(Stephan Sprinz)

The vast tidal estuary of Morecambe Bay is one of the most significant sites for birdlife in the British Isles, supporting over 240,000 birds annually.

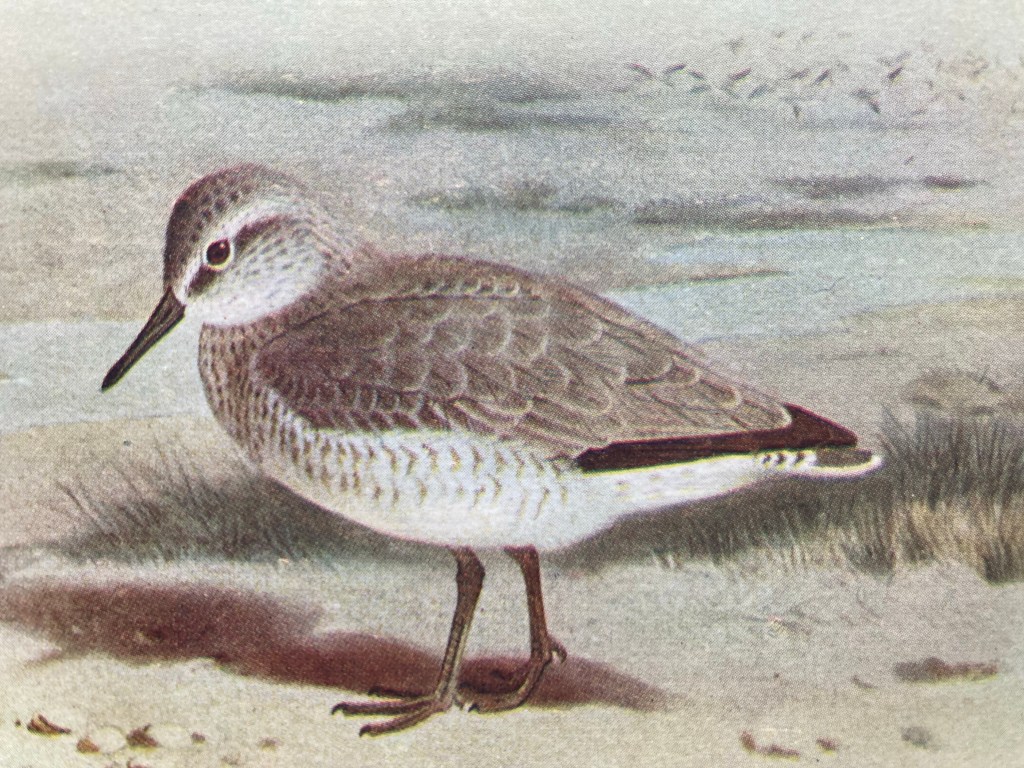

Among its most iconic avian visitors is the Knot, Calidris canutus, a small, stocky wading bird known for its remarkable migrations and mesmerising flock displays.

A holarctic species, breeding in the high Arctic tundra of regions like Canada, Greenland, and Siberia during the brief summer months, these diminutive waders undertake epic migrations of thousands of miles to coastal estuaries like Morecambe Bay for the winter.

They are recognisable by their dumpy, short-legged build, and undergo a striking transformation between seasons. In summer, their chest, belly, and face glow a vibrant brick-red, while in winter, their primary season in Morecambe Bay, they sport a grey upper body and white underparts, with a faint wing-stripe visible in flight.

When resting or feeding birds on the windward side will constantly rise, take 2 or 3 fluttering wing-beats, and drop into the shelter of the flock, living in such exposed places they cannot stay still for long

(Image by Stephan Sprinz)

Mysterious Binome

The origins of its rather charming scientific name are a bit mysterious, we do know that the prefix was bestowed by the Ancient Greek philosopher, scientist, student of Plato and tutor to Alexander the Great; Aristotle, who described them as skalidris, or kalidris (καλιδρις) in the third chapter of book VIII of his History of Animals, when discussing birds associated with aquatic environments;

“Of birds, some live by rivers, marshes, or the sea, as for instance the heron, the osprey, the coot, the grebe, the kingfisher, and the water-rail; the skalidris and certain kinds of gulls, such as the herring-gull, are also found about waters. Some of these are exclusively aquatic, while others frequent both land and water.”

The origin of the second half of its binome (the technical term for a species’ scientific name) has been lost in the depths of time, as canutus could come from the Latin form of the Old Norse name Cnut or Knut, which means ‘knot’.

On the other hand it may relate to the legendary story of King Cnut (Canute), who commanded the tide to recede, suggesting the bird’s habit of foraging along the tide-line and running to and fro the water with every ebb, looking for all the world like they are afraid of getting their feet wet.

Although the exact origin of its name has been much-debated it could simply be onomatopoeic, referring to the bird’s call.

(Arnstein Rønning)

Key Knots

Knots are a key component of the wintering wader population of Morecambe bay, with an estimated 14,000 individuals present, contributing to the bay’s status as one of the UK’s most important sites for these birds. Their numbers peak between December and March, when they can be seen at high tide roosts, often in massive flocks that create one of nature’s most spectacular displays.

The vast intertidal mudflats, fed by five major rivers; the Leven, Kent, Keer, Lune, and Wyre, provide an ideal feeding ground for waders. The bay’s 310 square kilometers of intertidal sands and mudflats are rich in food, with a single square meter of mudflat offering the caloric equivalent of thirteen chocolate bars for hungry birds.

