Common Ivy, Ecology, Uses, and Historical / Cultural Context of

Common ivy, scientifically known as Hedera helix, is an evergreen climbing plant native to, and ubiquitous throughout the British Isles, excepting the far north and a few spots like the Isle of Man.

It is found in a variety of habitats, from woodlands and hedgerows to urban walls and old buildings where it can reach heights of 20 to 30 meters when supported by trees, cliffs, or structures, using its aerial rootlets to cling to surfaces.

While not overly picky it prefers moist, shady locations with moderately fertile soils, and tolerates a wide pH range, but it will avoid sites prone to extreme drought, salinity, or with highly acidic soils.

Its leaves vary by the plant’s growth stage; juvenile leaves are palmate, meaning that they have lobes with midribs that radiate from one point, while mature ones are unlobed and cordate, meaning heart-shaped, to make the most of the sunnier positions on the stem.

Ecologically Underrated

The roles Common Ivy plays in our ecology are vastly underrated; it provides year-round shelter for birds, Bats, small mammals, and insects, acting as a non-parasitic climber that does not harm host trees by drawing nutrients from them.

In late autumn, its greenish-yellow flowers offer vital nectar and pollen to over 70 species of insects, including Bumblebees, hoverflies, and wasps, when few other plants are blooming. The high-fat black berries, ripening in winter, are a crucial food source for at least 16 bird species, such as thrushes, blackbird, and woodpigeon, aiding seed dispersal.

Additionally, Ivy supports the larvae of butterflies and moths like the Holly blue, Comma, Early Thorn (pictured below) and Swallow-tailed moth, and in woodlands often forms dense groundcover in dry shaded areas, stabilising soil, preventing erosion and insulating the ground against the lowest of temperatures, protecting overwintering larvae hibernating beneath.

Historical Uses

Historically, Common Ivy has long been valued for its medicinal, symbolic, and practical applications. In ancient times, it was linked to pagan traditions; the Romans associated it with Bacchus, the god of wine, using wreaths to prevent intoxication, a custom that influenced early English folklore.

During the winter solstice, evergreen ivy decorated homes to symbolise eternal life, a practice carried into Christian traditions despite initial church bans due to its pagan roots.

Medicinally, Hedera was a herbalist’s staple, and would be found in apothecaries across the world, the famous seventeenth-century herbalist Nicholas Culpeper recommended infusions or wines of ivy for treating dysentery, jaundice, intestinal parasites, and as a diuretic.

Topically, boiled leaves in vinegar were applied for spleen aches, headaches, ulcers, and burns, and by the 19th century, it was used for rheumatism, gout, respiratory issues like coughs, and skin conditions such as eczema and lice.

In the early 20th century, its efficacy as a cough remedy was ‘rediscovered’ in France and adopted across Europe, including England, the Ancient Greeks, including Hippocrates, knew well its efficacy in preventing intoxication, reducing swelling, and as an anesthetic, influences that reached English practices.

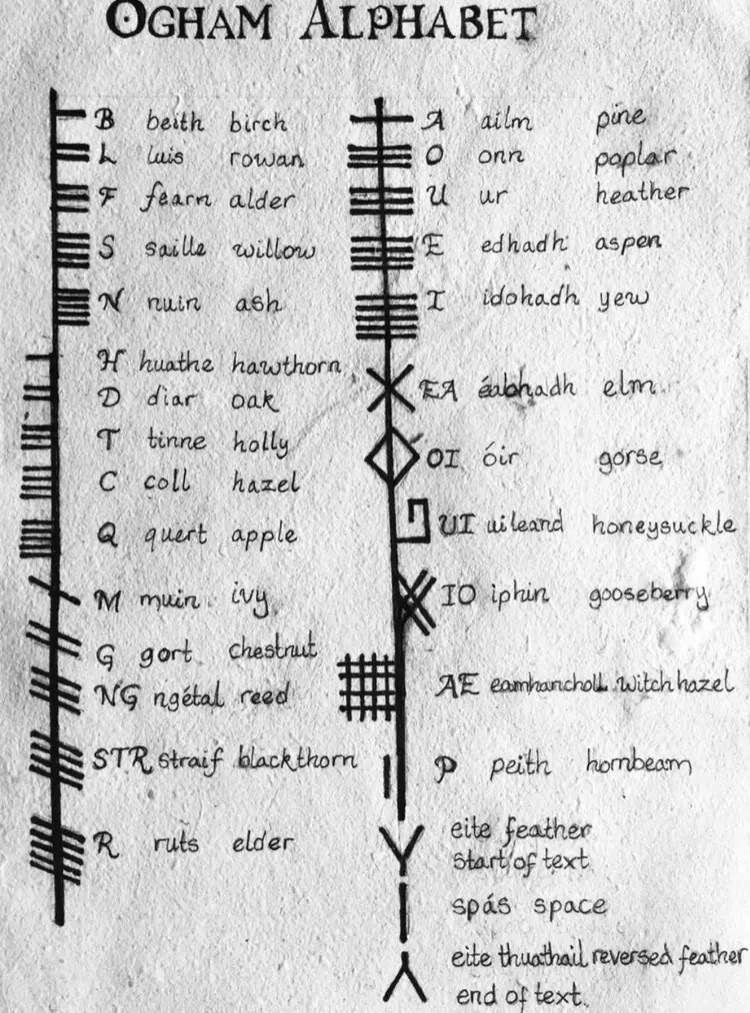

Symbolically, ivy represented fidelity and intellectual achievement; wreaths were given to newlyweds and poets, the Celts incorporated it into their alphabet and associated it with protection.

Ivy in Classical Culture

The ivy’s symbolism of loyalty, immortality, and entanglement has made it a recurring motif in classical literature.

In the medieval Christmas carol ‘The Holly and the Ivy,’ dating possibly to 1710, ivy represents femininity and is paired with holly (masculinity), echoing the pagan solstice traditions where ivy symbolised eternal life amid winter’s barrenness, the carol subtly critiques Christian preference for Holly over ivy, telling us that culturally their roles were intertwined.

In Thomas Hardy’s 1898 poem ‘The Ivy-Wife,’ ivy is personified as a devoted but destructive lover, climbing and ultimately strangling that which it purports to love. His wife Emma, upon reading the poem, became furious with Thomas, thinking that it referred to her, despite his assurances that it was aimed rather at the social climbers that Thomas found himself surrounded by and despised so.

The Ivy-Wife

I longed to love a full-boughed beech

and be as high as he:

I stretched an arm within his reach,

and signalled unity.

But with his drip he forced a breach,

and tried to poison me.

I gave the grasp of partnership

to one of other race—

A plane: he barked him strip by strip

from upper bough to base;

And me therewith; for gone my grip,

my arms could not enlace.

In new affection next I strove

to coll an ash I saw,

and he in trust received my love;

till with my soft green claw

I cramped and bound him as I wove…

such was my love: ha-ha!

By this I gained his strength and height

without his rivalry.

But in my triumph I lost sight

of afterhaps. Soon he,

being bark-bound, flagged, snapped, fell outright,

and in his fall felled me!

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Dec 2025)