fields released into space, often triggering strong auroras when Earth-directed.

- Geomagnetic Storm A temporary disturbance of Earth’s magnetosphere caused by enhanced solar wind; rated G1 (minor) to G5 (extreme), with higher levels producing brighter, more widespread auroras.

- Magnetosphere The region around Earth dominated by its magnetic field, which deflects most solar wind particles.

- Excitation The process where atoms or molecules gain energy from collisions, moving electrons to higher energy states before releasing light upon returning to ground state.

- Auroral Oval A ring-shaped zone around each magnetic pole where auroras most frequently occur.

- Kp Index A scale (0 to 9) measuring global geomagnetic activity; higher values indicate stronger storms and better aurora chances at lower latitudes.

- Solar Cycle An approximately 11-year period of varying solar activity, from solar minimum (quiet) to solar maximum (peak flares and CMEs); the current cycle has driven exceptional auroras through 2025 / 2026.

Illustration from The frozen zone and its explorers; a comprehensive record of voyages, travels, discoveries, adventures and whale-fishing in the Arctic regions for one thousand years (1874)

Oh, it was wild and weird and wan, and ever in camp o’ nights

We would watch and watch the silver dance of the mystic Northern Lights.

And soft they danced from the Polar sky and swept in primrose haze;

And swift they pranced with their silver feet, and pierced with a blinding blaze.

They danced a cotillion in the sky; they were rose and silver shod;

It was not good for the eyes of man — ’twas a sight for the eyes of God.

It made us mad and strange and sad, and the gold whereof we dreamed

Was all forgot, and our only thought was of the lights that gleamed.

From The Ballad of the Northern Lights, by Lancashire-born poet Robert W Service (1874-1958)

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Jan 2026)