Introducing a new series, in which we delve deep into Lancashire’s long coal mining history and the communities shaped by it

Lancashire has a long history of coal mining, dating back to the early Roman era at least, with small-scale exploitation of shallow seams and natural outcrops being archaeologically evident throughout the county.

The use of coal for heating and smithing was widespread but remained a domestic or cottage industry for centuries until the black rock’s full potential was realised and unleashed to great effect.

By the Middle Ages (roughly the 5th to 15th centuries), small-scale mining had become more established. Shallow pits, often little more than bell pits or adits, supplied local households, Limekilns, and early industries. Records from the 13th century mention coal extraction in places like Burnley in northeast Lancashire, while in the southwest, coal was an “unexceptional commodity” traded locally by the 16th century. Landlords sometimes allowed tenants to dig coal for domestic use, and small ‘folds’ (hamlets) in valleys dotted the landscape with rudimentary pits.

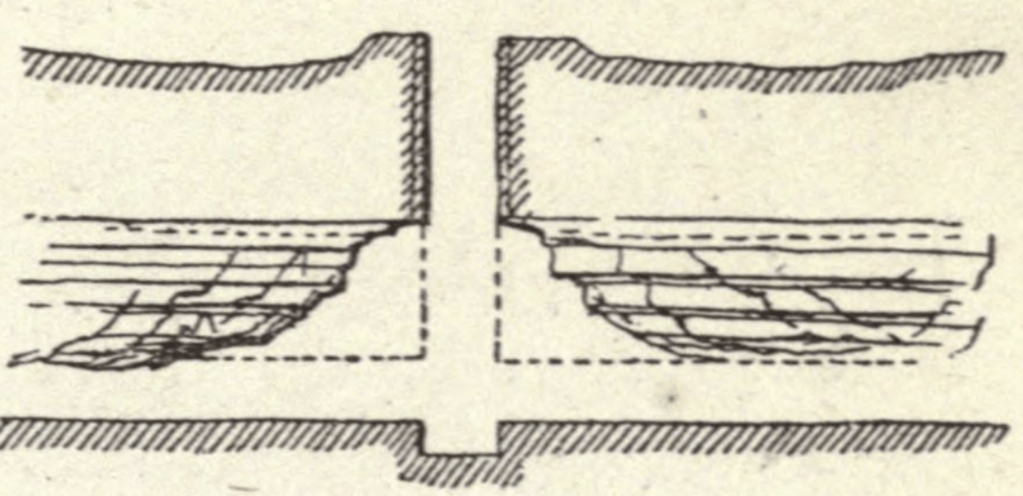

These early operations were limited by technology and geology, as Lancashire’s coal seams were often deep and gassy, posing risks, but they were the bedrock that the foundations of the industrial revolution were built upon.

The Industrial Revolution in Lancashire

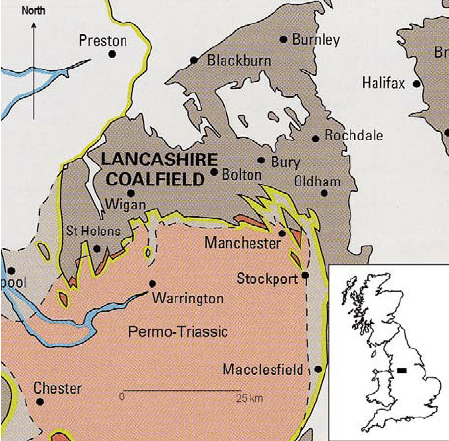

Lancashire’s true coal boom coincided with the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries. The county’s vast coalfield, part of the larger Lancashire and Cheshire field, provided abundant, accessible fuel to power steam engines, Cotton mills, ironworks, and canals.

Key innovations emerged here: Lancashire was at the forefront of mining advancements, including early use of steam engines for pumping water from pits and the construction of Britain’s first major canals (like the Bridgewater Canal in the 1760s) to transport coal efficiently from mines to markets in Manchester and beyond.

The coalfield’s productivity soared and by the late 19th century, hundreds of collieries operated across the region, from Wigan and Leigh in the west to St Helens, Chorley, and Burnley in the east and north. In 1880, mine inspectors recorded around 534 coal pits in the Lancashire field. Production peaked around 1907, when 358 collieries yielded more than 26 million tons of coal annually, powering not just local textile mills but Britain’s growing empire and global trade.

