‘From Silverdale to Kent sand side,

Whose soil is sown with cockle shells’

From Cartmel eke, and Connyside,

With fellows fierce from Furness fells’

The expansive sands of Morecambe Bay cover over 120 square miles and from their muddy creeks and channels, where flounder abound, to the sandy, silty flats where fields of shellfish can be found, lives a great array of flora and fauna.

In my natural history articles I’ve looked at several of these species, including the Oystercatcher and the Curlew, both of which the bay is an internationally important site for, but I’ve never really looked into the shellfish, which are perhaps the most vital and overlooked creatures of all in this coastal environment.

Morecambe is of course famous for it’s shellfish, indeed it’s name is synonymous with potted shrimps, so much so that it’s football club is even nick-named ‘The Shrimps’! but it has long been known for other seafoods too; Mussels, Scallops and most notably Cockles, which are the subject of this piece.

Busy Bivalves

The Common Cockle Cerastoderma edule, is an extraordinarily busy little bivalve and plays a very important role in its habitat, feeding not only humans but many other animals too, indeed the latter half of its scientific name; edule, means ‘edible’.

Their presence by the millions just under the surface of Morecambe bay’s infamously glutinous mud have attracted flocks of the afore-mentioned seabirds and others since the mud was first deposited by the retreating glaciers of the last ice-age, some 12,000 years ago, and in this time they have brought crowds of us humans too, as archaeological finds have proven.

Discussing the entirety of this history would be exhausting, and prehistoric records of fishing in the area are thin on the ground anyway (or should it be thin in the ground?), so here I concentrate on Cockle fishing in the last hundred years or so.

(Clive Varley)

Cardiacal Cockles

Cockles live where the mud is nutritious and washed often by the sea, surviving best in the inter-tidal zones where water covers them for around 18 hours a day yet not where they are only covered for at least 3 hours a day, nor if the water is more than half fresh-water.

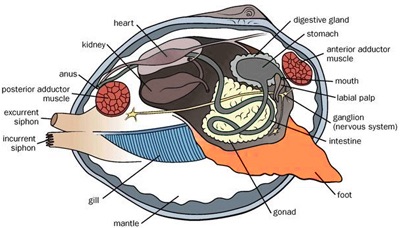

In this littoral land of not-quite-earth, not-quite-sea they can thrive if conditions are right, filtering food from sea-water with long syphons which protrude from the two halves of their shells, the ‘bi-valves’ which their kind are named after.

The family to which the Cockle belongs is called Cardiidae, from the Greek kardia, meaning ‘heart’, and they resemble this organ somewhat in both form and function, pumping in seawater through one syphon and out through the other.

They have three spaces in their mantle to protrude both of these through plus their muscly ‘foot’, which they use for mobility, able to burrow through the sand with surprising speed, and when they withdraw them and pull their shell shut it resembles the classical ❤️ shape when looked at from the side.

This might have something to do with the saying “warming the cockles of my heart” but etymologists, those who study the origin of words, have never been entirely sure, what we do know however is that ‘cockle’ comes from the French word coquille, which in turn comes from the Greek konchylion; as in konche, which you might recognise as Conch.

Chickens and Oysters

The tastiest bit of shellfish like clams and cockles is their muscly yellow foot, in some parts of the British isles this is referred to as the ‘chicken’, which is a tad bit confusing, especially as there are parts of a chicken referred to as the ‘oyster’!

This ‘chicken’ is what makes cockles such nutritious and tasty creatures, and when I lived over in Northern Ireland I was shown a nifty little way of getting to it when you are on the shore without any tools to hand.

The method is called ‘keying’ and involves simply placing the hinges of two cockles together firmly and twisting to prise them open, I was shown this by a couple of lads from Whiteabbey in Belfast.

Some of my friends and cousins used to pop up to Belfast from where I lived further down the coast in Dundrum and if I wasn’t working I’d accompany them, on one memorable occasion my friend had to go off on business so dropped me off to spend the afternoon with a couple of his mates from the area “you’ll be fine with these lads they’re sound enough” he said.

So I found myself walking along the mud of Belfast Lough on a gloriously sunny late summer’s afternoon with two local lads each wearing trainers and tracksuit pants, one carrying a plastic carrier-bag full of cockles and one a rake.

I learnt a lot of interesting nuggets about what was going on in Belfast at that time (around 2002/3) and what it was like growing up there and as we walked along they would occasionally reach into their cockle bag and pull out a couple, they would then stick the two cockles together and twist them.

One of the lads had a table-salt shaker in their pocket, “sure it’s my ma’s”, and they would sprinkle a bit on the yellow foot, bite it off and then chuck the rest of the cockle away on the sand “you only eat the chicken cos the rest has all the shite in it”,

I learnt a long while afterwards that just down the coast from where we were eating these cockles are the run-off pipes from Belfast’s old landfill tip.

Fishery closures

Pollution is a huge problem for shellfish fisheries, I know first hand how much of a financial hit it is for a fishery when they have to close because of a pollution alert having worked at a fishery myself for a while.