Knots feed primarily on shellfish, such as mussels and cockles, and worms, probing the soft sediments with their specialised beaks. This abundance of food makes the bay a critical stopover for those migrating through from their Arctic breeding grounds to further destinations and a winter haven for those staying here through the colder months.

The bay’s dynamic tidal range, one of the largest in the British Isles, exposes vast feeding areas twice daily. As the tide recedes, Knots follow the waterline, foraging alongside other waders like Oystercatcher, Curlew, and Dunlin.

When the tide rises, they gather in large flocks at high tide roosts on saltmarshes, shingle beaches, or sea defense groynes, often mixing with other species to create breathtaking murmurations; swirling, synchronised displays that rival those of the Starling.

These flocks, dominated by Knots, wheel and turn wildly in the sky, flashing their pale underwings in a mesmerising spectacle best seen a couple of hours before and after high tide.

(Charles J Sharp)

Ecological and Cultural Significance

Morecambe Bay has been designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest and recognised internationally for its wildlife, the Knot’s presence here demonstrating the bay’s importance as a wintering site for waders, with nine species, including Knots, occurring at internationally and nationally significant levels (exceeding 1% of the British population).

The bay’s birdlife has long been culturally important too, and is celebrated through initiatives like the Morecambe TERN project (1999 to 2002), which integrated avian-themed art into the promenade’s coastal defenses.

Steel sculptures of Knots, alongside other species like Dunlin and Cormorant, adorn Morecambe’s seafront, reflecting the community’s pride in its avian residents and their role in shaping the area’s identity.

(Immanuel Giel)

(The Wub)

Challenges Facing Morecambe’s Waders

Despite their abundance, Morecambe Bay’s waders face significant threats. Human disturbance, particularly during the winter months, can disrupt feeding and roosting, forcing birds to expend critical energy reserves needed for survival and migration.

Leisure activities, such as those during peak summer holidays, can inadvertently disturb high tide roosts, a problem the Morecambe Bay Partnership addresses through projects like ‘700 Days to Transform the Bay’ and ‘Headlands to Headspace,’ which promote coexistence between wildlife and recreation.

Environmental changes also pose risks. Rising sea levels, potential barrages, and habitat alterations threaten the intertidal zones waders rely on. Additionally, the decline in Cockle and Mussel populations, both key food sources, due to regulated fishing and ecological shifts, impacts their survival.

For instance, a 2023 survey noted high numbers of undersized Cockles and low adult stocks, leading to fishery closures that indirectly affect the birds’ food supply (see Cockle article for more details about this)

Globally, Knot populations are vulnerable, with nearly 300,000 wintering in the UK from Arctic breeding grounds. Their dependence on specific estuarine habitats makes them sensitive to any changes in these ecosystems.

Conservation efforts by organisations like the RSPB and Cumbria Wildlife Trust, which manage reserves such as Leighton Moss, South Walney, and Humphrey Head, are crucial for protecting the birds. These reserves provide safe roosting and feeding sites, with bird hides offering excellent viewing opportunities for visitors.

(author)

Spotting Knots

For birdwatchers, Morecambe Bay offers numerous vantage points to observe Knots. The best time is between late August and late May, particularly on days with high tides exceeding 8.5 meters, when birds are pushed closer to shore.

. Key locations include:

• Hest Bank: A prime spot with views of waders like Knots, accessible from Shore Road (LA2 6HN).

• Morecambe Promenade: Ideal for year-round birdwatching, with Knots visible following the tide line.

• South Walney Nature Reserve: Offers bird hides for viewing Knots and other waders, alongside resident seals.

• Grange-over-Sands and Kent Estuary: Mudflats here attract thousands of roosting birds at high tide.

• Leighton Moss RSPB Reserve: Close to Silverdale, this wetland paradise is perfect for spotting Knots and other species.

Visitors are urged to respect wildlife by remembering the countryside code, sticking to footpaths, keeping dogs on leads, and avoiding close approaches to roosts, especially in winter when energy conservation is critical for birds.

Third Edition (1926)

The Place To Be

By George Bernard Hough

On the western coast of this sceptered isle

rest your feet and pause awhile.

View the heights of the lakeland hills,

far away from satanic mills.

As you sit, and sip your tea,

watch the sun set on the sea.

Its golden orb lights up the sky,

as seabirds make their plaintive cry.

They visit us from far and wide,

and when the sea is at low tide,

you’ll see them feeding on the shore,

as they have done since days of yore.

Just a stride from our busy town

fishing boats bob up and down.

Anglers with their rod and line

fish from the sea wall wet or fine.

Our promenades a busy place

where you will see a familiar face.

A famous star looks on the town,

a man who took away ones frown.

Who, with his partner Ernie Wise,

(the one who was the smaller size)

helped make our town a place of fame

by taking on himself its name.

Children think it quite a lark

to spend time in our famed park,

take them there, make it snappy

and like our park they will be happy!

We locals of this lovely spot

are a really friendly lot,

it’s nice to see you every year,

we’ll make you welcome, never fear.

In case you wonder where I mean

that these attractions can be seen,

the place to rest along the way

is our delightful Morecambe Bay.

Far away across the sea

along the coast of italy,

the bay of Naples we espy,

a bay one has to see, and die!

So stay at home in the UK

and come instead to Morecambe bay,

the lakes and hills forever give

a bay one has to see, and live.

If you enjoyed this article please consider showing your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Aug 2025)

One thought on “Northern Shores: The Knots of Morecambe Bay”