Nature’s Autumnal Messenger

The Herald moth, Scoliopteryx libatrix, is a common native species known for its striking appearance and unique life-cycle that spans seasons in a way few other moths do. Belonging to the family Erebidae, it is often one of the first to emerge in spring and one of the last to be seen in autumn, earning its common name as a “herald” of changing weather.

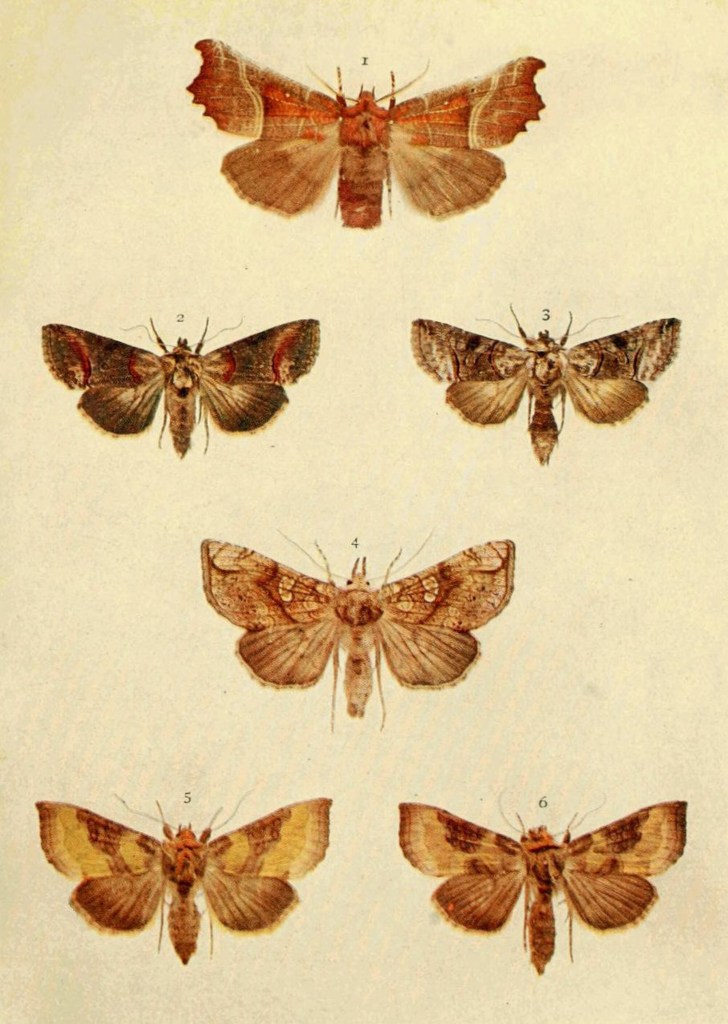

It is easily recognisable by its rich, reddish-brown forewings, which feature bold orange streaks and white spots, creating a flame-like pattern that stands out against its surroundings. The wings are scalloped along the edges, giving them a distinctive, wavy outline, and the moth holds them in a tent-like position when at rest. Adults typically have a wingspan of 40 to 45mm and the hindwings are paler, often grayish with subtle markings.

Caterpillars are slender and green or brown, their camouflage blending seamlessly with the leaves of their host plants.

(Hsuepfle)

Herald Habitat

Widely distributed across the British Isles, the Herald is generally common throughout England, Wales, Ireland, the Isle of Man, and the Channel Islands, though it tends to be more localised and less abundant in Scotland, it is very frequently caught by moth-trappers here in the Northwest.

It inhabits a wide variety of diverse environments including woodlands, parks, gardens, heathlands, and scrubby areas, primarily where its larval food plants like willows and poplars are present.

As one of the few moths that overwinters in its adult form, it often seeks sheltered hibernation sites including in outbuildings, barns, Limekilns, caves, under bridges, tunnels and the interiors of dry-stone walls, emerging in spring after feeding on nectar sources like ivy flowers in autumn.