This was Dundrum Bay Fishery where we only picked Oysters and Mussels and the pollution alert was due to overflow from the local sewage works. I only worked there occasionally when I was called to ask if I would like to help out for a bit of extra cash. It affected the small family-run business hugely, especially its handful of full-time staff, with repercussions for the village as well, being one of its only employers. (I’ll write about these experiences in a future series called ‘Up in Down’)

Back over on this side of the Irish Sea and back to the present Morecambe bay is itself regularly polluted by sewage, but in recent years the main cockle bed, at Flookburgh, has been closed by the North Western Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (IFCA) not because of pollution but after surveys found that cockles sampled were of too small a size with too low a percentage of adults to allow permits to be issued.

Although toxins from sewage may make cockles dangerous for consumption research has shown there to be a link between cockle size and mortality, put shortly they don’t grow big enough or long enough to eat if the water is too clean, as there is nothing for them to eat.

The legal cockle trade in Northwest England before Morecambe bay’s closure was estimated to be £7 to 8 million out of the UK total of £20 million, according to the Shellfish Association of Great Britain, last year Morecambe Bay’s contribution to this figure dropped to £90,000 but is predicted to recover to £2 to 3 million when it opens up again. As of writing this re-opening is pencilled in for July the 1st 2025 but I’ll update this article when I can find out for certain.

(Roger Geach)

Craams and Jumbos

In the main most cocklers still gather them the old way, essentially just raking them from the sand, and when the fisheries reopen they will be out once more with their Jumbos and Craams doing just this, this is how they go about it;

First the cockler will head out on a suitable vehicle (nowadays a quad bike or tractor but historically on horse or donkey-back) to the cockle beds, those that have been doing this for generations will know exactly where to go, having in their heads a map, both physical and temporal, of the tides, weather and ever-shifting sandbanks and channels, those new to the area may follow their tracks.

Once they reach their goal, sometimes over a mile out on the sands, all the time keeping one eye on the infamously treacherous tides, which come rushing in at over 9 knots and always behind you whichever you face, they immediately get to work.

To soften the sand and get the cockles to the surface from their usual home up to 5cm down I they first ‘rock their jumbos’, these are long boards with handles at each end;

You and me (who can take up to 5kg of cockles before needing a permit) might use a garden rake with a shortened handle to gather up these cockles but a proper cockler uses a ‘Craam’. With this archaically named hand-tool they deftly pick and rake the cockles out, a class 3 permit has to be obtained from the NWIFCA for using one of these though as they only pick out the biggest cockles, which take over 4 winters to grow.

A riddle or sieve may then be used to sort through the cockles ensuring that only the right size ones are harvested;

Nowadays the cockles will be collected into nylon sacks, weighing 25 kilos with up to 2000 cockles per bag, but until not long ago they would have used baskets called ‘tiernals’, then these will be thrown onto trailers to race back to shore before the tide comes back in, it’s very hard back-breaking work and you can tell the old cocklers from the stoop they develop after years of doing this in all weathers and conditions.

Flookburgh’s Fishing Families

Although it’s been an important industry in the area for hundreds, maybe even thousands of years it was really in the 19th century that cockling really took off.

This was due to the arrival of the railways to the area which opened up new markets and some local families were sharp to jump on this money train, especially in the ancient village of Flookburgh on the Cartmel peninsula.

In this tiny village there used to be over 20 families that worked solely on the cockle beds, but now there are only a handful and cockling is not a main source of income for any of them, being more of a welcome opportunity for making some extra money to be jumped upon whenever the authorities permit it.

Strangely enough these cockles are hard to buy locally, unless you know which doors to knock on, instead they are whisked off to foreign markets.

Carted off to the Continent

British people don’t really like Cockles anymore it seems, tastes change and the old days, when cockle and winkle sellers would tour pubs touting their fishy wares, are sadly long gone.

Instead most of our cockles are carted off to the continent instead, mainly via ferry to Holland, then to countries that have overfished their own cockle beds so must now look elsewhere.

Middle-men will arrive to collect the bags of fresh shellfish straight from the cocklers, they will then drive straight across the country in refrigerated vans to the channel to meet a ferry.

Once on the continent they will be immediately sold to buyers who will then clean and pack the shellfish in EU-approved premises, and within 24 hours they will have been bought by French, German or Spanish fishmongers or restaurateurs who, unlike most of us Brits, appreciate the subtle taste and versatility of a good fresh cockle.

At one point this demand for British cockles became so fierce that organised criminals got involved and used gangmasters to source labour to pick them. Tragedy struck in 2004 when undocumented Chinese pickers, untrained, inexperienced and with no knowledge of how dangerous the tides and quicksands of Morecambe bay are, came into trouble leading to the deaths of 23, you can read a bit more about the Cockle Picker’s Tragedy here.

Because of this cockle picking in Morecambe bay is now highly monitored and regulated.

Of course you can still buy them in this country though we prefer them pickled in jars from companies such as Parson’s Pickles, who sell about 2.5 million jars a year to major supermarkets, occasionally you may see them for sale in fishmongers and on the counter of your local chippy, in Morecambe itself Edmondsons Fresh Fish sometimes stock them but if not they do specialise in potted shrimps which are equally tasty so you won’t come away empty handed.

To finish here’s a little tale, probably apocryphal, telling of the time cockles caused a church split;

“Once a clergy-man near Morecambe Bay complained that half his parishioners had left him. The local industry was cockle-gathering and the animals had moved from the shores bounding his parish to others across the Bay, whither his parishioners had followed them”!

A B-H

(Nov 2024)

Fascinating.

Put an order into Parsons Pickles.

LikeLiked by 1 person