In the 1932 obituary for a Mr Emmott Stevenson of Padiham, Lancashire, it was noted that his father, widely known as “Harry o’ Roger’s”, had been a prominent figure in his younger days for taking part in the particularly rough local “sport” of clog fighting, also called “purring” (likely from a Gaelic term meaning to scrape or stab).

This vicious activity was once a widespread pastime across industrial Lancashire and other northern mining communities, lasting roughly 200 years from the 18th century into the mid-20th century. It was especially popular among colliers and mill workers, who used it to settle grudges, prove toughness, or even as a semi-professional spectacle with promoters, pub venues, and travelling champions.

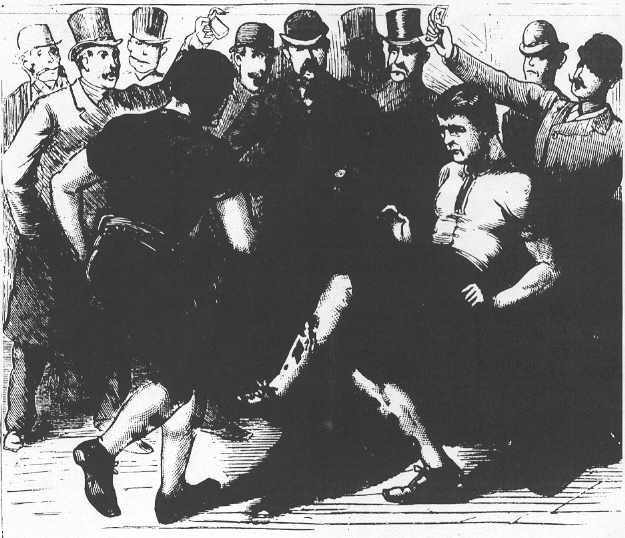

Contestants typically stripped to the waist and fought only with their heavy clogs, wooden-soled shoes reinforced with iron toecaps and studded with sharp nails (called “scads”) for maximum damage. The rules were brutally simple: opponents faced each other, gripped one another’s shoulders for balance, and then unleashed ferocious kicks aimed at the shins. The goal was to make the other man submit through pain, bleeding, or sheer exhaustion. “Corroded” or scarred shins became grim badges of honour among veterans.

Unsurprisingly, clog fighting was illegal, both the violence and the heavy betting that often accompanied it were outlawed, so bouts were held secretly, sometimes in back alleys or behind pubs, with children paid to act as lookouts and warn of approaching police.

The fights could be deadly. There are recorded cases of severe injuries and fatalities, including one infamous incident involving a Wigan collier who was sentenced to 18 months in prison for kicking another man to death with his iron-tipped clogs.

The practice gradually faded after the Second World War, as everyday clog-wearing declined with the rise of cheaper mass-produced footwear in the 1950s, yet memories of “purring” lingered in local folklore well into living memory.

On a brighter note, the traditional Lancashire clog itself has a more enduring legacy. “Old Jack Millward”, from the Hebden Bridge area, was said to be one of the last true hand-crafted clog makers when he died at 85, felling his own trees and crafting each pair from start to finish in the old way.

Remarkably, there is still one dedicated craftsman keeping the tradition alive today: Jeremy Atkinson, widely regarded as the last traditional hand-carving clog maker in the whole of Britain. Working from his workshop in Herefordshire, he creates bespoke clogs the old-fashioned way, carving soles from fresh wood using long-handled knives, attaching leather uppers, and fitting them with irons or rubber soles.

You can see Jeremy in action, and even buy a pair of his clogs, each year at Slaidburn Steam Rally in the Forest of Bowland.

How Traditional Lancashire Clogs are Made

Once the universal footwear of the Industrial Revolution’s Cotton mills, coal mines, and factories, clogs were far more than simple shoes, they were tough, practical, and built to withstand wet floors, heavy labour, and long hours on your feet. Unlike the fully wooden Dutch sabots, British (and especially Lancashire-style) clogs featured a carved wooden sole paired with a leather upper, making them more shoe-like and comfortable for extended wear.

The craft peaked from the 1840s to the 1920s, with thousands of clog makers in northern England. While many later used machines for rough shaping, the purest traditional method, still practised by a handful of artisans like Jeremy Atkinson, relied almost entirely on hand tools and green (freshly cut, unseasoned) wood.

Step-by-Step: The Traditional Handmade Process

Sourcing the Wood

The sole started with carefully chosen timber, Lancashire cloggers often favoured Alder (soft, water-resistant, and moulded to the foot over time, mill workers loved reusing old alder soles with new uppers!), sycamore (durable and longer-lasting), Birch, or willow. Young trees (20 to 30 years old) were preferred, felled green, and split along the grain to avoid splitting during drying.

