In the latest addition to my Unnatural Histories collection I return to a part of Lancashire I grew up in to look deeper into the background of a ghost story we heard many times as children.

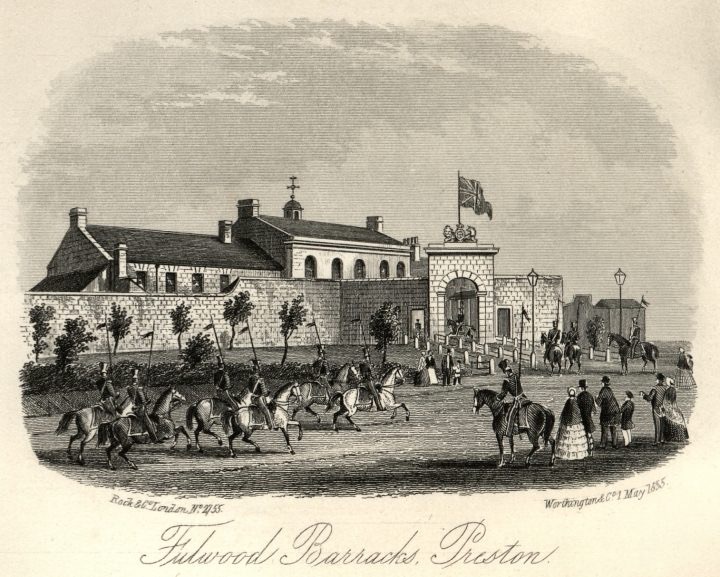

It is a tale of murder, trial, execution and haunting, and was made even more chilling for us as our tall red-brick town-house directly faced the black gates of the barracks it occurred in.

(Preston Digital Archive)

Private Patrick McCaffery

Born in October 1842 in Athy, County Kildare, Ireland, Patrick McCaffery came from a fractured family. His father, also named Patrick, was dismissed from his role as governor of Carlow Lunatic Asylum amid scandal and emigrated to America, leaving young Patrick alone in deep poverty, exacerbated further by the Irish Potato Famine.

By the age of 12, Patrick found himself working in the cotton mills of Mossley near Manchester, and later drifted to Liverpool where he had minor run-ins with the law. In October 1860, at just 18, he enlisted in the British Army, joining the 32nd (Cornwall) Regiment of Foot and being posted to Fulwood Barracks for training with the 11th Depot Battalion.

Fulwood Barracks, built between 1842 and 1848 amid fears of Chartist uprisings, was a stern military depot housing various regiments. McCaffery, described as short (5’6”), fair-haired, and reclusive, struggled as a soldier. He was unpopular, often drunk, insubordinate, and frequently punished with confinement, pack drills (marching with heavy loads), and even having his head shaved.

His superiors included the strict Colonel Hugh Hibbert Crofton, a 47-year-old Crimean War veteran, and Captain John Augustus Hanham, a 38-year-old adjutant known as a domineering martinet who had been wounded in the Sikh Wars and the Indian Mutiny.

Tensions boiled over on Friday, September the 13th, 1861. While on sentry duty outside the officers’ quarters, McCaffery was ordered by Captain Hanham to take the names of children suspected of breaking windows. He obtained only one name, leading to charges of neglect and slovenliness.

The next day, September the 14th, Colonel Crofton sentenced him to 14 days’ confinement to barracks, including grueling pack drills.

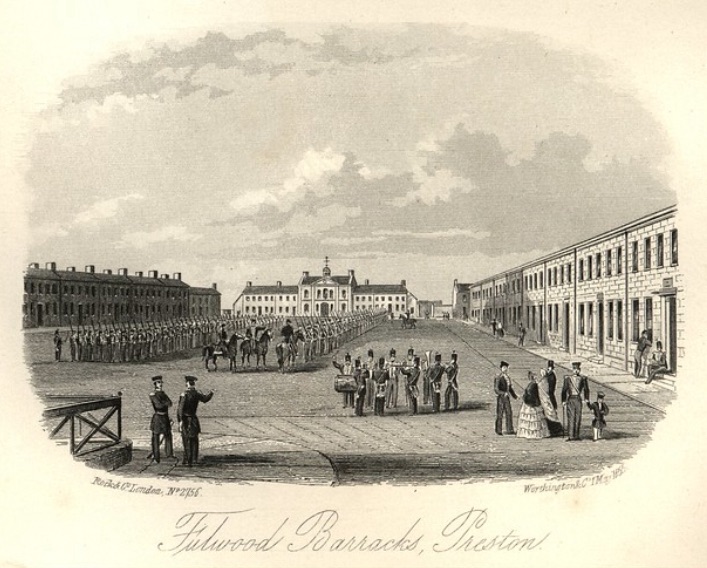

(Preston Digital Archive)

Murder on the Parade Square

That same morning, around 11am, McCaffery was cleaning his Enfield Pattern 1853 rifle outside K Block (now demolished) when he spotted Crofton and Hanham crossing the Infantry Square. In a fit of rage, he loaded his rifle, knelt, and fired from about 65 yards.

The first cap misfired, but he replaced it and shot again. The bullet pierced Crofton’s right breast, passed through his lungs, then hit Hanham’s left arm before lodging in his spine. Crofton exclaimed, “Oh my God, I am shot!” and staggered to his quarters with help, dying at 9:08pm the next evening from choking on blood. Hanham died on Monday, September the 16th, at 11:30am.

McCaffery surrendered immediately, handing over his rifle and reportedly saying he intended to kill Hanham but not Crofton.

The incident shocked Preston and made headlines across England and Ireland, heightening the tensions that already existed between Irish recruits and British officers amid post-famine resentment.

