A Brief Look at the History of Whalley’s Cistercian Abbey

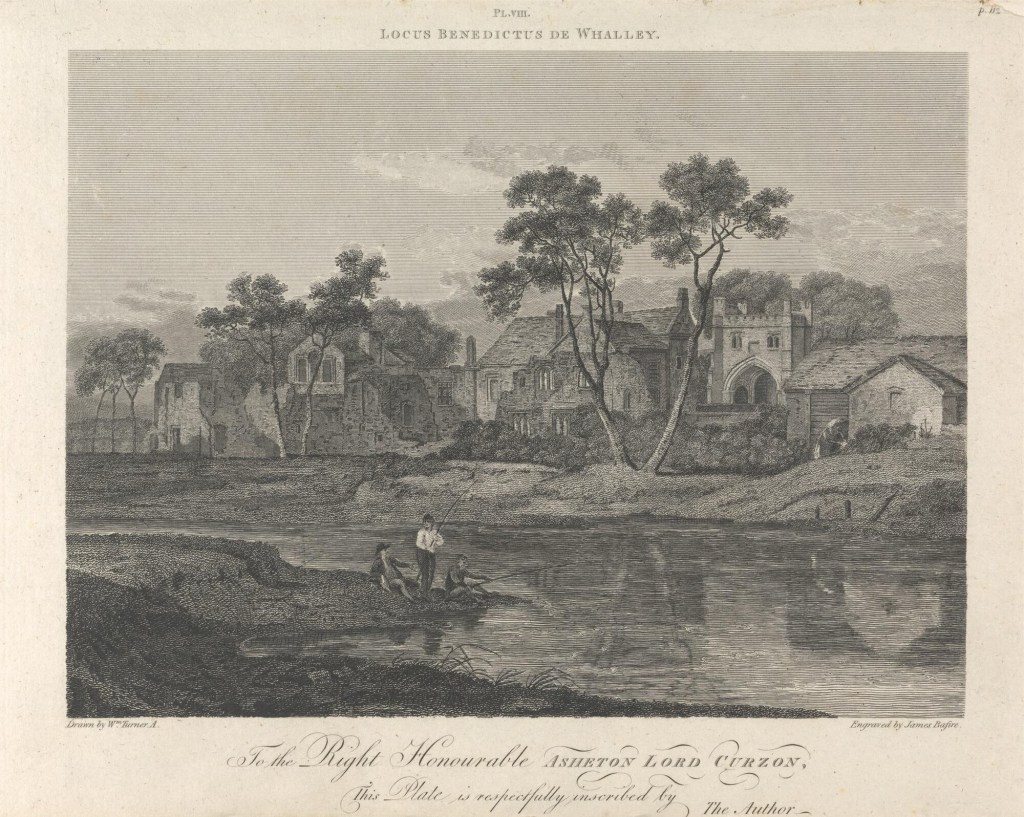

The ruins of Whalley Abbey stand on the northern bank of the Calder in Lancashire’s Ribble valley and were once the second-richest in the county.

Their origins trace back to Stanlow (or Stanlaw) Abbey in Cheshire, which was founded around 1172 to 1178 by John fitz Richard, Constable of Chester. This Cistercian house, affiliated with Combermere Abbey, was built on a flood-prone site at the confluence of the rivers Gowy and Mersey. The monks endured repeated disasters: severe flooding in 1279, the collapse of the church tower in a gale in 1287, and a devastating fire in 1289.

Seeking a more suitable location, the community turned to their patron, Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln and 10th Baron of Halton, who owned vast tracts of land in Lancashire. In 1283, de Lacy agreed to the relocation to Whalley, but papal approval and logistical challenges delayed the move until 1296. On April 4, 1296, the monks formally entered their new home. Henry de Lacy laid the foundation stone in June that year, incorporating an existing chapel built by Peter of Chester, the long-serving rector of Whalley parish.

The relocation sparked tension with nearby Sawley Abbey, another Cistercian foundation just seven miles away, which I’ll also write about this year. Sawley complained of lost income and rising costs due to competition for resources. The dispute was resolved in 1305 by the Cistercian general chapter, requiring Whalley to prioritise Sawley in sales and impose mutual punishments for transgressions.

Monumental Monastery

Building the new abbey was a monumental task that spanned over a century with stone quarried from nearby Read and Simonstone. The church was completed by 1380, while the full monastic complex, including cloisters, dormitories, and outbuildings, was not finished until the 1440s.

Key structures included the North-West Gatehouse (begun around 1320) and the North-East Gatehouse (completed in 1480), which served as the main entrance.

Under Cistercian principles of simplicity and self-sufficiency, the abbey thrived by utilising the abundant local resources: stone quarries, coal and iron deposits, sheep and cattle pastures, fisheries, woollen mills, and arable land, and by the early 16th century, it had become one of Lancashire’s richest monasteries. (See here to read about how important sheep were to the Cistercians)

The last abbot, John Paslew (elected around 1507), enhanced the site by reconstructing his lodgings and adding a Lady Chapel, reflecting a degree of luxury that some historians note allowed him to “live like a lord”.

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Whalley Abbey’s monastic era ended abruptly during Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. In 1536, the abbey became entangled in the Pilgrimage of Grace, a northern rebellion against the king’s religious reforms, Abbot Paslew was implicated, possibly reluctantly sworn into the cause, and executed for high treason in 1537, along with two monks.