Life Cycle and Behavior

The Herald has an extended flight period, typically from June to November, with some individuals active as early as March after hibernation. Adults overwinter in sheltered spots, emerging in spring to mate, females lay their eggs on host plants, and larvae hatch in late spring, feeding nocturnally on leaves while hiding during the day.

Caterpillars grow rapidly, pupating in a loose silk cocoon spun between leaves by mid-summer and new adults appear from late July, feeding on nectar and sap, they are attracted to lights and sugar, making them easy to catch by moth trapping.

(Ian Alexander)

The Meaning of Its Scientific Name

The scientific name Scoliopteryx libatrix was assigned by Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish biologist renowned as “the father of modern taxonomy,” in 1758, and its etymology reveals insights into the moth’s morphology and, to a degree, its behavior.

Its genus name Scoliopteryx derives from ancient Greek: ‘skolios’ (σκολιός), meaning “crooked,” “curved,” or “bent,” combined with ‘pteryx’ (πτέρυξ), meaning “wing.” This likely refers to the moth’s distinctively scalloped or wavy wing-edges, which give the forewings a curved appearance when at rest.

The species epithet libatrix comes from Latin ‘libo’ or ‘libat,’ meaning “to pour” or “to make a libation” (an offering poured out, often in religious rituals). Interpretations suggest it could mean “one who pours” or “sipper,” possibly alluding to the moth’s feeding habits of sipping nectar or sap.

Some sources, including A. Maitland Emmet’s The Scientific Names of the British Lepidoptera propose that Linnaeus might have drawn from classical imagery, though the exact reasoning remains speculative. Interestingly, the common name “Herald” may stem from this, evoking a messenger pouring out announcements, but it’s more likely tied to the moth’s seasonal appearances.

Threats to Hibernating Moths

Invertebrates choose their over-wintering sites carefully, picking locations that are sheltered, dry, draught-proof and free of predators. Even so they may occasionally select a site which is not quite so suitable, or simply suffer bad luck.

They often succumb to predation, either by small mammals like Wood mice, which have been documented preying on overwintering adults in sheltered locations like crevices or foliage, and Bats, which target active or emerging moths, though some species have evolved evasion tactics. Birds may snatch moths during daylight hours if they become exposed, or leisurely pick them off one-by-one all winter (the Wren in particular is good at this) and invertebrates like ground beetles and wolf spiders that hunt in overwintering habitats are a threat too.

Environmental factors pose significant risks as well, such as temperature fluctuations that can disrupt diapause or cause premature emergence, leading to starvation or exposure in unsuitable conditions, particularly for overwintering pupae.

Light pollution is another emerging threat, as it can interfere with seasonal cues, prompting moths to develop into adults too late in autumn and fail to overwinter successfully. Additionally, human-related disturbances like habitat loss from development, pesticide use, and even indoor heating in homes where moths seek shelter can awaken them prematurely, exposing them to harsh outdoor environments with limited food resources.

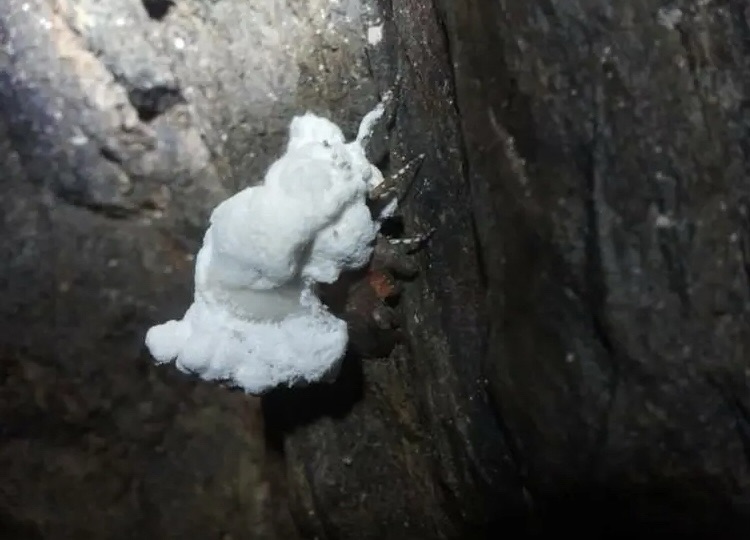

Finally (and perhaps most horribly) they may suffer the predations of infectious fungi.

