Biology and Ecology of the Peat-forming Plant Species Sphagnum Moss

Up to now I have published over 400 articles on various topics, many of them about our uplands and the wildlife that lives upon them. I have written about Cottongrass and Curlew, Emperor Moth, Hen Harrier and many more, but, as of yet, I have not written about what I would argue is the most important, a plant without which most of those species would have no home, and that is the common and widespread bog-building moss: Sphagnum.

I know from experience that such bogs can be treacherous, as the seemingly solid surface will in fact be a spongy layer of plant matter floating on top of an unknown depth of water (Agnes Monkelbaan)

Sphagnum moss belongs to the genus Sphagnum, comprising over 30 species in the British Isles, many of which can be very challenging to distinguish.

These non-vascular plants lack true roots and absorb water and nutrients directly through their leaves. Each plant features a main stem with clusters of branches and leaves containing two cell types: small green chlorophyllose cells for photosynthesis and large, clear hyaline cells that store water, thus enabling sphagnum to hold up to 20 times it’s dry weight in water.

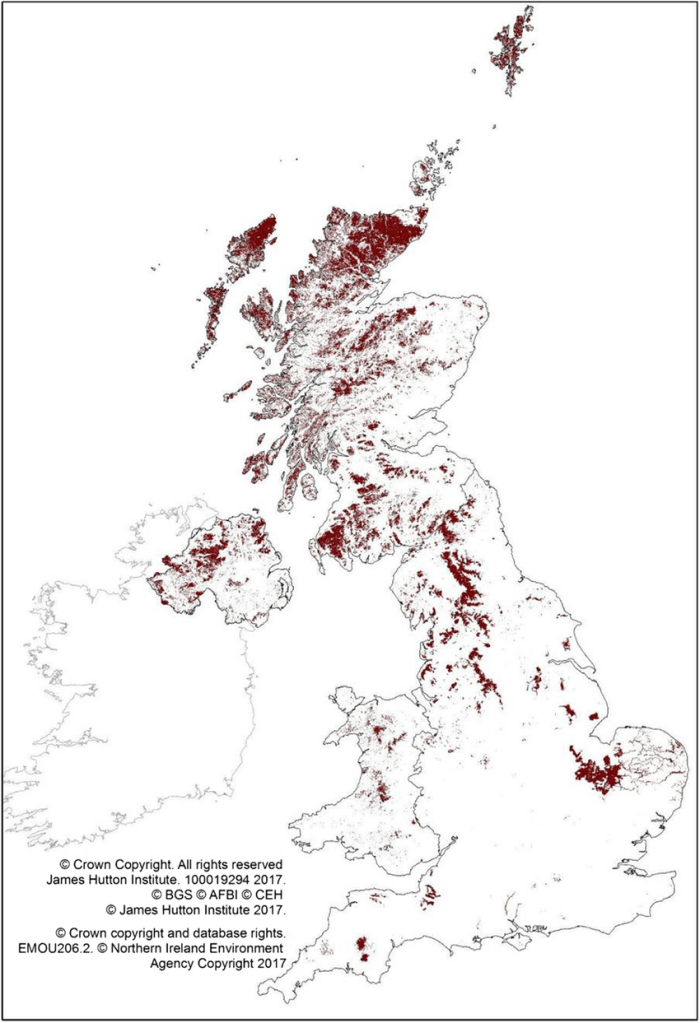

It thrives in wet, acidic, nutrient-poor environments such as blanket bogs, raised bogs, fens, marshes, heathlands, and moorlands. Blanket bogs, most often found in upland areas with high rainfall (typically above 200m elevation), cover vast landscapes in places like the Forest of Bowland, the Pennines, Peak District, Scottish Highlands, and parts of Wales and Northern Ireland.

Raised bogs, dome-shaped and isolated from groundwater, occur in lowland areas, including the Central Belt of Scotland, Solway region, the ‘mosses’ of north-west England, and Northern Ireland.

Widespread but localised to wetlands, some species of Sphagnum are rarer and protected, such as Sphagnum balticum (Baltic bog-moss), listed under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and a Priority Species.

Bog Building

Peat formation in Britain is predominantly driven by sphagnum moss in blanket and raised bogs, where organic matter accumulates faster than it decomposes due to waterlogged, acidic, low-oxygen conditions.

Sphagnum itself encourages these conditions through a complex and one could almost say selfish process. Firstly, through cation exchange, it absorbs nutrients like calcium and magnesium while releasing hydrogen ions, acidifying its surroundings (often to pH 3 or 4). This, along with phenolic compounds and organic acids in its cell walls, slows decomposition and inhibits competitors. Different species occupy specific niches based on water table depth, moisture, and nutrient levels, with some forming hummocks and others carpets or pools.

