(Chris Heaton)

Hidden away deep in the Forest of Bowland, sagged and slumped under the weight of time and overgrown with mosses, ferns and lichens, lie relics of a once great industry; the manufacture of Quicklime.

These unassuming structures, now mostly reclaimed by time and nature, were once vital to the agricultural and economic life of the region, and though their prominence has faded from memory, they offer us at least a glimpse into a bygone era of rural industry and ingenuity.

Quicklime

Limekilns were once a much more common sight across the landscape of Bowland, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries when agriculture dominated the region’s economy.

They were built to produce quicklime, Calcium Oxide (Chemical symbol CaO), a versatile substance created by heating limestone in a process known as limeburning.

Quicklime was a precious commodity for farmers, used primarily to improve acidic soils by spreading it across fields to raise pH levels, thus enhancing fertility. It also found use in construction, as a key ingredient in mortar for building the villages, farms and churches that still dot the area today.

How limekilns worked

The abundance of limestone in Bowland made it an ideal location for this industry.

Small kilns, known as ‘clamp kilns’ in their earliest forms, were constructed near outcrops, such as at Whitewell and Sugar Loaf Hill (pictured above) in the Hodder valley, they supplied local farmers and allowing them to process the stone on-site.

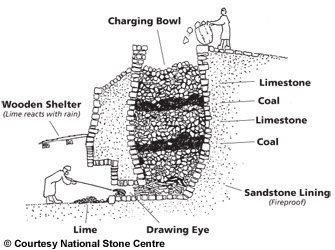

These kilns were simple, often consisting of a stone-lined pit or a basic arched chamber, fueled by wood, charcoal, or later coal, and the process was very labor-intensive;

First, a ‘charge’ of furze or other flammable material was placed within the kiln and ignited, air would be drawn in from the base through an eye or draw hole. The draw holes also allowed more air in if required or could be blocked to slow the burning down.

Once lit the fire had to be constantly monitored and controlled, with layers of fist-sized limestone rocks gradually added (it is essential that the rocks be of the right size as they won’t heat through if too large) along with layers of firing material to keep the chamber burning, three to five layers of stone to one layer of firing material being the ideal ratio.

A burn could take two or three days and the lime had to cool before being drawn off, the result was a fine, white powder; Quicklime.

Important Assets

By the 18th century, limeburning had evolved from a rudimentary practice into a more organised endeavor. Local builders and joiners were often hired to construct more permanent kilns, many of which still stand today.

Historical records, such as the diary of Sedbergh farmer Robert Foster, 1782 to 83, reveal the cost of such projects; 50 shillings for the builder and 30 shillings for assistants, underscoring their value to the community.

Farms with access to limestone and a kiln became highly prized, with the kilns often advertised as assets in property listings, reflecting their economic significance.

The kilns weren’t just practical though, they shaped the social fabric of rural life too. The intense heat they generated, sometimes reaching over 1,000°C, drew weary travelers and tramps seeking warmth on cold nights. Yet, this warmth came with risks.

In an era before modern safety regulations, accidents were common, with horses, workers, and even the occasional wanderer tumbling into the fiery pits or succumbing to the fumes, often with fatal results.

Limekiln Landscape

The Forest of Bowland, with its rolling fells and secluded valleys like those of the Hodder and Loud, is dotted with the remnants of these kilns.

Some, like those at Arbour Quarry in Thornley, grew into larger commercial operations during the 18th and 19th centuries, producing lime on a scale that supplied not just local farms but also neighboring regions.

Early photographs show these kilns as substantial structures, built into quarry faces, their stone arches and chambers a testament to the craftsmanship of the time. Others, such as those along the Trough of Bowland, were smaller, serving individual farms and blending seamlessly into the rugged terrain.

Today, many of these sites are overgrown or collapsed, their stones scavenged for other uses. Yet, for those who know where to look, telltale signs remain; a curved wall here, a sunken pit there, or the faint outline of an arch obscured by moss.

In places like the Brennand Valley or near Slaidburn, walkers might stumble across these relics, their quiet presence a stark contrast to the bustle they once supported.

Scaling up

The heyday of on-farm limekilns began to wane in the late 19th century. The rise of commercial lime production, coupled with improved transport links like railways and canals, shifted the industry away from small, localized operations.

Large-scale kilns, such as the Hoffmann Kilns near Settle and Bellman Park near Chatburn (pictured below), which was the predecessor to the modern day Hanson Cement works, could produce lime more efficiently and distribute it across wider areas.

As farming practices modernised and chemical fertilisers emerged, the need for traditional limeburning diminished, leaving the kilns to fall into disuse.

By the early 20th century, most of Bowland’s limekilns had been abandoned. Some were dismantled, their stones repurposed for walls or buildings; others were left to the elements, slowly eroding into the landscape.

The industry that had once been a lifeline for farmers slipped from folk memory, preserved only in the work of local historians and enthusiasts.

Link to the past

In recent years, efforts have been made to document and celebrate this lost chapter of Bowland’s history. Books like Limekilns and Limeburning; Around the Valleys of Hodder & Loud, by Frances Marginson and Helen Wallbank available from Slaidburn archives, have shed light on the scale and significance of the practice, drawing on archival research and oral histories.

These works highlight not just the technical aspects of limeburning but its role in shaping the region’s identity, a story of resilience, adaptation, and connection to the land.

For visitors to Bowland today, the limekilns offer a tangible link to this past. A walk through the Trough of Bowland or along the River Hodder might reveal one of these structures, standing as a silent sentinel amidst the wild beauty of the fells.

They are more than just ruins; they are monuments to a time when the landscape itself was a resource, worked and reworked by human hands to sustain life.

To find out if there is a limekiln near you why not check out this excellent and meticulous database of surviving limekilns by historian David Kitching.

A B-H

(March 2025)

Very interesting article and photos too. I see old limekilns all the time where I live, they are just so much part of the landscape.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have that book Limekilns and Limeburning Around the Valleys of Hodder and Loud and have visited most of them. Your link to David Kitching’s site is a bonus.

LikeLiked by 1 person