Lancashire Looms

The Lancashire loom is a semi-automatic power loom that works by propelling devices called ‘shuttles’ to-and-fro to weave together warp (longitudinal) and weft (lateral) threads.

It was invented by James Bullough and William Kenworthy in 1842 as an improvement on the original power loom first patented by Edmund Cartwright in 1784.

If that first loom was responsible for starting the industrial revolution, the Lancashire loom helped Britain dominate it, but, as we’ll find out later in this series it also, rather paradoxically, led to its decline.

Lancashire’s Largest Mills

As the Lancashire loom allowed weavers to work on several looms at once, rather than just the one, it allowed the weaving industry to scale up from cottage to factory scale, and at its peak the scale of the industry was vast, with many mills having hundreds of looms clattering away in their cavernous weaving sheds.

Here are some of the largest surviving mills in Lancashire:

India Mill, Darwen

Housing over 1000 looms India Mill was one of the largest weaving mills in Lancashire. At its peak, it likely housed over 1,000 looms, which was typical for major weaving sheds in the region. Built in 1867, it sat empty and didn’t start operating until machinery was finally installed in 1871.

Renowned for its iconic 303-foot Italianate chimney and its vast weaving shed the mill produced Cotton for export until closing in 1991 and being repurposed as a business center.

(David Dixon)

Trencherfield Mill, Wigan

Built in 1907, Trencherfield was one of the last great spinning mills, equipped with 240,000 spindles at its peak. While it focused on spinning rather than weaving, its output fed weaving mills across the whole country. Its massive steam engine, with a whopping 28ft flywheel, is still operational as a museum piece and underscores its industrial scale.

(Galatas)

Moor Lane Mill, Lancaster

Originally a spinning and weaving complex Moor Lane Mill grew into a large weaving operation before transitioning to other uses (now student accommodation). It is thought to have held 400 to 600 looms during its cotton heyday.

(Stephen Richards)

Helmshore Mills (Higher Mill and Whitaker Mill), Rossendale

Higher Mill (built in 1796) and Whitaker Mill (built in the 1820s) are now combined to form Helmshore Mills Textile Museum but were once two different enterprises. Whitaker Mill was a cotton mill, with a loom count of 200 to 300 which put it on the smaller side of things, whereas Higher Mill was a wool-fulling mill.

(Chris Allen)

Queen Street Mill, Burnley

Opened in 1895, Queen Street Mill (which I’m using as the model mill for this series) is the last surviving steam-powered weaving mill in the world. While its current count of 308 Lancashire looms might seem modest compared to other industrial giants, this number is less than a third of what there used to be.

Historically, it was part of a cooperative; The Queen St Manufacturing Co. Ltd and ran 1040 looms at its peak in 1940, all bought from the Burnley companies Pemberton & Co. and Harling & Todd Ltd.

Sadly, over the decades, many of these looms were sold off or cannibalised bit-by-bit to keep the rest of the looms running, as their manufacturers had closed, so by March 1982 only 440 Lancashire looms remained and it became financially unviable to keep it open.

(To read more about the history of Queen Street Mill please see my article Raising Steam)

(author)

Lancashire’s Industrial Peak

By 1860, Lancashire had over 2,650 cotton mills with 350,000 power looms collectively.

The largest weaving sheds in the north and west of the county (e.g., Burnley, Blackburn and Darwen) often operated 1,000 to 2,000 looms each, especially under the ‘room and power’ system where multiple firms shared space.

Spinning mills in the southeast (e.g., Oldham and Bolton) focused on spindles (millions in total) rather than looms, supplying yarn to these weaving giants and later to the rest of the world when they caught onto the value of the cotton industry.

This was all down to the semi-automatic Lancashire Loom, which allowed one weaver to manage 4 to 8 looms, massively boosting efficiency and leading to hundreds of workers being in regular and consistent employment.

Water to Steam

A typical water wheel in the 18th or 19th century might generate up to 10 to 50 horsepower, and a single mechanized loom from that era required about 0.5 to 2 horsepower, so (roughly) one water wheel could power anywhere from 5 to 100 looms, with 20 to 30 being a practical average for a medium-sized wheel.

With the first power looms requiring all the concentration of their operator this originally meant that a mill would only employ 10 to 30 weavers.

For quite a while, from the invention of the power loom in the late 1700’s to the early 1900’s, this system worked well and the industry thrived, being a vast improvement (as far as industrialists were concerned, not so much the luddites!) on the old cottage industry that had existed previously for centuries.

But as they say “time and tide waits for no man” and the water wheels were soon swept away by the invention of steam engines that could produce hundreds of horsepower (Queen Street’s engine ‘Peace’ could generate 600hp) thus powering hundreds of looms.

(author)

Mechanical Power Transmission

Having the capability to run hundreds of looms was a great boon to mill owners but brought with it many technical challenges, the main one being how to transmit all that horsepower to all the looms and other machines in the weaving shed.

In a modern-day factory electrical control panels containing components like circuit breakers, transformers and relays, manage the electricity flow to all of the equipment centrally and transmit it through cables, but in our 19th and 20th century cotton mills this power has to be transmitted mechanically.

This initially proved a challenge but engineers met it very ingeniously, in Lancashire the main mechanism used was the rope drive, whereas lines of rope running from grooved pulleys on the engine powered shafts on each floor, these were in use at Trencherfield Mill and Ellen Road Mill at Rochdale, but engineers at other mills had different ideas.

