Nestled in the flood-plain of the River Ribble near Preston, Brockholes Nature Reserve is a testament to nature’s ability to recover from seemingly irreversible destruction, especially when given a helping hand by committed conservationists.

Once an expansive sand and gravel quarry, supplying material for construction projects like the nearby M6 motorway, this area has been transformed into a haven for a wide variety of wildlife species, and amongst its most secretive inhabitants are the Bitterns.

(Bill Boaden)

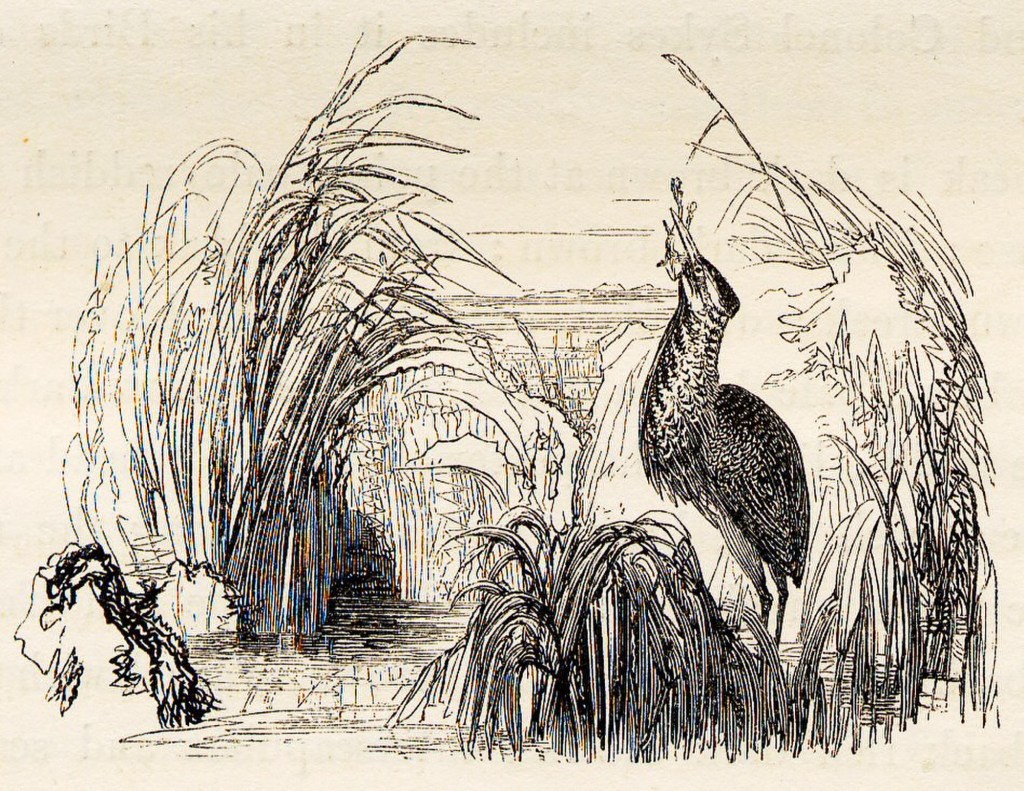

Hiding Heron

The Bittern Botaurus stellaris is a shy, elusive heron known for its exceptional camouflage, which allows it to blend seamlessly into the reedbeds where it resides.

The second half of its scientific name stellaris simply means ‘stars’ and reflects its nocturnal nature as it prefers to venture out at night, though for a long time the fact that it appears sluggish and sleepy when disturbed during daylight was thought to mean that it was merely idle.

Indeed it was known by the Ancient Greek philosopher and natural historian Aristotle as ‘oknos,’ a name suggesting “an idle disposition,” very likely because observers saw it hiding in swamps during the day, appearing lazy or reluctant to fly, however they were simply unaware that the bittern is nocturnal, active for feeding and mating mainly at night.

It seems that it has good reason to be nocturnal as it was once widely hunted for the table, it was even regarded as a gourmet delicacy because its meat does not have the typical fishy flavor found in most herons. During the medieval era it was rarely found in the kitchens of the peasantry though being protected in England and much of europe for the noble sport of falconry.

Baritone Booming

The first half of the Bittern’s scientific name, Botaurus, is a combination of the Latin words bos ‘oxen’ and taurus ‘bull’.

It came to have this unusual name by way of the Ancient Roman philosopher and natural historian Pliny the Elder, who described its call as sounding like an ox bellowing, which led to it being named ‘Taurus.’ Medieval scholars then recorded this as ‘botaurus,’ from which we get the modern day ‘bittern.’

Other names by which the Bittern has been known over the centuries are myriad and often fantastical, they include ‘miredromble,’ ‘botley bump’ and ‘bog-bull’. All of these derive from both its bog-dwelling tendencies and its unique and remarkable call.

Often likened to the sound of someone blowing across the top of a milk bottle, or the mournful moan of a distant foghorn, the call, the ‘boom’ of a Bittern has evolved to carry for miles and is used by males to attract mates and establish territory.

At Brockholes it is most audible at dusk around Meadow Lake or Number 1 Pit Lake, during their mating season which lasts from March to May, but it may be heard as early as January and as late as July.

(Lancashire Wildlife Trust)

Melancholic Marshes

For a long time the means by which the Bittern produced its characteristic sound were deeply mysterious, many thought it made by the bird inserting its long beak into reeds or mud. Indeed the English author and poet Chaucer wrote that a ‘a bitore bombleth in the myre’ by lowering its head ‘unto the water doun,’ but modern science has found that the bird produces this sound using a specialised lung membrane.

