Biology, Ecology and Management of the Common Bulrush, Typha latifolia

Typha comes from the Ancient Greek name for the plant túphē (τύφη), and latifolia from the Latin words latus (‘broad’) and folium, (‘leaf’)

The common bulrush, Typha latifolia, also more correctly known as ‘Greater Reedmace’, occasionally by it’s American name ‘Cats-tail’, and commonly as ‘bullrush’ with two ‘ls’ is a perennial herbaceous plant belonging to the Typhaceae family.

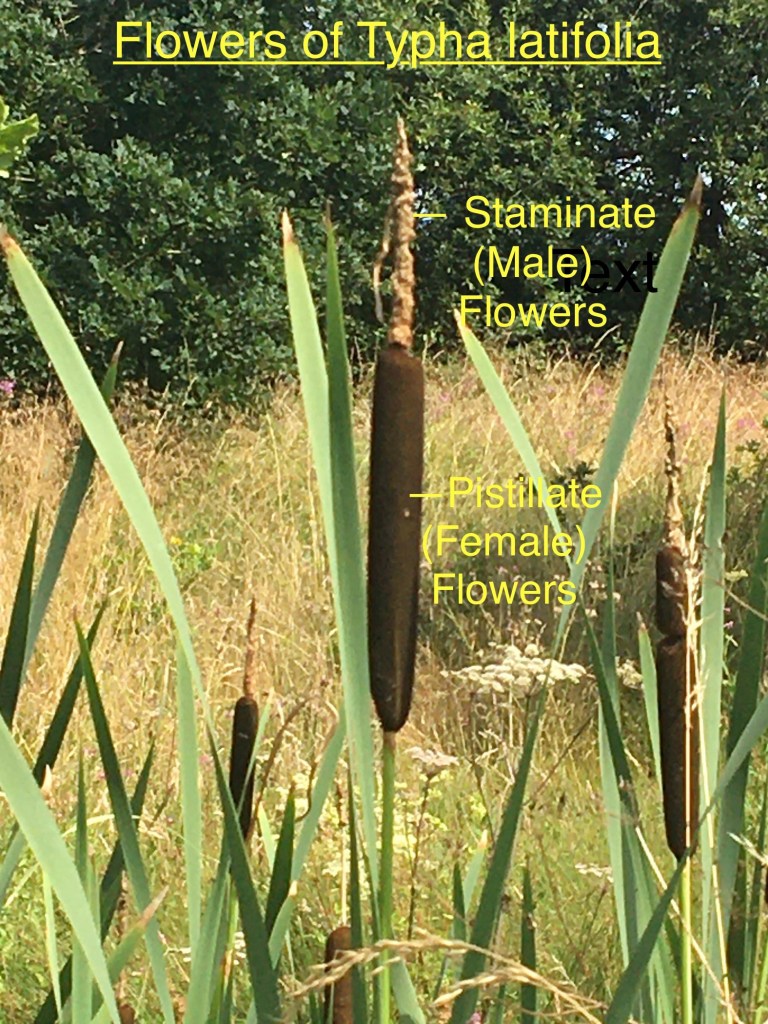

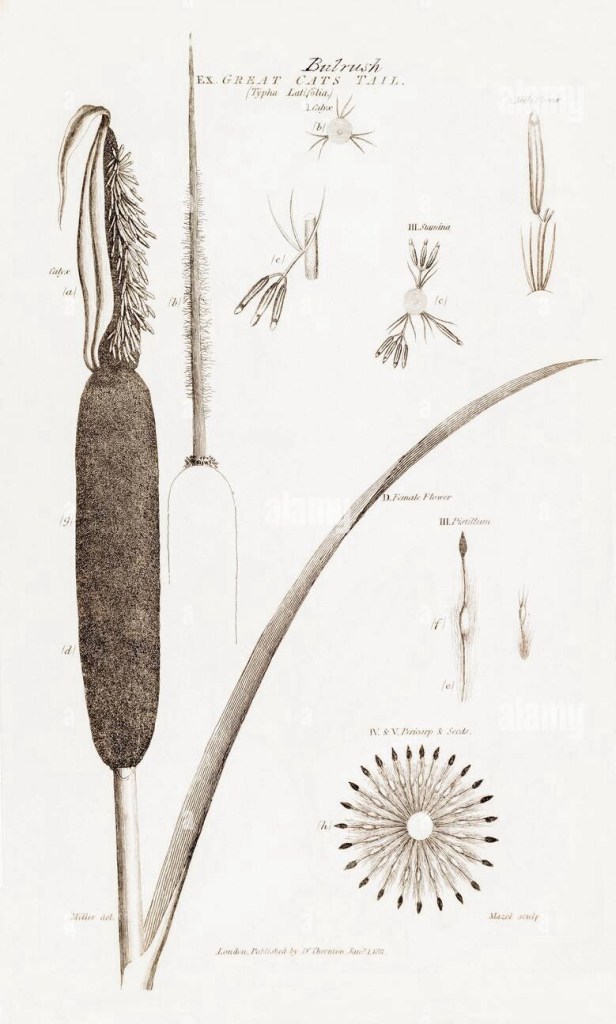

It can grow to impressive heights of up to 3 metres, with long, flat, sword-like leaves that are grey-green in colour and can reach 3cm in width. It’s most distinctive feature, however, is the inflorescence: a dense, cylindrical spike divided into two parts.