(Preston Digital Archive)

Trial and Execution; A Public Spectacle

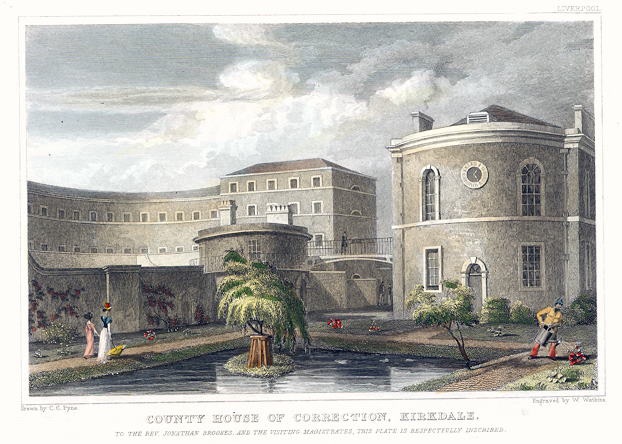

McCaffery was tried at the Liverpool Assizes on December the 12th, 1861. Defended by Charles Russell, he argued no premeditation, suggesting manslaughter, but his courtroom admission “I did not intend to shoot the Colonel but the Captain” sealed his fate. The jury took just 10 minutes to convict him of willful murder. Sentenced to death, he was executed on January the 11th, 1862, outside Kirkdale Gaol in Liverpool.

The execution drew a crowd of 30,000 to 40,000, many sympathetic to the young Irishman. Accompanied by priests, McCaffery kissed a crucifix, prayed, and was hanged by William Calcraft using the short-drop method, which caused prolonged suffering, he struggled for nearly an hour before death. His last words: “Blessed Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, I give you my heart and soul. Jesus and Mary, have mercy on me!” The crowd shrieked and wept, hissing at the hangman. McCaffery was buried within the gaol.

Hanham’s funeral was met with disdain, Preston residents turned their backs on his coffin, and there weren’t enough volunteers for a proper salute.

Engraved by W. Watkins after a picture by C. Pyne, published in Lancashire Illustrated, 1831

The Ballad of Private McCaffery

The story inspired “The Ballad of Private McCaffery,” a deeply subversive folk song rumored to have been banned by the British Army for encouraging defiance. Circulated orally among the Irish diaspora in the North West, it portrays McCaffery as a martyr victimised by tyranny, and warns officers to treat their men decently.

Here are the full lyrics as preserved by the Lancashire Infantry Museum:

When I was eighteen years of age

Into the army I did engage

I left my home with a good intent

For to join the thirty-second regiment

While I was posted on guard one day

Some soldiers’ children came out to play

From the officers’ quarters my captain came

And he ordered me for to take their names

I took one name instead of three

On neglect of duty they then charged me

I was confined to barracks with loss of pay

For doing my duty the opposite way

A loaded rifle I did prepare

For to shoot my captain in the barracks square

It was my captain I meant to kill

But I shot my colonel against my will

At Liverpool Assizes my trial I stood

And I held my courage as best I could

Then the old judge said, Now, McCaffery

Go prepare your soul for eternity

I had no father to take my part

No loving mother to break her heart

I had one friend and a girl was she

Who’d lay down her life for McCaffery

So come all you officers take advice from me

And go treat your men with some decency

For it’s only lies and a tyranny

That have made a martyr of McCaffery

The ballad takes liberties, omitting some details like McCaffery’s poor record, but captures the folk sympathy for him as an orphan wronged by harsh superiors.

Hauntings at Fulwood Barracks

While McCaffery was executed miles away in Liverpool, legends claim his spirit returned to Fulwood Barracks, particularly haunting the old Officers’ Mess in Block 57 (now part of the Lancashire Infantry Museum). Generations of soldiers have blamed unexplained noises, apparitions, and eerie events on him, seeing it as revenge against his tormentors.

However, the museum’s records clarify that while McCaffery’s legend is popular, there’s no direct evidence linking him to the specific ghosts reported.

Indeed the Barracks have their own documented hauntings dating back to the early 20th century including;

The Phosphorescent Figure

In February 1910, an officer awoke to a phosphorescent figure standing by his bed in a ground-floor room, wearing a belt-like item. It faded away, and the terrified officer fled. Similar sightings occurred in 1911 and 1912, with one officer drawing his sword at a figure in the passage. A chaplain investigated and performed prayers, linking it possibly to an older tragedy in a cavalry mess.

The Chapel Poltergeist

A friendly but mischievous presence in the Garrison Chapel of St. Alban (built above the entrance archway, one of the oldest military chapels in use). Cleaners reported items moving overnight, a brass pot flying across the room, and a TV crew, filming a segment for a show about hauntings in Lancashire, had their camera malfunction whenever they tried to film near the pulpit.

Ghostly Romans

On stormy nights, ghostly Roman soldiers have been seen marching waist-high across the parade square along the ancient route of Watling Street, their lower halves invisible due to centuries of soil buildup.

These tales persist today, and the barracks (now home to the museum) attract ghost hunters from all across the world, with some psychics claiming to sense unrest near the old mess, attributing it to McCaffery’s unresolved anger.

If you’re in Preston, a visit to the Lancashire Infantry Museum might let you experience these chills for yourself, and you might appreciate why it was so spooky growing up at number 229!

(Btw if the current residents of 229 read this thank-you for keeping the tall fir tree in the garden and not chopping it down, I planted that with my dad around 1985!)

If you enjoyed this article please consider showing your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Oct 2025)

Great story and info, I’ve actually visited Fullwood many moons ago, for one day, love all the old military establishments.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank-you, yes I’ll have to visit the museum, I’m not really into militaria but it sounds very interesting none the less

LikeLiked by 1 person