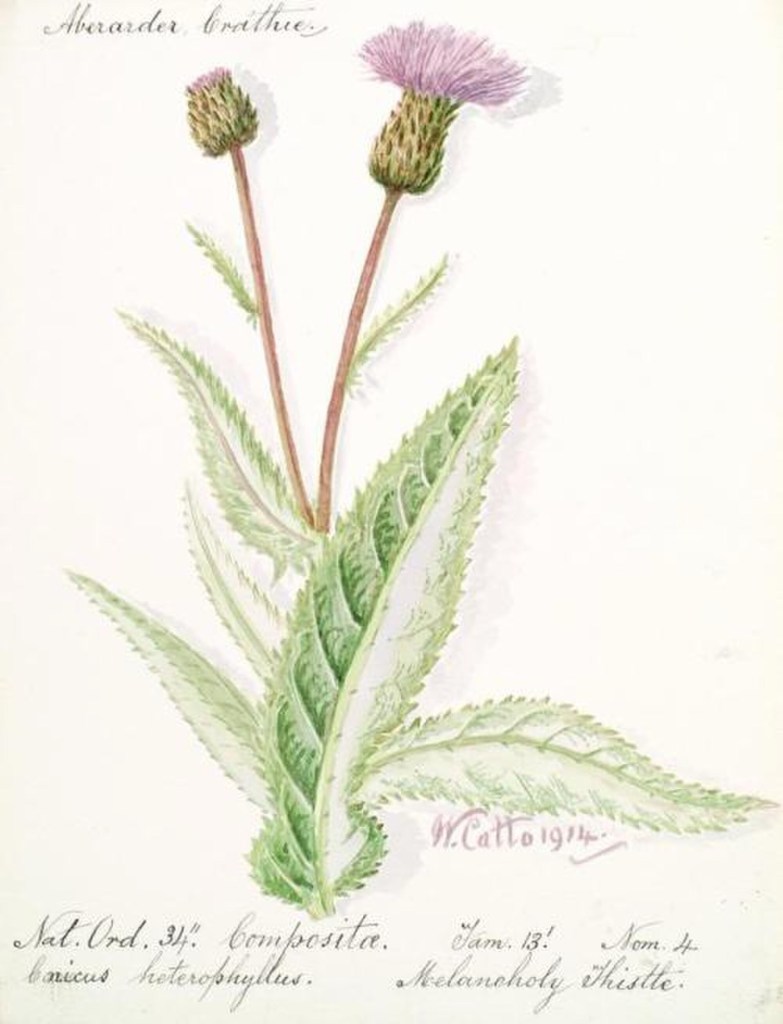

The Melancholy Thistle, Cirsium heterophyllum, Cirsium originating from the Greek word ‘kirsos’, meaning swollen vein which refers to thistles being used as a cure for varicose veins, and heterophylum meaning ‘different leaf’, is a fairly tall thistle with a deeply-furrowed, wooly stem, large flower-heads and soft, downy leaves with an almost felt-like underneath.

It prefers damp, unimproved (unimproved meaning untouched by fertilisers) soils such as hay-meadows, the banks of streams and woodland edges. It was once widespread across the north of England but is now classed as Near Threatened and has only managed to hang on at a few sites which have been managed as wildflower meadows such Bell Sykes meadows near Slaidburn.

Vibrant Purple Flowers

The flowers of the Melancholy thistle usually grow singly on one stem, are around 4cm wide and a vibrant purple colour. They grow from 50cm to 1 metre tall so can be the tallest flowers in a wildflower meadow, towering over other flowers such as the yellow Hayrattle, Orchids or the round yellow flowers of the Globeflower.

They are called the melancholy thistle because they droop when they are first blooming before gradually standing straight up although the 17th century herbalist Nicholas Culpeper viewed the thistle as a cure for melancholia;

“the decoction of the thistle in wine being drank, expels superfluous melancholy out of the body, and makes a man as merry as a cricket; … my opinion is, that it is the best remedy against all melancholy diseases”.

Indeed its flowers has been used in various alcoholic concoctions and the leaves and roots are also edible, though the roots of all thistles tend to create the unwanted side-effect of flatulence so are probably best avoided unless, perhaps, this is the means by which the superfluous melancholia is expelled?

(Andrea Moro)

Propagation

As with other wildflowers the decline of the Melancholy Thistle is largely due to loss of habitat and over-fertilisation of farmland but it does itself no favours in terms of reproduction.

Colonies of this species have found to be mostly clonal, as it produces very little viable seeds and few of these are wind-borne as with other thistle species so it doesn’t spread to new sites very readily.

Recent programmes to establish new colonies of the Melancholy thistle have relied upon collection of seeds by hand and the taking of plugs, (young plants), which are then propagated in a greenhouse and planted at new sites.

This has been done in a way which means that plants from different patches of clones have been mixed, in the hope that concurrent plants will be more genetically diverse and therefore stronger and capable of competing with other, more dominant, species which would usually push it out.

(Robert Flogaus-faust)

Reasons for Decline

As well as over-fertilisation, overgrazing has also been found to be responsible for the decline in wildflower species like the Melancholy thistle, traditionally a hay meadow would be grazed from autumn, through winter until early spring with no grazing stock being left on the hay meadow at all after May, this gave the thistle, and other wildflowers, time to bloom and produce seeds.

In recent decades it has become usual for grazing stock to be kept on a field all year round or for silage to be cut all through the year which stops plants like the Melancholy thistle from establishing themselves.

Roadside verges also used to be a common habitat for the Melancholy thistle and recent trials by councils in reducing mowing of verges has shown that this lets these important strips of possible wildflowers develop into the species-rich verges they traditionally were.

Being visited by Common carder bee (Bombus pascuorum) and Gypsy cuckoo bumblebee (Bombus bohemicus)

(Ivar Leidas)

The Thistles Future

In the summer the bright purple flower-heads of the Melancholy thistle can be enormously attractive to flying insects such as butterflies and bees and they can form a queue reminiscent of planes in a holding pattern as they wait for their turn to land on the single thistle head.

Later in the year its seeds will attract seed-eating birds, including the Goldfinch which I’ve just written about, they will be less polite over who gets to land on the seed-head, being more desperate than the bee or butterfly as they sense winter coming, thus making the thistle an important plant for wildlife nearly all year-round.

This is a sight that should become more frequent over the years with all the work that is being done trying to propagate and reintroduce this and other wildflowers, and once enough of them have been planted it should start spreading of its own accord to become as commonplace in our countryside as it once was.

…Himself beheld three spirits mad with joy

Come dashing down on a tall wayside flower,

That shook beneath them, as the thistle shakes

When three gray linnets wrangle for the seed….

(Excerpt from Guinevere by Alfred Lord Tennyson)

A B-H

(Oct 2024)

Alba!

LikeLiked by 1 person

🏴👍!

LikeLike