Introduction

Our street is much like any other in Great Britain, it’s in the middle of a largish housing estate, built in the 70’s and situated between boxy brick council houses built in the 50’s and a grey, rabbit-warren like concrete council estate built in the 80’s, known locally as ‘Lego-land’.

Along our street sits a mix of semi-detached houses and bungalows, all with their own front and back gardens.

When I moved here a few years ago it was the first time I’d lived on a suburban housing estate like this, previous homes had included town and city-centre apartments, terraced houses and rural cottages, and the flats above a 16th century country Inn, all built long before the concept of housing estates had even been conceived.

So it was a new environment and I began to see all the things which made it different to the other places I’d called home.

The first thing I noticed when moving in was that we had one of the few remaining front gardens left, most of the others, on a street numbering up to 160, had been paved over to park cars on.

Over the years we noticed more and more of these front gardens disappear under concrete and tarmac, and came to realise that many back ‘gardens’ were in fact now yards too, either paved with flags, concrete or that most vile and abhorrent of modern inventions; plastic grass.

This appalled me, these homes were designed with gardens for the sake of their occupant’s mental and physical health. They were intended to be green spaces of grass, shrubs, flower-beds and trees, for the enjoyment of both man and beast, for the betterment of the both the local and wider environment.

So how could it be that they were disappearing like this? smothered and destroyed and lost, and at a time when much of our countryside is being unnecessarily buried under yet more houses?

How could people be so ignorant of the loss to wildlife, the environment and future generations?

For if this is happening on such a scale in our neighbourhood then it must be happening everywhere else too, on all the other identical suburbs across the width and breadth of the country.

And if magnified so then the loss must be vast, almost on a par with that of the loss of hedgerows during the Post-War Agricultural Intensification of the 50’s.

So, I thought, what can be done, clearly something has to be, we’re losing too much. But how? How can one lone voice bring attention to this issue? Will it change people’s minds? Can I make a difference?

Therefore, with that in mind I decided that my next article should be this, the one you are reading now, because although I’m under no illusion that I may make any difference, I cannot remain silent and mute and passively watch this destruction continue.

Our Urban Gardens

Our urban gardens are more than just aesthetic havens or spaces for leisure, they can be vital ecological assets too, playing a significant role in supporting biodiversity, mitigating climate change, and enhancing environmental resilience.

In a country where urbanisation and agricultural intensification have reduced natural habitats, they can serve as critical green spaces that sustain wildlife, improve air quality, and contribute to the well-being of both ecosystems and communities.

Here we explore the multifaceted nature of these pockets of green land and look at the many reasons for keeping and improving them for nature and future generations.

Biodiversity Hotspots

The UK’s estimated 24 million private gardens cover roughly 10% of the country’s land area and form a vast network of miniature ecosystems that provide food, shelter, and breeding grounds for a wide array of species.

The number and variety of species they support is impressive, including pollinators like bees and butterflies, birds, small mammals like hedgehogs, and amphibians;

- Pollinators and Plants: Gardens with native plants, wildflowers, or nectar-rich species attract bees, butterflies, and other pollinators, which are essential for food production and ecosystem stability. For example, Bumblebees, which have declined due to habitat loss, thrive in gardens with plants like Lavender, Foxglove, and Comfrey. The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) notes that even small gardens can support over 2,000 species of insects, which are critical for pollination and as a food source for birds and bats.

- Birds and Mammals: Gardens provide nesting sites and food for birds such as Robins, Sparrows, and Tits. Features like bird feeders, hedgerows, and berry-producing shrubs sustain avian populations, especially during harsh winters. Similarly, Hedgehogs, a species in decline, rely on gardens for foraging and shelter, with compost heaps and log piles offering ideal habitats.

- Amphibians and Reptiles: Garden ponds, even small ones, provide aquatic lifelines for frogs, Toads, and Newts, which face threats from wetland loss. These water features also support dragonflies and other aquatic insects, enhancing local biodiversity.

By planting diverse native species and incorporating wildlife-friendly features like ponds, hedges, and insect hotels, gardeners can significantly boost local ecosystems, creating refuges for those species under pressure from habitat fragmentation.

Climate Change Mitigation

As green spaces our gardens play a crucial role in mitigating climate change too, by acting as carbon sinks, reducing urban heat, and managing water runoff.

In the British isles, where extreme weather events are becoming more frequent (see the drought we had earlier this year for example,) gardens help buffer environmental impacts;

- Carbon Sequestration: Trees, shrubs, and soil in gardens absorb carbon dioxide, helping to offset emissions. Mature trees in larger gardens can sequester significant amounts of carbon, while even small lawns and flowerbeds contribute to carbon storage. Composting garden waste further reduces methane emissions from landfills, enhancing the carbon cycle.