Major collieries included Astley Green (opened in 1908, a symbol of late-era deep mining), Parkside in Newton-le-Willows (sunk in the 1950s-60s and the last deep mine on the field), and countless others in urban and rural settings.

Wigan itself earned the nickname “capital of the Lancashire coalfield” as, at its peak, over 1,000 pit shafts lay within a 5 mile radius of the town centre.

Consolidation, Competition and Decline

Nationalisation in 1947 brought the industry under the National Coal Board (NCB), consolidating operations. At that point, only 108 collieries remained in Lancashire (down from hundreds pre-war due to exhaustion of shallower seams and mergers of others).

The post-war era saw rapid decline. Geological challenges, competition from cheaper imports, shifts to oil and gas, and mechanisation reduced the workforce. The 1960s marked aggressive closures, and by 1967, only 21 collieries operated. Many pits closed despite workable reserves, as production targets became unattainable.

The last deep mine, Parkside Colliery (at Newton-le-Willows in the St Helens area), closed in 1993, without exhausting its coal. Smaller or surface operations lingered briefly, but by the early 21st century, deep mining had vanished entirely from Lancashire. Britain’s last deep coal mine (Kellingley in Yorkshire) shut in 2015, and the remaining activity focused on a handful of surface sites elsewhere in Britain.

As of 2025-2026, no active deep or large-scale coal mining occurs in Lancashire, with the national industry reduced to a ghost of its former self by net-zero goals and a planned ban on any new licences.

Lancashire’s Coal Legacy

The Lancashire Coalfield produced hundreds of millions of tons of coal over its lifetime, powering Britain’s industrial might, but at great human and environmental cost.

Frequent and horrific disasters, serious health issues like pneumoconiosis, and scarred landscapes from spoil heaps and subsidence left a lingering legacy that echoes down the generations.

Today, sites like the preserved Astley Green Colliery (now the Lancashire Mining Museum) stand as poignant reminders, with headgear and engines preserved for education and tourism. Reclamation has transformed many former pit sites into parks, nature reserves, and housing.

Communities once defined by mining have diversified, though the industry’s social impact, strong union traditions, community resilience, and economic challenges, persist.

In the next part of this series I’ll look at one of these communities and how it recovered from one of the last major mining disasters in Britain.

Collier Lass (anon)

My names Polly Parker, I’m come o’er from Worsley,

my father and mother work in the coal mine:

Our family’s large, we have got seven children,

so I am obliged to work in a mine.

And as this is my fortune, I know you’ll feel sorry,

that in such employment my days they should pass;

But I keep up my spirits, I sing and look merry,

although I am nought but a collier lass.

By the greatest of danger, each day I’m surrounded,

I hang in the air by a rope or a chain.

The mine may fall in, I may be killed or wounded,

may perish by damp* or the fire of a train.

And what would you do were it not for our labour,

in wretched starvation your days you would pass.

While we could provide you with life’s greatest blessings,

Oh do not despise the poor collier lass.

All the day long you may see we are buried,

deprived of the light and the warmth of the sun,

and often at night from our beds we are hurried,

the water is in, and barefoot we run.

Although we are ragged and black are our faces,

as kind and as free as the best we are found;

Our hearts are as white as your lords in high places,

although we’re poor colliers that work under ground.

I am growing up fast, and somehow or other,

there’s a collier lad strangely runs in my mind.

And in spite of the talking of father and mother,

I think I should marry if he was inclin’d;

But should he prove surly and will not befriend me,

perhaps a better chance will come to pass,

and my heart I know, will to him recommend me,

And I will no longer be a collier lass.

* ‘damp’ refers to firedamp, an explosive mix of methane and air that can build up in poorly ventilated mines

More women were employed in the coal industry than any other in Lancashire until a 1842 act banned women from working underground.

If you enjoyed this you can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee, every contribution will go towards researching and writing future articles,

Thank-you for visiting,

Alex Burton-Hargreaves

(Feb 2026)

Such a harsh and thankless life, I learned more about the industry and its many, many victims when living in S. Wales. 😦

Good article Alex

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, it was a very hard life, and it makes you very grateful for how we live now

LikeLiked by 1 person