The upper section bears the male flowers, which are yellowish and produce pollen, while the lower, thicker part consists of the female flowers, which mature into the familiar brown, velvety ‘poker’, ‘cigar’ or ‘Cat’s tail’ that persists through winter.

(Tanya Jennings)

Robust Rhizomes

Bulrush spread via robust rhizomes underground, forming dense colonies that can dominate wetland edges, and flowering occurs from June to August, with wind-pollination ensuring widespread dispersal. Come autumn, the female spikes burst open, releasing fluffy seeds on the breeze, each equipped with a downy parachute for travel.

You’ll find bulrushes thriving in a variety of wetland habitats but they prefer still or slow-moving freshwater, tolerating depths up to 1 metre, and are adaptable to nutrient-rich waters, though they avoid highly acidic conditions unlike their bog-dwelling cousins Common Rush (Juncus effusus) and Bog Rush (Schoenus nigricans).

Ecosystem Engineers

Bulrushes are true ecosystem engineers, their dense stands create vital habitat for wildlife, birds like the reed warbler and Bittern nest among the stems, while Dragonflies and Damselflies use them as perches. The leaves and rhizomes provide food for creatures like Water Voles, and the fluffy seeds are gathered by birds for nesting material.

In terms of water quality, bulrushes act as natural filters, absorbing excess nutrients and pollutants through their roots, helping to prevent algal blooms in our rivers and lakes. They also stabilise banks, reducing erosion, and their decomposition contributes to peat formation in transitional wetlands, in many ecosystems they take the successional baton from the Sphagnum I wrote about in my previous article.

Our wetlands owe much of their biodiversity to these plants. They support invertebrates, amphibians like the great crested newt, and even rare fish species.

Bulrush damaged by Cosmet moth larvae (Limnaecia phragmitella) feeding in the seed-heads over winter

(Ben Sale)

Historical and Practical Uses

Humans have long valued the bulrush. In ancient times, the fluffy down was used for stuffing pillows and mattresses, while the leaves were woven into mats, baskets, and even thatch for roofs. The young shoots and rhizomes are edible, foragers might boil them like asparagus or grind the roots into flour during lean times.

In our industrial history, bulrushes played a role in water management around canals and mill ponds, today, they’re used in constructed wetlands for sewage treatment, harnessing their natural filtering abilities, and conservationists plant them in restoration projects to revive degraded marshes.

However, they’re not entirely without fault; in some areas, dense growth can choke waterways, requiring management.

Management of Bulrush

In nutrient-enriched or hydrologically altered wetlands, bulrush can form near-monocultures. This reduces the area of open water, shades out rarer plants (such as lesser reedmace Typha angustifolia) and limits habitat variety for wading birds and amphibians.

Drainage history, eutrophication from surrounding farmland (excess nutrients from slurry-spraying, fertilisers etc), and stable low water levels often favour dense stands.

The most common conservation tool is seasonal cutting or mowing. Annual or biennial cutting in late summer or autumn, after seed set but before winter die-back, weakens rhizomes over time and prevents excessive litter buildup. In some wetland reserves, stems are often cut above water level or, for stronger control, below the surface in winter when plants are dormant. Biomass removal is key, as leaving cut material creates thick mulch that suppresses other species.

In paludiculture trials (wetland farming on re-wetted peat), such as Lancashire Wildlife Trust’s bulrush wetter farming project, periodic harvesting serves dual purposes: controlling density while providing sustainable biomass for insulation, bioenergy, or even emerging building materials.

Water level manipulation is another powerful, non-chemical method. Raising water levels (through sluice control or bunding) can drown out dense stands, while controlled draw-downs followed by cutting exposes rhizomes to frost. At some sites fluctuating levels mimic natural flood cycles, preventing dominance and encouraging mixed vegetation.

Targeted Control in Sensitive Sites

For stubborn monocultures in high-value sites, mechanical methods like crushing (using tracked vehicles to flatten stands) or creating channels through dense beds can open up habitat corridors. These approaches allow fish, amphibians, and invertebrates to move more freely and promote native plant recolonisation.

Chemical options are rarely used in British conservation efforts due to impacts on non-target species and water quality regulations. When applied (under strict permits), aquatic-approved herbicides target late-summer growth when plants translocate energy to roots.

Grazing by hardy breeds like Konik ponies or Highland cattle has been trialled in fen and marsh restoration. Light grazing reduces litter and creates gaps, though bullrushes are resilient and not a preferred food.

Closing Thought

Watching bulrushes sway in the wind at a restored mere, or being woven to make furniture as my neighbour used to do with chairs when I was growing up, are timeless sights, and remind us that in the acts of managing and harvesting natures bounty we must strive to be stewards, not conquerors.

These plants and the wetlands they create have sustained us for millennia, and with thoughtful intervention, they can continue to do so, supporting wildlife, cleaning water, and perhaps even helping us build a more sustainable future.

In rushy fens, where waters creep,

The reed-bird builds her nest so deep;

Amid the bullrush flags so high,

That wave beneath the summer sky.

(Excerpt from ‘The Reed-Bird’ by John Clare)

British Flora (1812)

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for reading,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Feb 2026)