“Here we stand before your door,

As we stood the year before;

Give us whiskey, give us gin,

Open the door and let us in.”

It’s a bitingly cold December night in 19th century Rochdale, the streets are slick with frost, the air thick with coal smoke from countless chimneys, lanterns flicker outside the terraced rows, and suddenly, from the darkness, comes a low sound, a strange, wordless murmur echoing from the walls of the cobbled street.

Then they appear; a shadowy band of figures, faces blackened with soot and ashes, eyes gleaming through slits in crude masks made from card or old linen sacks, adorned by ragged clothes in riotously bright colours that flap about them like the tattered wings of a moth, scarlet ribbons, patched coats turned inside out, skirts on the men and breeches on the women.

Some sport bizarre animalistic heads, horns twisted from paper, or tall hats streaming with crimp paper.

They move as one, capering, mostly silent apart from their meaningless mumbles, seeking ale and warmth and a chance to turn the everyday world upside down.

These are the mummers, winter wanderers, slipping from door to door during the Twelve Days of Christmas and, lead by the Lord of Misrule, they approach your door.

Every year a new Lord of Misrule would be crowned to reign over the mayhem and merriment

“Any mummers ‘lowed in?”

A knock echoes. You peer out of the window cautiously. “Who’s there?” you tentatively call, but there’s no answer, just that eerie mumble.

You open the door just a crack, “any mummers ‘lowed in?” a masked form queries, relieved by the question, you answer “aye” and in they tumble, filling the warm kitchen with cold air and mischief.

For only when invited do the mummers break silence, bursting into song, a wild dance, or perhaps a quick, improvised skit full of mockery and nonsense, the men squeaking in falsetto, the women booming in mockery of the male voice, lampooning your neighbours gently, bringing the lord of the manor low in jest.

They might play loaded dice, tricking you into a foolish, but harmless bet, or simply whirl in a circle, stamping boots on the flagged floor. In return? all they ask for is a mince pie, a mug of ale, a few coppers dropped into a collection box, often for charity, a nod to the season’s goodwill amid the revelry.

This is no polished theatre, it was never intended to be, it is something more powerful; raw, ancient fun, rooted deep in the frozen midwinter soil and overseen by gods older than memory. Some say it echoes pagan rites of reversal, when the world was turned topsy-turvy to coax spring’s return. Others trace it to medieval feasts, where the Lord of Misrule reigned over chaos.

All we know is that in Lancashire’s hard-working mill-towns and villages, it was a brief escape from the often harsh realities of life, a chance to mock authority anonymously, to let loose before the wheel turns to a new year.

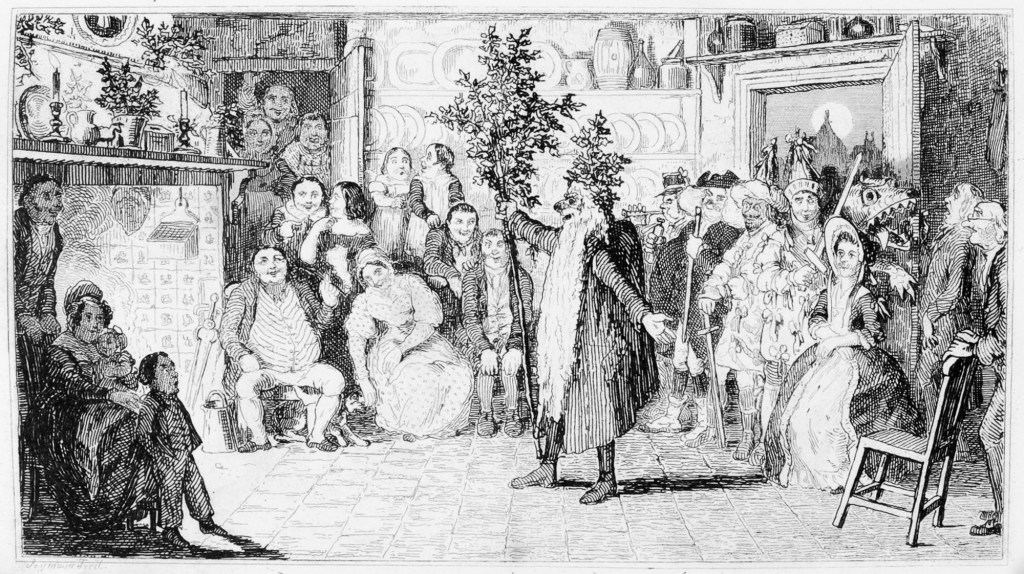

‘Mummers’ by Robert Seymour, 1836

Some theorise that the word mummer originated with Momus, the Ancient Greek god of mockery, or the Greek word mommo meaning ‘mask’.

It has also been associated with the Early German vermummen, meaning either ‘a disguised person’ or ‘to mask one’s face’.

“Roast beef, plum pudding, and strong beer!”

In some places, the performance grew more structured; a hero like bold St. George clashing swords with a Turkish knight or dragon, one falling “dead” only to leap up revived by a quack doctor’s comical cures. Beelzebub might rattle in with his stick and pan, demanding “roast beef, plum pudding, and strong beer!”

Yet in Lancashire, Christmas mumming stayed looser, being more about the disguise and door-to-door surprise than the full play, that grander drama was saved for Easter’s Pace-Eggers, those painted-egg beggars that you might see today in Bury or Hebden Bridge.

In these parts the Christmas mummers were of a more subdued nature, my father-in-law can remember the group that visited when he was a child, in the 50’s; they wore humble attire of apron, headscarf and blackface, and merely swept the floor or dusted the hearth, humming quietly to themselves the whole time, before being sent on their way with another penny in their pocket.

His account matches that of my nan’s from Poulton-le-fylde, who remembers hiding under the bed when they came to call, terrified.

Tightening Corsets

As the Victorian era tightened its moral corset, and the mills demanded sober workers, the wilder customs of mumming faded, and by the early 20th century, the soot-faced bands had grown rare, surviving here and there into the 1960s, before melting away like the feathery frost-ferns you might find on your window on a winter morning that disappear at the touch of the first ray of sun.

Yet on a crisp Christmas night, if you walk down an alley in the oldest part of town and listen carefully, you might still catch that faint murmur on the wind. a whispered memory of those masked revellers, turning darkness into defiant joy once more.

In comes I, old Father Christmas.

Welcome in or welcome not,

I hope old Father Christmas never will be forgot.

Though I’ve but a short while here to stay,

I am come to show you pleasure,

and to pass the time away.

I have been far, I have been near,

and now I come to bring you cheer.

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-hargreaves

(Dec 2025)

Fabulous……………………MUUUUUUUUUUUUM xx

LikeLiked by 1 person