Entomopathogenic Fungi

In some instances, if conditions are right (for the fungus that is, not the moth,) entomopathogenic fungi spores may settle on a hibernating moth and lead to its downfall. Entomopathogenic simply means “causing disease in insects” and the mechanisms by which a fungus achieves this are fascinating.

It begins with fungal spore penetration, by which the spores break into the body of the dormant moth through a multi-step process combining physical and biochemical processes. Initially, fungal spores (conidia) adhere to the insect’s hydrophobic epicuticle (the thin, outermost layer of the insect’s skin, evolved to repel water) through passive mechanisms like electrostatic force and adhesins (sticky compounds.)

Upon adhesion, the spores germinate in response to environmental cues such as moisture, temperature, and any lipids or nutrients secreted by the host insect, forming a ‘germ tube’ that develops into an ‘appressorium,’ a specialised swollen structure that exerts mechanical pressure to initiate penetration by the germinating spore.

This physical force is augmented by ‘enzymatic degradation’ as the fungus secretes a range of hydrolytic (water-based) enzymes, including lipases (breaks down fat) to get through the waxy epicuticle layer, proteases to degrade protein chains, and chitinases (chitin is the material that forms an insect’s skin.)

Once through the cuticle, the fungus enters the hemocoel (body cavity), where it proliferates as hyphae (branching filaments), evading the host’s immune responses while producing toxins like destruxins (acidic, anti-immunal compounds) or beauvericin to accelerate the death of the host.

Once the entomopathogen has taken over the moth’s body it will produce blastospores, essentially fruiting bodies, from the hyphae and spread via spores to any neighbouring insects.

In some cases this may lead to the whole colony of hibernating moths being wiped out in their sleep, leaving only their eerie-looking white corpses behind, sprouting strange growths and leaving the unwitting lay-person who stumbles across the scene feeling both revolted and horrified over what has befallen the hapless insects.

1: The Herald

2: The Dark Spectacle

3. The Spectacle

4: Golden Plusia

5, 6 Burnished Brass

To a Moth Seen in Winter, by Robert Frost

There’s first a gloveless hand warm from my pocket,

A perch and resting place ’twixt wood and wood,

Bright-black-eyed silvery creature, brushed with brown,

The wings not folded in repose, but spread.

(Who would you be, I wonder, by those marks

If I had moths to friend as I have flowers?)

And now pray tell what lured you with false hope

To make the venture of eternity

And seek the love of kind in winter time?

But stay and hear me out. I surely think

You make a labor of flight for one so airy,

Spending yourself too much in self-support.

Nor will you find love either nor love you.

And what I pity in you is something human,

The old incurable untimeliness,

Only begetter of all ills that are.

But go. You are right. My pity cannot help.

Go till you wet your pinions and are quenched.

You must be made more simply wise than I

To know the hand I stretch impulsively

Across the gulf of well nigh everything

May reach to you, but cannot touch your fate.

I cannot touch your life, much less can save,

Who am tasked to save my own a little while.

If you enjoyed this article please consider showing your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

I need to resist the urge to hibernate this winter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It would make sense wouldn’t it? Go to bed in November, wake up around the start of February, imagine the savings on heating bills!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating article, thankyou. I have up to 32 species of butterfly in my garden (designated wildlife Refuge garden )…haven’t done an inventory of the moths yet. I love your inclusion of prose and poetry in your writings. Julie Anne.

Envoye a partir de Outlook pour Androidhttps://aka.ms/AAb9ysg ________________________________

LikeLiked by 1 person