- Urban Heat Island Effect: In cities and towns, especially our three largest; London, Birmingham, and Manchester, gardens counteract the urban heat island effect, where concrete and asphalt trap heat. Vegetation in gardens cools the air through shade and evapotranspiration. Studies suggest that urban green spaces, including gardens, can lower local temperatures by up to 5°C, improving livability during heatwaves.

- Water Management: Gardens with permeable surfaces, such as lawns or gravel, reduce surface runoff and alleviate pressure on urban drainage systems. Rain gardens, designed to capture and filter rainwater, are increasingly popular, helping to prevent flooding and recharge groundwater.

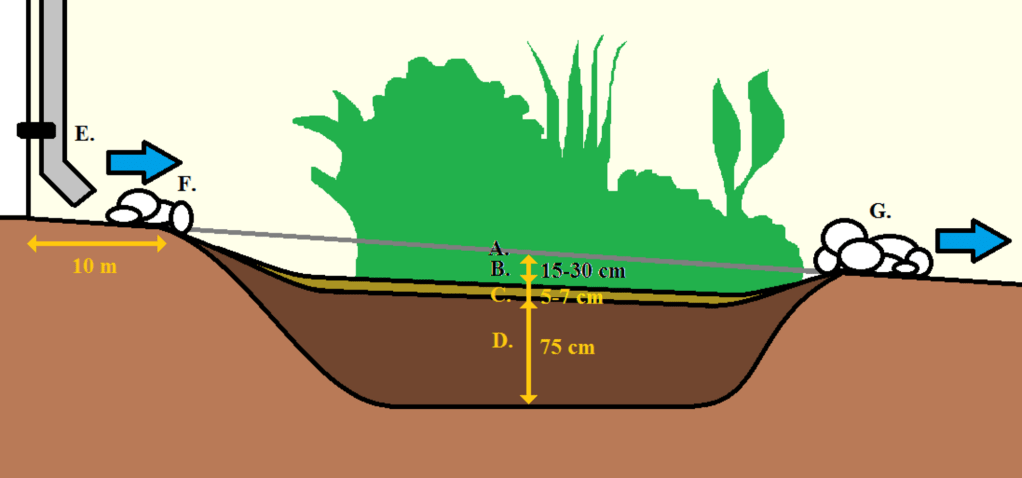

A. Ground level: the inflow (F.) must be higher than overflow (G.), stone bed protects the soil in both places, the house (E.) should be 10 meters from the rain garden

B. Depth of rain garden: the depth of the rain garden soil is 15-30 cm under the ground level for stagnant water

C. Top filter layer: 5-7 cm wood chips or compost or mulch

D. Rain garden soil: 60% sand, 20% compost and 20% topsoil

Soil Health and Ecological Services

Healthy garden soils teem with microbial life, which supports nutrient cycling and plant growth. Practices like organic gardening, mulching, and avoiding chemical pesticides enhance soil fertility and structure.

These efforts contribute to what are called ‘ecological services’; pollination, pest control, and water filtration, which benefit both the garden and the wider area.

For example, encouraging natural predators like Ladybirds and Lacewings in gardens reduces the need for chemical pest control, thus creating a naturally balanced ecosystem.

Wildlife Corridors

Acting rather like stepping stones in an increasingly fragmented landscape, urban gardens form corridors for wildlife to move between habitats, they may link parks and nature reserves, preventing species from succumbing to genetic isolation (in-breeding in layman’s terms) which can lead to local extinction.

This connectivity is vital for species like hedgehogs, which require access to multiple gardens to forage effectively.

Initiatives like the RHS (Royal Horticultural Society) and Wildlife Trusts’ “Wild About Gardens” campaign encourage gardeners to create wildlife-friendly spaces, and charities like Froglife provide valuable information to those wishing to make their gardens part of this network.

Mental and Environmental Synergy

Beyond their ecological benefits, gardens support human well-being, which indirectly aids conservation efforts, a feedback system called ‘environmental synergy’. Simply put; people are more likely to look after neighbourhoods they are happy within.

Engaging with nature in gardens reduces stress and fosters a connection to the environment, which in turn encourages sustainable behaviours.

Community gardens, allotments, and school gardens further amplify this impact by promoting local food production, reducing food miles, and educating people about biodiversity.

Challenges

Despite their importance, our urban gardens face myriad challenges, here are two of the main ones;

Paving over front gardens for parking

This has become a trend in urban areas, and is one which particularly upsets and annoys me (hence this article.)

It reduces permeable surfaces, significantly impacts watercourses and increases flooding risks.