Here’s a glimpse of traditional clog-making workshops and tools in action:

Rough Shaping the Sole

Using a froe to split the log, then a massive stock knife (or “blocker”), a razor-sharp blade up to three feet long, pivoted from the workbench for leverage, the maker carved the rough sole shape from green wood. This was done following the grain for strength and to prevent cracking.

The iconic curved Lancashire sole was hollowed out underneath (for lightness and flexibility) using specialised hollower and gripper knives to create the rebate (groove) where the leather upper would attach.

Seasoning and Finishing

The roughly shaped blocks were stacked to air-dry for months. Once seasoned, finer tools (rasps, short knives) smoothed the surface, refined the fit, and ensured the balance point sat just behind the ball of the foot for natural walking.

Crafting the Leather Upper

Thick leather (often waxed kip from Indian water buffalo or similar tough hides) was cut to pattern, stitched into uppers (vamp, quarters, and sometimes a heel stiffener), and dyed by hand. The leather was stretched over a last (a foot-shaped form) using pincers and a heated tool to soften and mould it, then tacked onto the sole with brass or steel welt tacks over a leather strip for a secure join.

Final Touches: Irons and Protection

To prevent rapid wear on rough surfaces, clog irons (or “cokers”), metal strips or horse-shoe-like bands, were nailed to the toe and heel. Some had brass toe caps for extra protection (or shin-kicking!). In later years, rubber soles or “rubber irons” became popular for quieter wear.

The entire process for a hand-carved pair could take around eight hours of skilled work (plus drying time), producing footwear that was cheap, repairable, warm, and waterproof, perfect for the damp, gritty world of Lancashire’s mills.

Though factory-made soles later sped things up, the handcrafted version lives on in the work of dedicated makers preserving this endangered craft.

The Doffer

Penned by Joel G Whittaker and published in the Colne and Nelson Guardian in May 1864

Away from the din of the loom-

Ascend the winding stair –

Peep you into the Throstle’s room

Where Lancashire lasses all in bloom,

Are working free from care.

Closely you watch the spindle band

With eager scruting

Till thrust aside by nimble hand

And “aot o t’gate” you’re told to stand,

While Doffers hurry past.

They are a yelling, shouting crew –

Their legs and arms ar bare –

Fast as they can they scamper through,

Little’s the heed they take of you

Except to turn and stare

There’s nought they like as much as fun,

A plaguey lot are they;

Their “bufflers” shouldered on they run

Eager to get their Doffing done

And then run out to play

Excitement lights up every face

On every brow ‘tis seen,

Some youthful “Deerfoots” try their pace

a penny for he who wins the race,

Each vows he’ll not give in!

Or some, less peacefully inclined

Arrange a warlike sight,

Some of the lads have a martial mind,

A nook that’s partly hid they find

And gird themselves to fight.

The boyish warriors then enlist

Their clogs with iron bound,

And if they’re felled by foeman’s fist

None upon either side desist

But fight upon the ground.

While thus the mimic war is waged

Outside the factory door,

A man comes forth – and much enraged

Seeing the Doffers thus engaged

And many in their gore.

Heedless he rushes in the rowd

Of angry fighting boys;

They heed him not – his question loud –

“What are yo’ fightin’ for i’t’foud”

Is lost amid the noise.

Alas! That he has thus premused

He soon has cause to mourn,

all, all in vain he stormed and fumed,

Soon he regrets the part assumed,

On him the Doffers turn!

All their united force is used

Against the luckless wight,

By twenty clogs his shins are bruised –

Thoughts of defence are all confused

And prudence urges flight.

By forty nimble feet pursued

He gains the factory door,

when safe within he vows more shrewd

“ Sin’ Doffers canna’ be subdued

O’ll interfere non moor.”

Such once were they, who’re born, are bearing now

Privations ‘neath the frown on privations brow,

Such once were they, long ere the cotton dearth

Brought woeful want to many a humble hearth,

Such once were they, whose lofty fortitude

Famine and nakedness has not subdued,

But who, through suffering, gaunt and chill

Have nobly striven, and are striving still,

Have shown to wondering nations through these long,

Hard years, that they can suffer and be strong.

This poem was, as can be deduced from the last few stanzas (long ere the cotton dearth) and (through suffering, gaunt and chill) was written at the heart of the Cotton Famine, a ‘doffer’ is a young boy employed to remove and replace the bobbins and spindles in factories.

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Jan 2026)