The mystery behind the melancholic call and remote places the Bittern inhabits led to it being featured in literature, fables, folklore and even books of faith including the Bible, where Isaiah, in prophesying Babylon’s destruction (Isaiah 14:23, KJV), mentions making it a “possession for the bittern,” symbolising desolation and loneliness.

In more recent times the marshes and reed-beds of the British isles must have seemed very desolate and lonely for its absence as for a long period it was extinct here, having been persecuted beyond tolerance.

Much of this persecution occurred during the 1800’s, when collectors shot many bird species to or beyond their ability to recover and after 1868, except for one young bird that was recorded in 1886 in the extensive reedbeds of Norfolk that remain a stronghold for the bird today, it became extinct as a breeding species.

In 1911 a nest was found by a miss E.L Turner and a Mr James Vincent who managed to rear them in captivity, they bred the birds over consecutive years until 1918 and 19I9 when a number of broods were safely released back into the Norfolk reeds.

They found that collectors, not drainage, were responsible for its scarcity and that if protected the birds flourished.

(Charles J Sharp)

Bittern Behaviour

By the late 1990s, the Bittern was once again critically endangered in Britain, with only 11 booming males recorded across the entire country. This time the decline was primarily thought to be down to loss of habitat, as their reed-bed homes were drained to create arable farmland.

This decline in numbers probably went unnoticed for so long as the birds themselves are so hard to detect.

As mentioned earlier the Bittern hides in reeds or other vegetation during daylight hours, and unless disturbed is not seen on the wing until their young require attention.

When approached it assumes a peculiar stance, pointing the bill upward so as to expose to view the thin buff neck with its irregular brown streaks, which, in reeds, confuse the eye enough to make it virtually invisible.

In this pose it will stand stock still and will not move a millimetre unless approached very closely, this is unwise to do though as it will strike out very suddenly with its sharp bill if threatened, aiming for the eyes.

When feeding young the female is less cautious, flying to-and-fro all day between the nest and the feeding ground. On the wing the bird looks a light-brown, almost cinnamon colour in sunlight and, unlike its relative the Heron, is compact with a short neck.

The flight is direct, slow and owl-like, with the wings moving faster than the measured and laboured beats of the Heron. Some individuals will fly fairly high, calling with a deep agh, agh, but others will hardly clear the reed tops and are more difficult to spot.

On alighting it will stand for a few moments, bill up and neck stretched as it turns its head about in all directions checking its surroundings, before sinking out of sight, and if disturbed will run fast with shoulders high and the head lowered, until suddenly slipping with ease out of sight.

If they are disturbed near their nest they will, like most ground-nesting birds, lead the threat away from the nest until satisfied that it is safe, although a Bittern’s nest is as hard to find as the bird itself, being a mere patch of flattened vegetation only a foot or so across and only just above the water.

(Roger Culos)

Breeding and feeding

Bittern lay their pale olive eggs in clutches of 4 to 6 from the end of March until June, with the young hatching around 25 days later. The young may leave the nest within a fortnight but are likely to hang around in the vicinity being fed by the female until they fledge, around 7 to 8 weeks later.

During this time it is only the female who feeds them, by regurgitating food directly into their beaks, the male doesn’t abandon his families though, although polygamous, mating with up to 5 females in a season, he still maintains his territory, booming to mark its bounds and chasing off any threats.

Prey is predominantly Eels, followed by frogs and other amphibians, other fish species, freshwater crustaceans like Crayfish and even small mammals like voles.

They catch these by utilising the tried and tested hunting techniques that all of their kind, the Herons and Egrets too, have used for millennia; by standing absolutely still, watching their hunting ground with sharp eyes, and striking at any movement with lightning-sharp speed, swallowing their prey whole immediately afterwards.

(Chme82)

Increased Bittern numbers

At Brockholes the team have increased Bittern numbers by creating not just breeding habitat for them but also habitats for their prey, refining techniques that were first developed at the neighbouring reserve of Leighton Moss, where Brockhole’s Bitterns likely came from.

These techniques include digging out parts of the reedbed to encourage new growth, managing water levels, and controlling deer populations to prevent overgrazing. These efforts paid off most notably in 2018, when bitterns bred at Leighton Moss for the first time in over a decade, and even more triumphantly last year, in 2024, when 10 booming males were recorded, marking a significant milestone in British Bittern conservation.

(Martyn B)

Bittern have even spread to Lunt Meadows at Sefton near Liverpool where, in 2021, they bred for the first time in centuries.

For those keen on spotting Bittern, the best times to visit Brockholes are during winter, when the birds might be seen venturing out onto the ice. The reserve offers various trails and hides, with the Look Out hide being one of the most popular vantage points for birdwatchers.

Patience is key, as Bittern are not easily seen, but it is well worth spending some time there as, part from Bittern, the reserve is home to a great variety of other wildlife, including waders, Brown Hare, Roe deer and occasionally Otters.

For more information or to plan your visit, check out www.brockholes.org or www.lancswt.org.uk, it’s well worth visiting as, while Bittern themselves might be hard to spot, the experience of searching for them amidst the natural beauty of Brockholes is a reward in itself.

Where the gaunt bittern stalks among the reeds

And flaps his wings, and stretches back his neck

And hoots to see the moon; across the meads

Limps the poor frightened hare, a little speck;

And a stray seamew with its fretful cry

Flits like a sudden drift of snow against the dull grey sky

Excerpt from Humanitad, by Oscar Wilde

A B-H

Feb 2025

One thought on “The Elusive Bitterns of Brockholes”