The abbey surrendered in 1537 and much of the church was demolished, its stones looted and distributed around the county to be incorporated into other buildings, but the domestic buildings survived. In 1553, the site was sold to Richard Assheton of Lever, who converted the remaining structures into a grand Elizabethan manor house, and over subsequent centuries, the house passed through various owners and underwent modifications.

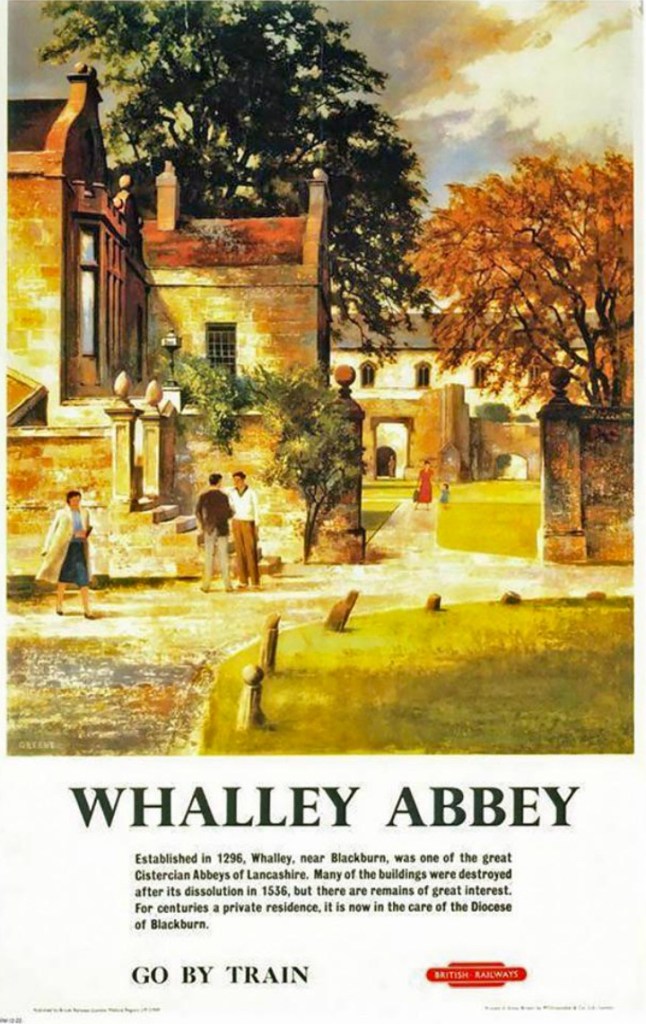

The Abbey Today

In the 20th century the manor house was adapted into a retreat and conference centre for the Diocese of Blackburn, Church of England. The site now offers bed-and-breakfast accommodation, guided tours (in summer), events, and spiritual programs.

Visitors can explore the extensive ruins which are Grade I listed and a Scheduled Ancient Monument, including church foundations (with rare surviving choir pits), cloister ranges featuring ornate carvings and remnants of the lavatorium (washroom), and the impressive gatehouses (the North-West one managed by English Heritage).

Whalley, a Poem by Mervyn Hadfield

When I wur nobbut ten year owd

t’Grandparents took me airt.

We wentter Whalley on the bus

their fav’rite spot, no dairt

As we walked raind the Abbey

I ‘eard story after story

an’, ‘onestly, ah seemed ter see

the site in all its glory.

When t’monks med Whalley thrive an’ grow

fer centuries they ‘eld sway

then ‘Enry th’ Eighth come to the throne

an’ swept ‘em all away.

St Mary’s, t’parish church wur next

I stood in the graveyard theer

teadin’ out folk’s ‘eadstones

an’ wonderin’ if they’d ‘ear

I kept quiet inside t’church itself

(I didn’t even cough)

until mi grandad med mi laugh

an’ grandma towd me off!

Fer ‘e ‘ad whispered in mi ear

‘Yon winder of stained glass

is theer to honour Samuel Brookes

nicknamed ‘Owd Stink o’ Brass’!

Then off ter ‘Whalley Arches’

to look up at the trains

steamin’ over t’viaduct

… that mem’ry never wains

Some said a secret passage ran

from th’Abbey ter t’Dog Inn

I know grandad believed it

‘cos that wur where e’d bin…

… While me an’ grandma ‘ad a brew

when ‘e come back ‘e said

‘I couldn’t find yon passage

so I ‘ad a pint instead.’

Then grandad towd me summat

(I’ve remembered every word)

‘In eighteen-sixty-seven’, ‘e said

‘A great event occurred

Aye, in the world o’ cricket

this village is renowned

First ever ‘Roses Match’ wur played

at Station Road’s owd ground!’

‘E also talked o’ t’Speedway

Dean’s Pleasure Park ‘ad t’track

wi only two bikes racin’

‘e’d been there long years back.

We went ter see ‘Alms-‘ouses’

an’ theer, mi gran towd me

yon row of tiny cottages

as pretty as could be

Wur built fer t’ poor o’ parish

they wur ones who got ‘em

thanks to a wealthy gentleman

kind-hearted Adam Cottam

Last month I went ter London

I stayed wi’ friends down theer

they ‘ad ter show me raind the place

fer I’d get lost, I fear!

We goester t’National Gall’ry

in theer I chance ter see

a portrait of owd Cottam

…‘e seems ter smile at me

Fer a moment I’m a child agen

an’ ‘ear mi grandma say

‘Come wi’ me an’ grandad

it’s our Whalley trip terday’

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Jan 2026)

One thought on “Whalley Abbey”