The process begins in wet depressions or shallow lakes, where sphagnum colonises edges and spreads. In blanket bogs, unique to cool, wet, oceanic climates like our uplands, sphagnum grows over mineral soils under consistently high rainfall. In raised bogs, it develops over former lake beds or fen stages, building upward into isolated domes.

(Andrew Curtis)

Growing vertically, at rates of a few millimetres to centimetres per year, the upper parts of the plant live and photosynthesise, while lower stems die and sink into anaerobic layers. The moss’s hyaline cells release water, maintaining saturation, while acidity and phenolics from cell walls severely limit microbial decay. This preserves plant remains, mostly sphagnum itself, as peat.

Peat accumulates slowly, at about 1mm per year, forming layers metres deep over thousands of years (some of our blanket bogs are up to 9,000 years old). In blanket bogs, sphagnum creates a self-sustaining system: peat holds water, promoting more sphagnum growth and further peat buildup. Key peat-forming species include Sphagnum papillosum, Sphagnum capillifolium, and Sphagnum medium.

This bog-building process results in distinctive micro-topography; hummocks, hollows, and pools, supporting specialised flora like Cottongrass, Heather, Sundew, and Butterwort.

Ecological Importance

As well as providing habitat for rare species our peatlands store around 3.2 billion tonnes of carbon, equivalent to decades of national emissions, making them crucial for mitigating any climate change effects.

Healthy sphagnum-dominated bogs also act as natural sponges, absorbing rainfall to reduce flooding downstream, filter water (much of our drinking water originates in the uplands), and maintain clean streams for species like Salmon, Crayfish and trout.

Uses and Conservation Concerns

Historically, sphagnum was used in wound dressings for its absorbency and antiseptic qualities. Today, peat (largely sphagnum-derived) is harvested for horticulture, though this is declining due to environmental impacts, with bans and alternatives promoted.

Over 80% of our peatlands have been damaged to a greater or lesser degree by peat extraction, drainage and agriculture. Degraded peatlands release stored carbon as CO₂, which is thought to exacerbate climate change, and reduces flood resilience. Peatland restoration efforts, such as those by the Moors for the Future Partnership, involve reintroducing sphagnum to rebuild peat-forming layers and block drains.

A Confession

I feel I must confess here that my first proper wage; £100 bound in a crisp blue-and-white paper band, was earned by removing blockages from drains on Waddington fell for the famous Hodder river bailiff and gamekeeper Mick Maudsley.

For one week in the early 90s, during the summer holidays, we removed stones, rushes and other blockages from drainage dykes in order to facilitate draining of the peat, as was recommended practice at the time, and repaired grouse butts, drystone walls and the shooting hut in the photo above.

Nowadays the owner of the land, Robert Parker of Browsholme Hall, has had these ditches blocked up again to encourage re-wetting, as is the current practice.

Of course I was a school-kid at the time and didn’t know any better; it was fun, I learnt a lot from a very interesting character and got a tan and £100 to boot!

A few years later, when I found that sphagnum moss was being harvested from the Woodcock-and- Nightjar-haunted woods behind the gatehouse we rented at Browsholme, to be used in hanging baskets at a nearby garden centre, I engaged in a small act of eco-activism, removing the stack of blue plastic feed-bags that had been left to fill with moss and hiding them in one of the rotting old camo-painted cabins left abandoned in the woods by a failed paintball shooting enterprise.

Naturally this petty act of vandalism didn’t achieve anything; empty feed-bags are ten-a-penny after all, so the moss-harvesters just returned another week with some more bags.

I suppose at the time I was annoyed that someone was disturbing the mossy damp woods that I like to watch the Woodcock rode over in spring, and that I regarded as my own because nobody ever went there, but it transpired that the moss-gatherers only took a small amount from the woodland floor and it grew back very quickly, so I soon came to realise that my anger was completely unfounded.

I suppose that the emotions I felt were quite similar to the ones Roethke expresses in his evocative poem ‘Moss-Gathering’.

Moss Gathering

By Theodore Roethke

To loosen with all ten fingers held wide and limber and lift up a patch, dark-green,

the kind for lining cemetery baskets,

thick and cushiony, like an old-fashioned doormat,

the crumbling small hollow sticks on the underside mixed with roots,

and wintergreen berries and leaves still stuck to the top, —

That was moss-gathering.

But something always went out of me when I dug loose those carpets of green,

or plunged to my elbows in the spongy yellowish moss of the marshes:

and afterwards I always felt mean, jogging back over the logging road,

as if I had broken the natural order of things in that swampland;

disturbed some rhythm, old and of vast importance,

by pulling off flesh from the living planet;

as if I had committed, against the whole scheme of life, a desecration.

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Feb 2026)

One thought on “Sphagnum Moss, The Bog-builder”