Biology and Ecology of Trichoceridae, commonly known as Winter Gnats or Winter Craneflies

Winter Gnats (Trichoceridae), also commonly known as winter craneflies, are a small family of delicate, long-legged flies in the order Diptera. They are particularly noticeable during the cooler months, and thrive in our damp, temperate climate where mild winter days provide perfect conditions for their activity.

Appearance and Identification

These insects look like miniature versions of the larger true Craneflies (Tipulidae), with slender bodies, extremely long thin legs, and clear wings that often extend past the abdomen tip.

Adults are typically 6 to 10mm in body length (excluding legs), with banded abdomens in some species and a main distinguishing feature is the presence of three simple eyes, called ocelli, on the top of the head, which true craneflies lack. Their wings show a distinct venation pattern visible under close inspection or magnification.

They are also frequently mistaken for mosquitoes or midges, but they do not bite humans and are completely harmless.

(BJ. Schoenmakers)

Common Species

Britain hosts around 10 to 14 species of Trichoceridae (taxonomy seems to be under review in some of the sources I used), belonging mainly to the genus Trichocera, and Northwest England provides ideal habitat due to its cooler temperatures, high humidity and abundant woodlands and wetlands.

Common species recorded here include:

- Trichocera annulata Often cited as one of the most widespread in Britain, though records become sparser the further north you go.

- Trichocera regelationis Suspected by some experts (e.g; from Natural England) to be among the commonest overall, especially as it is less strikingly marked and thus under-recorded.

- Trichocera hiemalis Active throughout winter and frequently encountered in our coolest regions.

- Others like Trichocera major, Trichocera saltator, and additional Trichocera. appear in records from the northwest, often in wooded or damp sites.

These flies favour moist, shaded environments: broadleaf woodlands, leaf litter accumulations, mossy banks, compost heaps, old mine workings (common in the Pennines and Yorkshire Dales), caves, hollow trees, and even gardens with decaying vegetation.

Our wet winters and frequent mild thaws (often 5 to 10°C) also allow them to remain active far longer than in drier southern counties.

(Don Loarie)

Life Cycle and Winter Activity

Northwest England’s climate suits their unusual life strategy perfectly: many species overwinter as adults in sheltered spots, emerging during late autumn, through winter mild spells, and into early spring. Adults are most active on calm, sunny days above freezing, often bobbing in characteristic ‘dancing’ swarms a metre or two off the ground. Males form these swarms to attract females; mating occurs quickly, after which females lay eggs in damp organic debris.

Larvae (maggots) are detritivores, feeding on decaying leaves, fungi, manure, or plant matter in moist soil or litter, this helps recycle nutrients in woodlands and moorland ecosystems and the adults provide vital winter protein for insectivorous birds like Treecreepers, Wrens and spiders when other insects are scarce.

The full cycle fits in with cooler seasons, with peak adult sightings from October to March, sometimes even on light snow cover during brief warm-ups, this cold tolerance comes from physiological adaptations, allowing enzyme function and muscle activity near freezing.

(James K. Lindsey)

Supercool Superflies

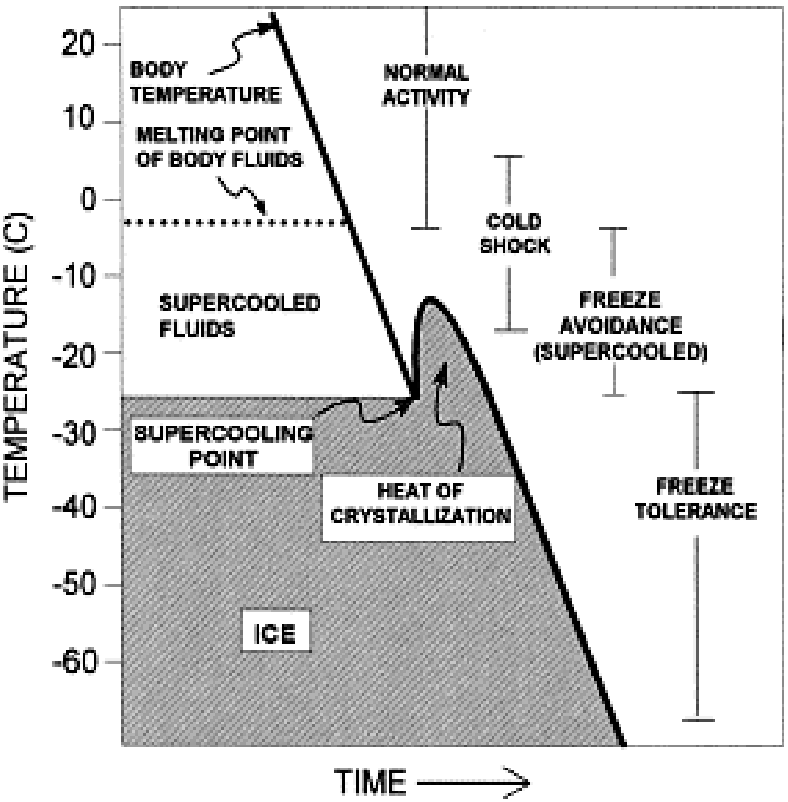

A Winter Cranefly’s primary tool in avoiding being frozen is supercooling: the ability to lower the freezing point of their body fluids without forming ice crystals.

These insects can supercool their bodies well below 0°C, enduring sub-zero temperatures for short periods without tissue damage, this is common among many winter-active invertebrates and helps them survive night-time lows or brief cold snaps. They are generally freeze-avoidant (susceptible to freezing if ice forms internally) rather than freeze-tolerant, so supercooling prevents lethal ice crystal formation in cells.

(Angela Ploomi et al)

Related cryoprotectants (cold-protective compounds) in their haemolymph (blood equivalent) such as sugars, alcohols like glycerol, or specific proteins, lower the supercooling point and stabilise tissues. These act like a natural antifreeze, inhibiting ice nucleation and preventing dehydration or cellular rupture. Survival after nights as low as -8°C has been recorded in these remarkable insects and it’s all thanks to these cryoprotectants.

Their physiology also includes cold-adapted proteins and enzymes that remain functional and efficient near or below freezing. Muscle contraction (essential for walking, swarming, or weak flight) works effectively in the cold, unlike in warm-adapted insects where muscles stiffen or enter a ‘chill coma’ (temporary paralysis).

This allows the characteristic and mesmerising ‘dancing’ swarms on mild winter days when other flies are inactive.

A Swarm of Gnats

Many thousand glittering motes

crowd forward greedily together

in trembling circles.

Extravagantly carousing away

for a whole hour rapidly vanishing,

they rave, delirious, a shrill whir,

shivering with joy against death.

While kingdoms, sunk into ruin,

whose thrones, heavy with gold, instantly scattered into night and legend, without leaving a trace,

have never known so fierce a dancing.

By the German-Swiss poet and novelist Hermann Hesse (1877 to 1962)

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for reading,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Feb 2026)