When gardens are replaced with impermeable materials like concrete or asphalt, rainwater cannot infiltrate the soil, leading to increased surface runoff. This excess water overwhelms drainage systems, especially during heavy rainfall, causing water to accumulate on streets and flow into nearby watercourses, such as rivers and streams.

The rapid influx can erode riverbanks, carry pollutants from urban surfaces into water bodies, and elevate water levels, heightening flood risks in low-lying areas.

The town our suburb is in, Padiham, has, like several other British towns in recent years, suffered from severe flooding, and there is no doubt that urbanisation and the paving over of urban gardens with hard-standing contributed towards it.

Despite this homeowners still persist in the practice, being either oblivious or ignorant to the potential future risks they are posing to their own town, businesses and community.

Studies, such as those conducted by the RHS and Herriot-Watt University, have indicated that urban areas with high paving rates experience up to 50% more runoff, exacerbating flooding and degrading watercourse ecosystems.

Yet our local councils and central government do nothing to prevent it, seeming to prefer the expenditure of millions of pounds of taxpayers money on flood defences instead of flood prevention. Although I understand that there is clearly little they can do about private land without huge and sweeping changes in legislation.

Use of Artificial Grass

The use of artificial grass in gardens can have several harmful effects on the environment and local ecosystems.

Unlike natural grass, artificial grass is typically made from non-biodegradable plastics, which do not absorb water, leading to increased surface runoff and a higher risk of localised flooding, especially during heavy rainfall.

This impermeable surface also prevents soil aeration and disrupts habitats for insects, worms, and other organisms, reducing biodiversity. Additionally, artificial grass can overheat in direct sunlight, creating microclimates that harm nearby plants and contribute to urban heat islands.

Over time, the plastic fibers break down into microplastics, polluting soil and nearby watercourses. According to environmental studies, artificial turf can also release toxic chemicals, such as PFAs (Per and polyfluoroalkyloids, also known as ‘forever chemicals’,) into the ground, posing long-term risks to wildlife and human health.

Change

To change things for the better, and stop this hugely damaging loss to nature and our environment, we can do several things;

- Reconsider our Car Ownership: Do we really need a car in the first place? Or two cars? Nowadays it is common for homes to have several cars, but do we need that extra car? After all most of us managed perfectly fine for decades with just the one family car per household. Can we use public transport instead, car-share, or cycle to work?

- Choose Permeable Paving: If you must park in front of your house do you really need hard-standing over every square foot? Such things as grass-bricks are available, (see images below) which allow vegetation to grow and water to infiltrate, they can be maintained very easily by mowing over them (and in my opinion look a lot better!)

- Remove your Paving: Removing impermeable surfaces and replacing with native plants, grass, or the afore-mentioned rain-gardens can create a vibrant front garden that attracts pollinators, cools the surrounding area, and enhances the appearance of both your house and street (called ‘curb appeal’). Start by breaking up the hard surface, removing the rubble, and enriching the soil for planting. Opting for low-maintenance, drought-resistant plants can keep upkeep simple while promoting biodiversity. Bear in mind that planning permission may be required for areas over 5 square metres (as it is to pave an area this size with impermeable materials in the first place).

The Future

Hopefully the selfish trend of paving over our urban green spaces will pass and we will rediscover the love of gardens that Britain has been famous for since Roman times, and we may come to realise how much we have lost.

We may also start to undo the damage we have already inflicted.

We can do this for the wildlife that we see in our gardens now, or for our neighbours, who might not like living in the middle of a vast carpark! But most importantly we can do it for the future, for the generations that will come after us, so that they do not stand to inherit a sterile, lifeless desert, but a healthy and green landscape instead, fit for everyone, and everything, to call home.

Garden-Lore

Every child who has gardening tools,

Should learn by heart these gardening rules:

He who owns a gardening spade,

Should be able to dig the depth of its blade.

He who owns a gardening rake,

Should know what to leave and what to take.

He who owns a gardening hoe,

Must be sure how he means his strokes to go.

But he who owns a gardening fork,

May make it do all the other tools’ work

Though to shift, or to pot, or annexe what you can,

A trowel’s the tool for child, woman, or man.

‘Twas the bird that sits in the medlar-tree,

Who sang these gardening saws to me.

Juliana Horatio Ewing (1841-1885)

If you enjoyed this article you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting my site,

Alex Burton-hargreaves

(June 2025)

Excellent. I would like to reblog it to give wider circulation

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank-you, that would be great, I wanted to tidy it up a little bit before I published it but, like a garden, sometimes things are better when they’re a little scruffy round the edges!

LikeLiked by 1 person