In Queen Street, where all of the looms are on the ground floor, this problem was solved using hundreds of feet of line shafts and leather belts connected like so;

First the power from the engine was passed into horizontal shafts, then, through toothed gearing, this was transferred up to vertical shafts.

Next these connected to longer 16ft horizontal shafts which, connected to each other with bearings, ran the whole 200ft length of the weaving shed.

Power from the shafts, which hang from the ceiling, was conveyed down to each loom through a leather belt.

This could be quickly uncoupled from the drive shaft of the loom by pulling a simple lever which pulled the belt to a free-running wheel, thus allowing the operator to turn off their loom without disrupting the rest of the floor.

The Workings of a Lancashire Loom

A Lancashire loom works by interlacing two sets of threads: the warp (longitudinal) and the weft (transverse). Here’s a breakdown of how it works:

Key Components

- Warp Beam: This is a large roller at the back of the loom that holds the warp threads under tension.

- Heddle Frames (or Harnesses): Sets of wires or cords with eyes in the middle through which warp threads pass. These frames lift or lower specific warp threads to create a shed (a gap for the weft to pass through).

- Shuttle: A small device that carries the weft thread back and forth across the warp through the shed.

- Reed: A comb-like structure that pushes (or “beats”) the weft thread into place after each pass of the shuttle.

- Cloth Beam: A roller at the front where the finished woven fabric is wound.

How it operates

- Warp Setup: The warp threads are wound onto the warp beam and threaded through the heddles and the reed. These threads are kept under tension throughout the process.

- Shed Formation: The heddle frames move up or down (controlled by a mechanism like a dobby or tappet system) to separate the warp threads into two layers, forming a shed. The specific pattern of movement determines the weave structure (e.g; plain weave or twill).

- Weft Insertion: The shuttle, loaded with a bobbin of weft thread, is propelled through the shed from one side of the loom to the other. In a Lancashire loom pthis was typically done mechanically using a picking stick or overpick/underpick motion powered by the loom’s crank.

- Beating Up: After the shuttle passes through, the reed moves forward to push the newly inserted weft thread tightly against the already woven fabric.

- Take-Up: The finished fabric is gradually wound onto the cloth beam, and the warp beam releases more thread as needed.

Still Weaving

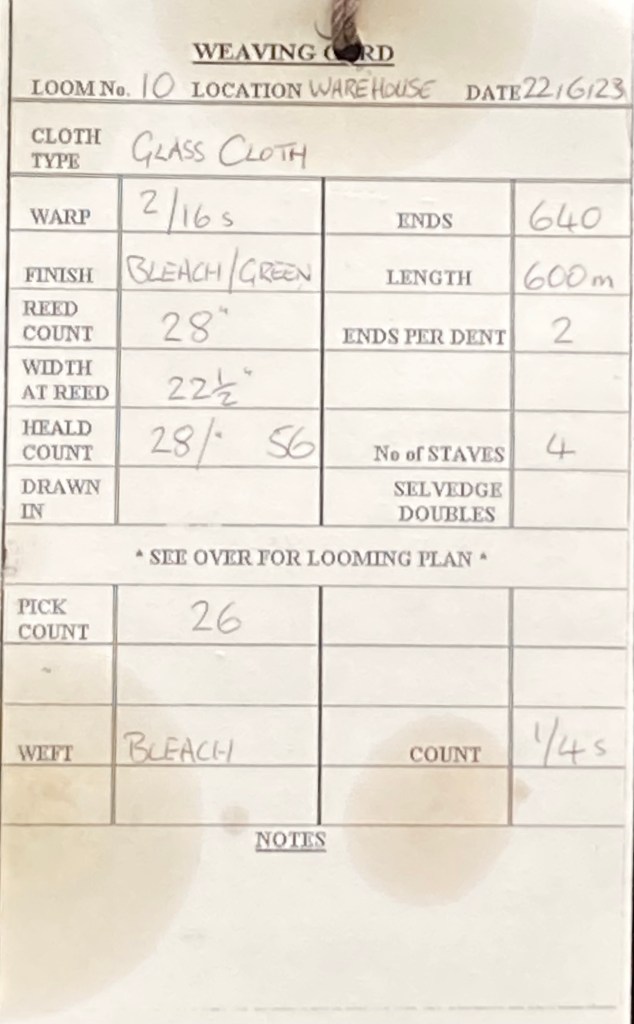

Queen Street’s looms still produce textiles which you can buy in their souvenir shop, including tea-towels, calico and glass clothes, they are occasionally commissioned to weave one-off items and limited runs too, such as blue and white shirting sold exclusively to Old Town of Holt in Norfolk.

I’ll look at the lives of the weavers who operated the looms, the towns that were built to house them, and the decline of Lancashire’s cotton industry in the next part of this series, but for now let’s enjoy this Victorian poem by an anonymous author;

A Lesson from the Loom

A while I watched my busy shuttle fly

Across the loom between the op’ning sheads;

And then I thought, e’en thus at my employ,

I may a useful lesson learn. Like threads

Our lives are woven in the web of time;

Our moments are the picks which pass between the sheads.

And if we make the woof sublime,

The piece, perchance, may please when it is seen

By the Great Master’s ever-watchful eye;

And of His praise we each may get a share,

And His dear approbation yield in joy

A rich reward for all our toil and care.

And we may find that when life’s piece is made

We all shall be by Him far more than paid!

A B-H

(March 2025)

5 thoughts on “Cotton Chronicles; Lancashire Looms”